In 1796 there lived in Bucharest a woman known as the Captain’s Widow. Widowed early, she had earned a reputation for being formidable—quick to file complaints, fearless in confronting anyone who crossed her path. The more imposing and sharp-tongued she was, the more natantoala her daughter proved to be.

The girl was careless with details, incapable of maintaining her social standing, and inclined to pay attention to anyone at all—traits that eventually earned her the nickname Natantoala, despite her perfectly respectable name, Ioana. In a moment of Christian indulgence, even the metropolitan referred to her as Ionica, perhaps to underline the innocence that lay, at the very bottom, beneath her natantoală nature.

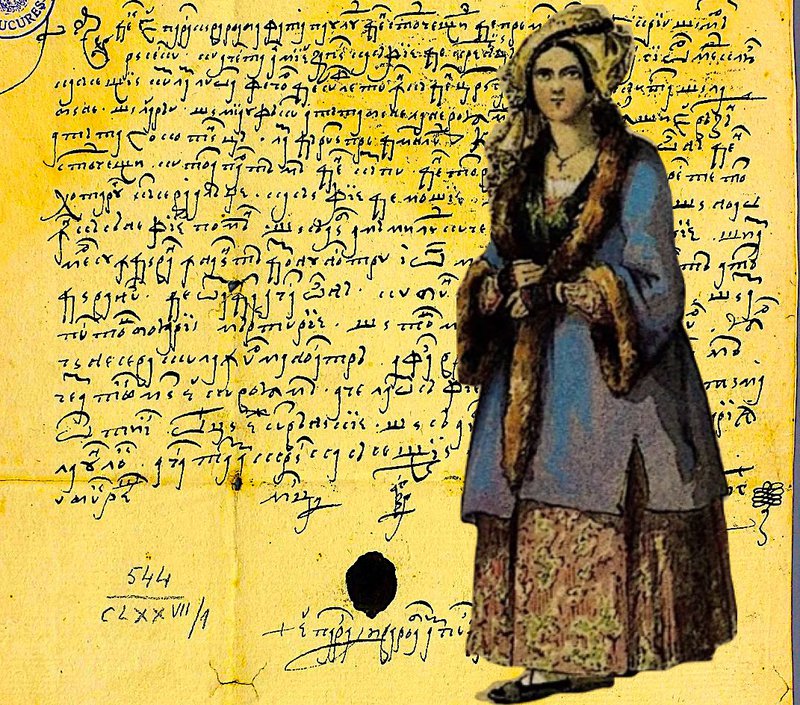

To make a long story short, the girl became entangled with Vlad, a junior clerk with an arrogant air, who—through sweet talk, as the Captain’s Widow later wrote in her petition—stole her maidenhood. A trial followed.

Ionica uttered not a word. The Captain’s Widow raged. The clerk Vlad declared that he would not marry the girl because she was a natantoala. And he was not alone in this view. The girl was examined, analyzed, weighed. It was true: she inspired no respect whatsoever. This was not merely a matter of clothing, but of posture, bearing, rank. Ionica was gentle, but incapable of self-respect. Slightly slovenly, yes—but the essential reason she bore the label natantoalawas her inability to refuse anyone. Excessive kindness, unconditional compliance—these invite trampling. That is how one becomes a natantol: without value, without rank, without a spine.

Naturally, people pitied her for having lost her virginity. But even more, they pitied her because she would forever be walked over. In the name of this pity, Ionica was awarded fifty thalers.

Yet respect cannot be bought. It is gained with difficulty and lost instantly. Natantoala earned no esteem—only a thin layer of mercy. She accepted the fifty thalers, murmured a thank you, prompting the clerk to note that the parties reconciled quickly and therefore certified the matter by placing their finger on the document. Even the Captain’s Widow—so stiff-necked and formidable—signed humbly. The record has survived, like others of its kind, published by Urechia.

A parent’s notoriety is never enough. Children who fail to rise to their parents’ stature are never pitied as parents are. Poor Captain’s Widow—what wretched seed she had sown.

Even with the thalers received as compensation for stolen maidenhood, Ionica would remain Natantoala. Her life drifted from one failure to the next, leaving behind in history only the trace of a finger—one that settled for fifty thalers.

But that, too, is a kind of legacy.

She remained in history.