The Oneirocritic

When I read about Patroclus’s ghost in the Iliad (Book XXIII), I immediately thought that Achilles must have been dreaming under the spell of emotion. Yet one detail from that encounter screwed itself into my memory: Patroclus’s ghost is depicted as a smoke that vanishes, “with a faint whirring sound.” It makes no vulgar noise—nothing like a piano struck by accident or a lid slammed firmly over a boiling pot. Instead, it produces a cricket’s song, the sound of sand running through an hourglass. And this, perhaps, is the sound of the other world, the language of dreams. A whirring like that of an old clock.

With this information aboard, I came across a note about Cirtă the oneirocritic. This man, whom I want to tell you about today, was well traveled and seasoned by life. He had beaten the roads to Stambul and to Vienna, where he had bought himself a tall hat, like a princely potcap. He had read a thing or two in his lifetime—among them ancient and medieval treatises, including the Greek Artemidoros’s manual of dreams. Not to mention that he made a habit of jotting down things he heard from sorcerers and from the symbologists of the eighteenth century, who, just like today, were fellows ready to daze you, to toss you into all sorts of pits dug into the asphalt of words.

You have surely met people who see a number—say, a gate number—and from it spin an entire story of obstacles and predictions, often catastrophic. It was much the same back then, and Cirtă had noted such things so thoroughly that he could answer any question you put to him.

When a man dreamed something that continued to weigh on him for more than an hour, he would slip on his slippers and knock on Cirtă’s door.

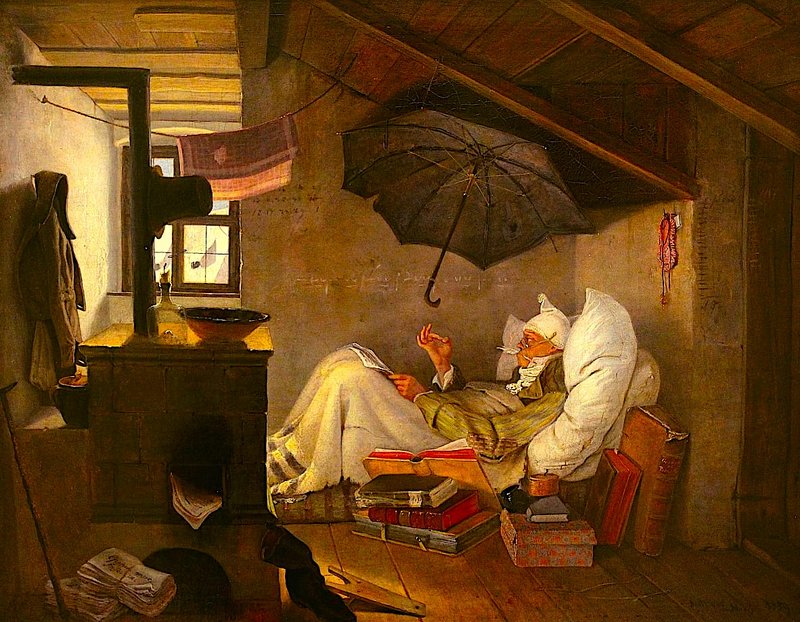

Cirtă lived in an attic overlooking the Dâmbovița, a cramped little room, but fitted with a table at which the visitor was invited to sit.

To begin with, the visitor would drop a coin into the tin bowl and wait to be invited to tell the dream. If the dream was simple, Cirtă was an honest man and asked for no more money. But if it was something complicated, he would ask for a bit more—sometimes a pará, other times as much as a taler. For instance, if you dreamed that your mother appeared to you, though in reality she had long been dead—you needed no interpretation. Everyone knew it meant a small trouble was looming, nothing of real importance.

In dreams, the dead do not linger in conversation unless something serious is at stake.

When they merely pass through, as if belonging to another reality, there is no reason for concern.

Just as harmless were dreams in which you flew—always a good sign—dreams of clear waters, of flowers, and so on. Among the complicated dreams were those with messages, with letters or books. These were intellectual dreams, demanding deep analysis.

One day, a neighborhood market woman came to Cirtă—a woman without schooling, who sold garlic, caraway, and other local spices, hauling them daily to the market.

Her dream was indeed full of mouths that spoke incessantly. She had dreamed of a kind of gathering of sages who declared that the history of the world had come to an end. Morals were in ruins, scoundrels roamed in packs, and idiots decided the fate of the majority, which, as usual, fumed in silence.

And among the words of the great sages, the market woman remembered only one sentence, which she repeated from home all the way to Cirtă’s place, for fear of forgetting it:

“When you hear a long whirring sound around Colțea, know that these are the souls of the dead, come from the other world.”

Cirtă asked for another coin and some time to think. The dream troubled him; it was complicated.

Not after one hour, nor after two, nor even by the end of the day did he find an answer. So, acknowledging his limits, he went to return the money to his client.

The market woman lived in a somewhat larger enclosure, with curtains that made you feel as though you were inside a glass of Cotnari wine. A place made for dreaming and for rushing off to sell spices.

At first they spoke about the dream, trying to make sense of those souls from Colțea. And because they were talking about dreams and sleep, Cirtă fell asleep in that room of watery light and unspoken promises.

In the days that followed, it seemed natural to him to visit the market woman again.

After all, it was her dream—she had planted it in his mind, along with that whirring from the other world. So he spent another night with her. And another.

But the next time he tried, the door was closed. The woman went on with her vegetables and baskets of spices—and after about a week, she forgot the dream and Cirtă altogether.

The oneirocritic, however, was increasingly undone, more and more convinced that the garlic seller’s dream contained the future of the entire world. And with whom could he speak about such a dream, if not with its author herself?

He went to Colțea, counted the steps, examined the columns, and stood with his ear pressed inside the nave. He needed a sign, a confirmation of his suspicions. The woman had not come to him by chance: this mystical message was meant for him. And now, instead of telling him more, the dreamer had shut the door, disappearing forever! It was unjust.

One morning Cirtă woke with a ringing in his ears. It was long and oppressive, like a cord drawn through the eardrum, like a silver thread adorned with fine wires. At times he heard a dying bull’s bellow; at others, millions of crickets burrowed into his ear.

His quiet life, as a great interpreter of the god Oneiros, was over. The market woman had dreamed especially for him.

He was convinced that this sound was the whirring from the other world, the undeciphered language of ghosts.

And since a message exists for the one who believes in it, the oneirocritic took up a quill and began to transcribe the long story of souls escaped from death.

His book— in which, of course, the market woman plays a significant role—remained one of the most convoluted writings, periodically igniting yet another mind like his own. At the end of the book is written the date of the general end: a day in April, when a long whirring will be heard from Colțea.

One question alone haunts me, if you will allow it: what, after all, was whirring in Homer’s reality—or, rather, in that of his character, Achilles?