Litera MOV is a project launched together with the National Museum of Romanian Literature in 2020 and carried out until 2024. It began as an aspiration shared by a small elite of dreamers—a personal game in which I fictionalized real events, extraordinary or mundane, drawn from the forgotten history of eighteenth-century Romania: wills, letters, shopping lists, court records, complaints, bills of sale, and other domestic documents.

I wrote some of them; others I told orally, in front of the camera—not necessarily in that order.

Some of these stories were filmed at the Museum of Literature, at the Filipescu-Cesianu House, or at the Central University Library (BCU). The videos were posted on various platforms, including on my YouTube channel, where you can find them in chronological order.

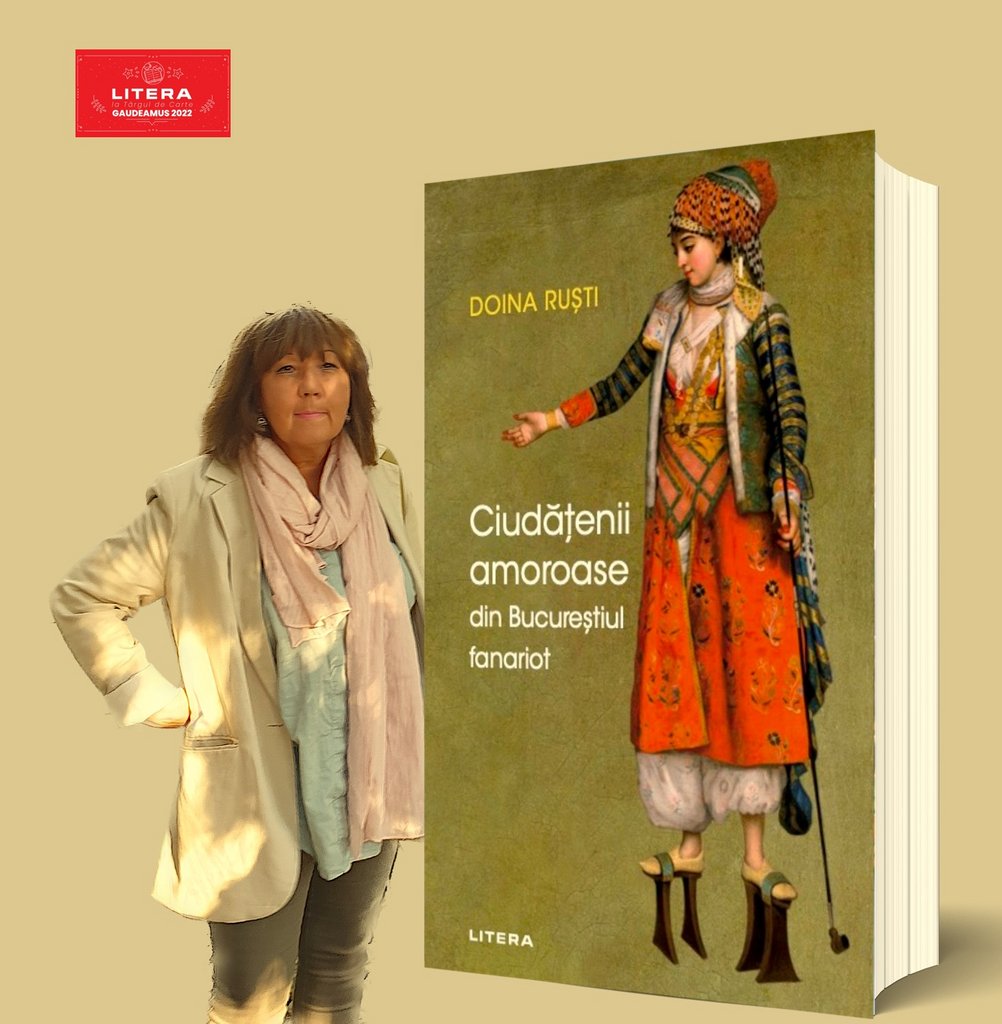

The written stories appeared on my blog at Adevărul or directly on my personal website. In time, hundreds of texts accumulated; one hundred of them were published in two bestselling volumes: Amorous Oddities from Phanariot Bucharest and The Depraved Man from Gorgani.

The rest remained virtual—scattered across time, places, and worlds.

