Because we are in the season of eggs, let me tell you a story about three people and their dreams—unwittingly bound together by an unusual dessert recorded in an old recipe book.

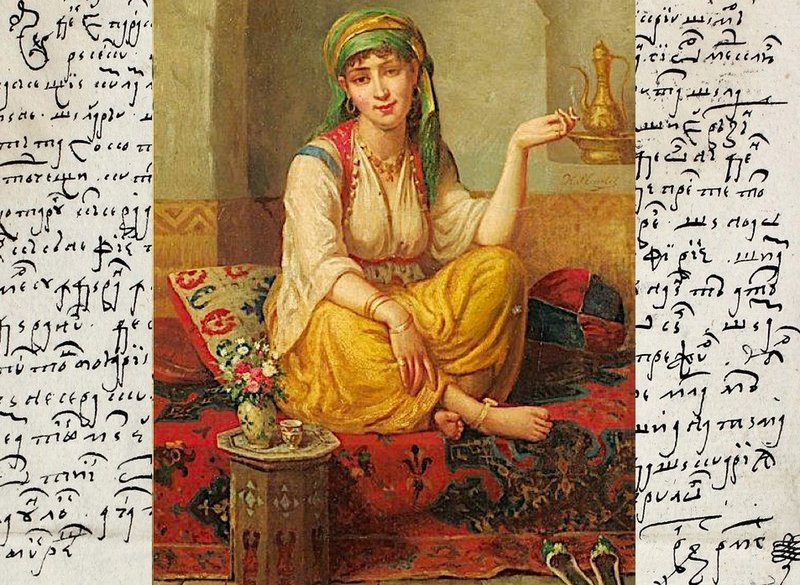

Passionate and tireless, he had made a name for himself in Bucharest with his remarkable bracelets—most of them silver, but also fashioned from humbler materials: copper, tin, beads, woven wire, silk adorned with tiny metal studs.

His dream was to open a shop in the very center of the city.

He worked relentlessly, and on Sundays he would take his family by carriage down to the Dâmbovița, to a famous fair known for its sweets and cheap German watches—trinkets that rarely worked, but could be worn as ornaments, hanging from a gilded chain pinned to a shawl.

Among all his pleasures, none ranked higher than sweet little eggs—a sought-after dessert sold in the streets, in markets and fairs. Hard-boiled eggs were sliced lengthwise, the yolks removed and mixed with other ingredients (butter, lemon, ground walnuts, blueberries or other seasonal fruits) into a sweet-and-tart cream, which was then piped back into the egg whites. Each little “egg” was coated in almond fondant or sherbet and topped with a single jewel-like garnish—a grape, raisin, pistachio, cherry, or at least a mulberry. Arranged on a tray, they were sold individually, and every Sunday the jeweler bought one.

That was how his fortune began.

As he followed the tray with a trained jeweler’s eye, he spotted a treasure: at the crown of one of the eggs, a ruby was gleaming.

He bought it, and soon fashioned a bracelet that would enter the history of Bucharest—an intricate braid of golden wires, adorned with the gemstone taken from the dessert. To make an impression, he displayed it in a luxurious shop window at Hanul Zlătari, where the city’s most fashionable businesses were located. Two weeks later, the bracelet was purchased by Venețiana Văcărescu for the exorbitant sum of 2,500 talers—money that allowed the jeweler to rise gracefully out of his mediocre life.

He opened his long-dreamed-of central shop and began designing ever more refined, ever more expensive pieces.

Yet throughout all this success, a faint question persisted among his important thoughts: what had a ruby been doing inside the cream of a sweet egg? Who had put it there? Could the girl who sold the eggs have been a witch?

Since she often came to the fair with her tray, the jeweler began to watch her, then speak to her, quickly realizing that she knew nothing about the ruby. How, then, had it ended up there? Perhaps it had fallen from someone’s pocket among the cherries. In any case, it had been a godsend. The jeweler dropped some coins into the alms box at Zlătari and gifted the girl a ring set with a glass stone.

The seller of sweet eggs was a soap-maker from Oțetari. On Sundays she ran to the fair with her tray, supplementing her income. She was saving money for a ring she had seen at a cornmeal vendor’s stall—a charming piece of greened tin, ennobled by a small jasper-like stone.

That was her dream.

One Sunday she noticed a jeweler watching her. She knew him—he had become famous throughout the city after selling a bracelet with a ruby bead. It seemed to her that he looked at her in a certain way, like a man begging without words. But only the next day, when she saw him again wandering through Oțetari, did she become convinced that he had designs on her.

Lately, she felt she was in demand. A small cosmetics merchant had also appeared, lingering nearby, supposedly interested in her soap—an obvious pretext. She knew very well that her soap had no market value; otherwise she wouldn’t have had to sell sweet eggs at the fair. She made wormwood soap, good for laundry and rugs. She knew nothing more—she had never managed to coax fragrance from it. Yet this merchant produced a bottle of perfume and told her he had brought it especially for her, to help her understand what kind of soap she should be making, which scents were desirable. He asked about her dowry. It was clear he was inquiring seriously, and she confessed that unfortunately, apart from soap, she owned nothing.

One day they both appeared—the jeweler and the merchant—standing at a distance from each other. She went on selling her soap, pretending to gaze across the water, at the white sails.

That same evening, the jeweler returned with a small pouch of cotton fiber.

“Take it,” he said. “Take care of yourself.”

And she knew she would never see him again—because that is what such words mean: you are on your own now.

She was right. She never saw him again. Inside the little pouch was a thin ring, a simple silver band with a shard attached, no larger than a millet grain.

The soap-maker sold it to the cornmeal vendor, who in exchange gave her the ring she had dreamed of, along with a pair of shoes that broke the first time she wore them.

Around the same time, the perfume merchant disappeared as well.

He was no merchant at all, but a seasoned thief—a pickpocket respected in his trade for his light hand. There was no anteriu whose pockets and hidden seams he couldn’t spot from afar. He worked alone, using a gaze impossible to avoid: green eyes, a certain warmth that melted you into jelly. And then there was his hand—peerless, like the tail of an old cat. He stole rings, bracelets, small objects, but sometimes he entered churches and, while praying, calmly removed a stone or a gilded foil from an icon.

That was how he came upon the ruby. When he saw it, he could hardly believe his luck. The icon’s frame was studded with glass stones—a small sapphire cracked on one side, several jaspers—and among them, unmistakably, the ruby, placed there by someone who had not known its worth. It was a large stone, the size of a cherry plum, perfectly rounded and clear, like the first drop of blood after you cut yourself.

His dream was to pull off a coup like this, to pay for his journey to Istanbul.

Everything went smoothly until the exit, when a ruffian who bore him no love began shouting and pointing. The man had no idea of the stone’s value—he simply wanted to put him in his place.

His misfortune was a captain of the city guard who happened to be nearby; his luck was a tray of sweet eggs.

The rest you know. Not quite everything: in a document dated April 1771, the Văcărescu family reported the theft of the famous bracelet in which a ruby once slept peacefully.