The word țol / țoale entered Romanian slang in the 1980s and enjoyed a period of undeniable glory. Dressed in festive finery meant wearing official clothes, while someone described as înțolit was assumed to have money and connections abroad. You could never say that someone dressed from state-run shops was înțolit—that person was merely a socialist bumpkin. Țoale meant jeans, fitted shirts in solid colors, hoodies, and other fine garments, preferably cashmere in shades of green, paired with platform shoes (troape) or custom-made loafers.

In rural areas, however, the word țoale continued its shabby existence, referring to old things—blankets, mattresses, worn-out linens, and especially rag rugs.

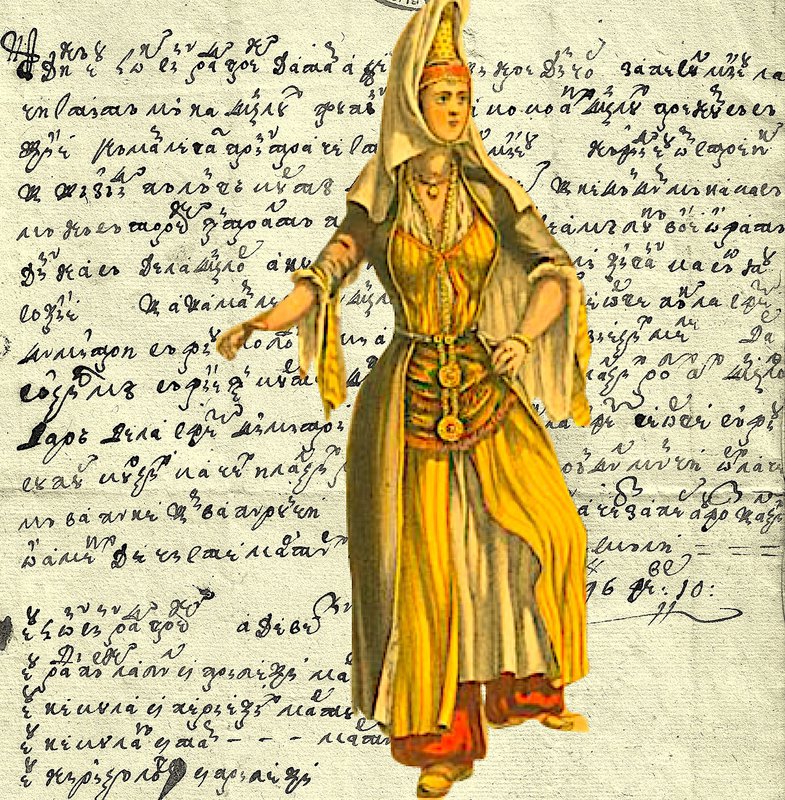

The origins of țoale can be traced back to the Greek tsoli, filtered through the Ottoman Empire and other Balkan cultures.

Throughout history, there have always been dealers in old clothes, recyclers of rags and cast-offs. In my novels, near the Old Princely Court, there is a Rag Market. Sellers of used textiles were known as telari. Few people know that telar, or telal, originally meant a town crier—a vocal messenger who shouted announcements from gate to gate or from Bucharest’s watchtowers. Rag sellers were considered crude people and shouted their wares loudly, so the two occupations gradually merged, until only the stronger one survived in collective memory: the rag dealer.

As proof, I offer the feminine form of telar: teleleică. It did not refer only to a woman selling old clothes, but also to a matchmaker, a go-between, a woman who mediated conflicts or arranged meetings between lovers. From there came her bad reputation: a teleleică was seen as a procuress—useful, but despised.

People are shy; back then perhaps even more so than today. There was no internet, no messages, no social networks through which one could reveal oneself. So they would offer a glass of plum brandy to a bold—or shameless—woman, who would deliver the message in its rawest, most direct form. Free of delicacy, the teleleică did not hesitate to expose secrets, to stir scandal, to make a public spectacle of herself, lifting her skirts over her head. She was, in short, low-born.

That is how the word acquired its harsh meanings, shifting from an honorable role—that of an orator, a person with pure rhetorical vocation—to one denoting foul-mouthed, unscrupulous women.

Such a teleleică lived in Bucharest around the Old Peddlers’ Quarter and roamed the streets as far as Obor, peddling news and smearing reputations. She was tall, cheerful, and fond of brandy.

One day she met a small-time merchant selling headscarves, miserable and utterly alone. The man asked her to soften the heart of a widow from the Pantelimon neighborhood, to make her lower her gaze toward him. In truth, the fellow—who dragged after him a suitcase full of kerchiefs and fine fabrics—wanted to sleep with the widow without making promises, without entangling himself more than necessary. He thought it cool to pay the teleleică—not with money, but with a drink—and then enjoy an hour of pleasure. Before… is always just an hour, because dreams are generous like that.

The teleleică took her mission seriously, set things in motion, and received her brandy.

They walked together for a while, because for many people—especially teleleici—there is little difference between a client and a bosom friend. Even today one says he’s my client, my patient, my professor, as if that placed the other person under one’s thumb. Almost no one sees themselves as subordinate; everyone imagines themselves master of those they have only brushed against. So the teleleică believed she had done the overheated merchant a favor. She sprawled comfortably and made him a shameful proposal, speaking to him with a certain condescension. Wasn’t he in need? Here she was, doing him a kindness, briefly inviting him behind a shack in Făinari.

To her surprise, the man felt offended. He was an honorable fellow. He had once had a small business and had paid fairly. That was her role—and no more. She was not to infest him with lice or other such things.

For the tall, brandy-loving teleleică, eloquent and unbeatable in rhetoric, this refusal from a wretched man she did not respect meant everything.

She stayed indoors for days. As she replayed the events, her self-respect crumbled. It was precisely her unwavering confidence in her own powers that had once brought her success. Rejected. That alone was not catastrophic—but rejected by a man she held in contempt was unbearable. She had reached the edge of her world, and there was no way back.

To be a teleleică and not know it is not so terrible. But to become aware of any fall, however small—that is already a kind of death. You no longer feel like drawing breath.

That is precisely why one must keep clients at a distance.

Teleleică is a Romanian historical and slang term with layered meanings: rag seller, town gossip, matchmaker, and social go-between. Over time, it acquired strongly negative connotations, suggesting vulgarity and moral flexibility. The word is left untranslated to preserve its cultural density.

The Romanian expression “a da pe goarnă” literally means to blow a horn. Idiomatically, it refers to spreading secrets, gossiping, indiscreetly exposing private matters, or acting as a rumor-monger.