I have now decided to arrange them thematically and to turn everything into a fictional hub of the Phanariot Era, a personal map of the eighteenth century. Why? So we can play together. So we can drink our coffee among velvets and silks. Perhaps you’re interested in a theme—love stories, adventures, mysteries, and many others. If you click on a theme, you’ll find the stories that belong to it.

Let me also tell you where the name Litera MOV comes from. It goes back a long time: when I was learning to write, I drew a purple letter in Homer’s Odyssey. Later, this barbaric act saddened me; yet beyond that awkward mark, the adventure was beginning. And that monstrous letter became a gate through which I still walk today: the purple gate.

Would you like to come in as well?

It was a rare fruit, which Popp managed to procure with difficulty, already packed for a long journey. Apparently, no one ordered more than one piece, which arrived sealed in a polished wooden box, painted, with a hinged lid. The pineapple was laid carefully in straw, and the little crate was sealed with a black padlock bearing the inscription Keller.

Read the full story here (ro).

The dyer woman from Pitar Moș—a rather select area even then—enjoyed a certain prestige due entirely to her dye workshop, one of the largest in Bucharest, spread over almost 3,000 square meters: a courtyard with vats, great iron tripods, a drying room, plus a laboratory where she prepared pigments. She was an artist, attentive to shades, materials, combinations.

Full text here.(ro)

The Umbrella from His Dream

A prelude to the story, with Bogdan Simion Cobzarul and Lăutarii de mătase.

Everything began behind the Church of St. Sava, where there was then a patch of weeds, the remnant of an old cemetery. A few ancient stone crosses could still be seen. There, under a wild blueberry bush, the immortal life of Elina, the ișlicăreasă, began.

Married only a few months, this woman—who through her deeds would soon sketch a map of rare pleasures—made daily trips through the city, for her husband was a renowned maker of ișlice, so passionate about his craft that every cap leaving his hands was a masterpiece, an object of wonder. He crafted globular ișlice from broadcloth, in every color, but also from fine leather richly dyed, from heavy silk, even from hemp softened with a thread of mulberry silk. He had an excellent mold, a balloon-shaped form on which he stretched any material to perfection.

When the caps were ready, Elina loaded the carriage with those monumental ișlice and delivered them to customers, collecting payment with an infinite delight—especially silver coins, but also talers or second-hand parale: all good money, tucked according to value into small cotton or leather pouches, or simply slipped into her skirts and bodice.

But this perfect life had a crack.

One day, Elina had to deliver a special order to St. Sava, for a schoolmaster. To shorten her route, she stopped the carriage near the church and, dragging the basket in which a splendid ișlic sat enthroned, cut across the overgrown lot. And somehow, under the sun of a day where tails and temptations mixed freely—perhaps under the impulse of a fairy’s fingertip—Elina found herself face to face with a man.

He was dressed in silk, a figure fallen from the sky; and to reinforce this impression, he began speaking in a mysterious language. Elina froze, staring at the stranger’s lips as they uttered strange, unearthly sounds. Then the man pulled out a notebook and began to draw. His hair, tied in a cue, had slipped behind his ear, and his eyes shone like a predator’s under the shade of a slightly drooping fez.

Elina stood for a while, but when the man gestured to her, she approached without a trace of shyness. On the white page, he had sketched her portrait exactly as she stood, one hand on the basket. There was something unworldly about the entire encounter. The tall mallows, the hemlock, the tangled bushes made the whole scene feel detached from real life.

The rest happened spontaneously, almost mystically: a swift joining beneath the blueberry branches. A few mallows snapped, the man’s fez rolled to the fence, and Elina lost a tassel from her shoe.

When she stepped out of the churchyard, she was another being, and the encounter had ascended to the heavens among the deeds that never die.

A few days later, she stopped to buy thread from a peddler. The man told her that he kept more goods at Chiriță’s Inn, where he also lived, and Elina offered to accompany him. The haberdasher was shocked, but sensed it wasn’t his place to judge her.

The room at the inn was like an eye over which a fragile eyelid trembled. Through the barred windows, the crowns of linden trees swayed, and on the bed the shadows of subtle beings shifted lazily. What had begun as a small transaction became a passionate entanglement. The floor was carpeted with Elina’s many skirts, and the man’s șalvari ended up on the windowsill. Nothing she had ever experienced compared to that afternoon, presided over by a faun. The seller of needles and thread melted within an hour, and in his new state—milk and honey—he slipped slowly under her skin, spreading through the vast territories of her fevered flesh.

