Every time April 1st approaches, I find myself thinking of Nicolae Mavrocordat, whom the people of Bucharest once famously fooled, in keeping with tradition. It was the year 1716, and Mavrocordat was thirty-six years old. A cultivated man with a vivid imagination, he was already preparing The Leisure Hours of Philotheus, his refined philosophical work, translated into Romanian only in 2015 by Claudiu Sfirschi Lăudat.

What history records—and what I have mentioned before—is that on the morning of April 1st of that year, his very first year as ruler in Bucharest, Mavrocordat was tricked into believing that the Germans had entered the city. Terrified, he gathered his family, climbed into a carriage, and fled toward Giurgiu.

But what would history be without details—without those touches that make it vivid and believable?

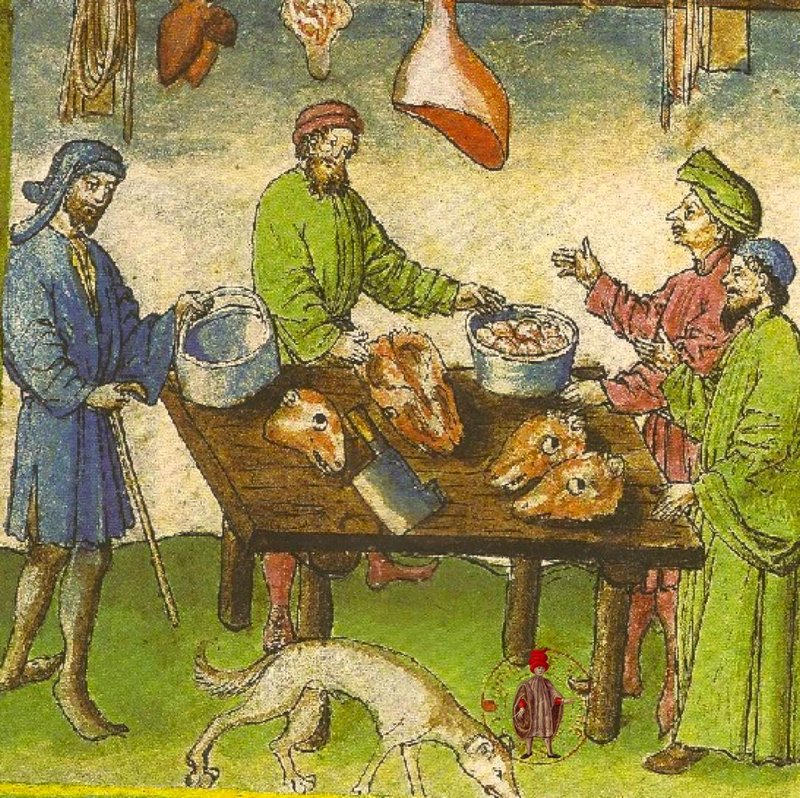

That morning, the young ruler woke up and asked for crayfish fritters, a dish he had announced the day before. It was a highly prized meal, included in Brâncoveanu’s recipe book. River crayfish were boiled, shelled, finely chopped, and mixed with vegetables, herbs, ground almonds, breadcrumbs, eggs, and garlic. The mixture was shaped into fritters, fried, and served hot, accompanied by a small bowl of rose vinegar—prepared in advance, diluted with water, sweetened with honey, and flavored with hot peppers and mint leaves.

But on that April morning, when the ruler requested breakfast, someone had forgotten to buy crayfish.

The palace staff panicked. Mavrocordat waited at the table, book in hand, wrapped in a silk robe. In the kitchens, despair reigned. The steward turned pale; the fisherman was ready to disappear altogether. Just when all seemed lost, the cook remembered that her brother, who owned an inn, had surely prepared crayfish fritters. The problem was that the inn lay far away, on the road to Giurgiu. Fetching the food would take too long, and the ruler would lose his temper.

After a brief council, the servants decided to take Mavrocordat out for a walk. But how? Ideas flew from one window to another until, by sheer chance, they collided with the spirit of April 1st. Thus the story of the Germans was born. The servants began shouting through the palace, stirring up chaos in the courtyard. Some ran into the street, screaming wildly, drawing in eager lovers of scandal.

By then, among the crowd gathered at the gates, word was already spreading that it was all a prank.

Mavrocordat, however, was genuinely frightened. One can easily picture his gentle face, his blue eyes fixed on the palace gate. Still in his robe and house slippers, he grabbed his children, jumped into a hastily prepared carriage, and the coachman whipped the horses toward Giurgiu.

Regretfully, he thought of what he had left behind.

Before long, the carriage stopped. The Mavrocordats were invited into a roadside inn—a modest house on the outside, but unforgettable within. The sincere smiles and deep bows encouraged them to enter.

They crossed several rooms and were led into an inner courtyard covered with glass panels and grapevines. It was an extraordinarily pleasant place, full of flowers and birds, but its true marvel was a basin with several fountains—“gutters through which water sprang in spirals,” as Mavrocordat himself would later write in The Leisure Hours of Philotheus.

The cook’s brother was no ordinary innkeeper; he was, after all, kin to the palace cook—and a hardworking man with a love for beauty.

Seated on divans among silk cushions, the Mavrocordats tasted crayfish fritters prepared in the Wallachian style, forgetting entirely that they were being pursued, that they were supposedly in danger.

They had barely had time to form an opinion about the dish when the servants arrived to explain the April Fool’s custom.

Nicolae Mavrocordat was a gentle, educated ruler. He understood the tradition and even accepted that he had been fooled out of affection. Still, in the weeks that followed, he dismissed the deceitful servants. The beautiful roadside place also vanished: the inn’s cooks were brought to the palace, and the owner labored to build a glass-roofed pavilion for the ruler’s meals.

I should add that throughout the eighteenth century, glass was highly prized. Another Phanariot ruler even built a bridge with glass walls, and pavilions were all the fashion. A particular turquoise glass was especially sought after, produced only in Târgoviște, where perfume vials were also made.

Despite the fact that some people lost their positions, April Fool’s Day survived. As for crayfish fritters—my grandmother used to prepare them with a passion I never inherited.