The next day, Elina was seized by panic, tormented by questions of duty and guilt. In this state she walked onto Barbers’ Lane to deliver some ișlice. But after finishing her work, on her way back to the carriage pulled aside in the shade, she noticed someone watching her.

A man leaned against a wall—a bug-eyed, rather scrawny type. She intended to ignore him, but on his lips there flickered a melody, whispered like wind. She glanced again, and the man—who now she could see held a silver-headed cane—beckoned her. He hadn’t spoken; he was surely a good-for-nothing, yet Elina’s feet seemed bound to him. With small steps that, at first glance, suggested hesitation—but which were in truth besieged by emotion—Elina reached a doorway. From the balcony hung a curtain of honeysuckle, and from the garden came the cry of an angry cuckoo.

Elina lingered for many hours in the stranger’s house. The curtains were drawn, and in the dim light the man seemed made of tobacco smoke. Later, in the many nights that followed, she no longer remembered his features. She never doubted that the man in the house of honeysuckle vanished together with her desires.

From that day on, the city changed its geography for Elina. From the teeming crowds, the piles of houses and the uncountable streets, only three places remained—those that mattered. Although she met other men, none ever again had the privilege of entering the secret map. In the sweet world of pleasure and abandon, life continued to pulse at St. Sava, at Chiriță’s Inn, and on the immortal Barbers’ Lane.

The Map of Happenings

by Doina Ruști

(from Amorous Oddities from Phanariot Bucharest, Litera, 2022)

We are in the spring of 1793, under Metropolitan Filaret, shortly before he fell into the disgrace of Prince Moruzi. Into the chancery of the Metropolis walks a man named Arghir, asking Filaret to release him from the marriage in which he had been chained for many years.

Arghir appears to be a determined man, the kind one does not need to question much. Even so, a reason had to be stated and written in the documents for posterity. And this reason had no semantic veil whatsoever: Arghir confesses that he can no longer bear his wife, Manda.

It is not a matter of adultery. The man does not want another woman. He simply fears that if he continues living under the same roof with Manda, there will be bloodshed. In fact, it is more than that: he does not wish to be married at all; he no longer accepts being a husband to a wife.

Each day unfolds the same. He wakes up and sees Manda. A red vapor settles gently over things, a poison that slithers treacherously around the divan, under the sheets, over the shelves with little objects, coiling around the bottles on the rack, slipping under the door and bursting into the kitchen—until everything, from the slice of bread to the cream in the pot, becomes red, with a bitter taste like the blossom of the sour cherry.

And in his mornings—each one red—Arghir rises from the bed and tells Manda, word for word, all the bitter insults that his vocabulary has collected in a lifetime. She is the mole, the viper, the dirt on the shirt, the piece of meat turning rotten, the strip of land behind the house where men relieve themselves night after night. Manda is the leprosy crusted upon the face of the day, the boil rising on one’s cheek.

But even after he speaks all the words—those words said to have the power to change the world—Manda is still there, in front of him. He grabs the whip and lashes her, which brings a small victory: Manda runs, hides under the table, and he is forced to take the fire iron to pull her out. At last he pushes her toward the door, throws whatever he can find at her, and with the help of his cane, his fist, and his boots, finally drives her into the courtyard.

The neighborhood gathers at the fence, and it takes Arghir nearly an hour to force her through the gate.

But he barely has time to drink his coffee before Manda—the same one, bloodied, with her lip split—walks right back through the door.

Days follow one another, and Arghir fights an unrelenting battle. He has tried every blunt and sharp weapon, from whip to knife to cleaver, but Manda refuses to leave; she will not be moved from the house.

Arghir filed a complaint at the Metropolis, and after examining the situation, Filaret declared them divorced.

But Manda sent a letter directly to Moruzi, claiming she had no husband to forsake: once bound by Christian vows, it was clear that only death could separate them. As usual, Moruzi was swayed by her Christian arguments and issued an order for Manda to return home.

All Arghir could do was write his novel. As if telling the story of his misery would interest anyone! He insists he does not write out of vanity, but because he wishes with all his heart that his future acts be laid squarely at the feet of the prince, who forces him to endure Manda. It is a written warning, meant to clarify the truth; a novel calling for the solidarity of his fellow men—at least the men—but more than anything, an indictment of the true culprit.

Thus he writes, in black and white, that he intends to strangle Manda with his bare hands, until he sees her tongue protrude, her face turn purple, and her spirit— that red vapor coiled within her blood—depart from her body. Immediately afterward, he will hang himself in the porch, so that everyone may see and understand what a man who no longer wishes to be married is capable of doing.

With this detailed confession—his “novel,” as every man seems to write nowadays—describing meticulously each phase, object, and small detail, he presents himself in Filaret’s office, leaving the Metropolitan speechless.

Today, it would have been considered the announcement of a crime, a document that would land him behind bars. But then, in 1793, Filaret sent a letter to the Palace, summarizing in a few lines the intentions of a determined man, and the prince—who until then had sided with Manda—cast her out of her privileged role and sent her away.

What strikes me as strange is that not long after this episode came the rupture between Moruzi and Filaret. The latter spent the final part of his life in a monastery, where, believe me, it was cold and desolate—and the only comfort of the exiled former metropolitan was the memory of a red vapor.

(translated from Doina Ruști – Amorous Oddities from Phanariot Bucharest, Litera, 2022)

Manda

TVR

A shrub with black, fragrant wood, called calembec, stands at the very origin of handwriting. Today, this wood is used to make beads, prayer ropes, small boxes, and other delicate objects — among them, writing handles. Does anyone still remember what a dip pen looks like? A quill holder? A slender stylus, the ancestor of the fountain pen, adorned with carvings, velvet caps, or silver fittings. These were worn at the belt, attached with chains and cords.

Often they were made from the black wood of the calembec, and at one end was fitted the nib, cut from a goose feather. The object was also called calamos, from Greek.

But calembec was also used in making ink — hence the word călimară (from Greek kalamari), the glass or metal container in which ink was once kept. Naturally, there was also a writing kit, a calamarion, consisting of pen-holder, inkwell, and paper.

Under these conditions, all places where writing was done — chanceries, accounting offices, tax collection bureaus — were called calemuri, and the clerk whose main occupation was writing was a calemgiu, or diac (scribe).

Preoccupied with writing and especially with the instruments of writing, Tilu Băjescu also prepared inks — including one rather amusing: invisible at first glance.

So bitter at life, and half-stupefied after spending so long shut up indoors, he took a job as a scribe. And in every document he left messages, additions, confessions. Though he generally drafted wills, contracts, bills of sale — and occasionally letters — he managed to slip his own history between the lines. It was his only pleasure. And he was not the only one devoted to such debauchery.

Everything that crossed his mind found its way into the texts he wrote: forbidden couplings, descriptions of lascivious attitudes, licentious words, small perverse gestures, even notes about objects of pleasure or anatomy hidden beneath clothing — in short, everything that sustains natural curiosity and the appetite for life lay inscribed in those papers.

If, for instance, he had to write a contract in which two people reached some sort of agreement, he took care to add a word here and there, a shortened curse, to draw in place of a tilde a sinuous figure, or instead of an accent to let slip an obscene club, or, in place of a signature, a long word in Latin. He was obscene, yes — but discreetly so, to the point that no one but he knew what he had hidden there.

The papers multiplied, and Tilu’s life grew labyrinthine, and this began to show on his face. His experience as a cryptic calemgiu had placed a sly gleam in his eyes, narrowed slightly, like two windows of an immense chamber. And as the signs on the paper multiplied, the chamber in his mind expanded, a hall with rooms in which his deeds took shape. Men and women entwined on floors, divans draped with nudes, drunkards and hookah-smokers, orgies and feasts — all unfurled exactly as on paper, orderly rows of acts, always forming a cluster that reached the gate.

And the territory grew with each page, becoming in the end a fortress with twelve gates, an abraxas, like the year, like the universe. Numerology mattered to Tilu, and once he became master of a fortress with twelve gates, he stopped — plunging his eyes deep into the tar-like ink.

That is how I discovered him, and made him a character in The Phanariot Manuscript.

For many, happiness means recording every act of their life, from bath gel to the books they have read or not read, the pavement in front of the house, and especially detailed impressions of friends, colleagues, and enemies.

Instead of that, Tilu, more honest I’d say, noted down his small impurities between the lines of official documents. Not because he was ill, but because of the calembec pen — narcotic, soaked in a liquor of crickets.

Calembec

}}