Among the many names that recur in eighteenth-century documents is Băjescu (a name I later used in The Phanariot Manuscript). Having grown attached to it, I searched for documents in which it appeared and found several concerning a woman whose first name is never mentioned. She is referred to simply as Băjeasca.

The story begins around 1796 in Bucharest, with a boyar bearing the title of pitar, named Băjescu, from the Băjești family of Argeș. He had a wife, children, and a comfortable life. He was related to the boyar Brezoianu, whose houses stood on what is now Brezoianu Street. Well connected and wealthy, Băjescu lived nearby, moving within select circles.

Sensing his death approaching, the pitar drew up his will, appointing as guardian the vornic Golescu, of the Golescu family. His wife was young, and Băjescu did not believe she could manage the estate. At the time, society generally distrusted widows, which is why they were rarely left in control of property.

After making his will, Băjescu died as promised, and thus began the free life of the young widow Băjeasca—left with children and some wealth, but no supervision. Marriages in those days were usually arranged, mere social alliances, so one might expect the same pattern here. Yet Băjeasca, for the first time in her life, found herself unguarded. A year after the pitar’s death, in 1797, following a period of plague, she began what we would today call a relationship with a certain Ion Apostol, the son of a minor boyar from a Bucharest neighborhood.

What could two people bound by strong passion do for amusement at the time? First of all, Apostol visited her secretly, and there were surely nocturnal feasts, retold by servants the next morning throughout the neighborhood. There were also short journeys—to Ploiești, for instance—fairs (the malls of their time), where one could find everything from tempting foods to sports contests, theater, and dance. Traveling performers roamed the markets: singers, theater troupes, including one led by Théodore Blesiet, composed of three French actors who toured the country. There were popular festivities too: competitions, street processions ending in music and dancing, picnics on Filaret Hill with grilled meats, fiddlers, and wine. Shopping itself was a form of entertainment—orders placed in Brașov or Sibiu reveal an imagination both pragmatic and lavish. Porcelain ranked first: cups, saucers, snuffboxes, seals. Then lapdogs, wigs, fine stockings, German shoes, watches, French wine, exotic fruit. Jewelry and furs were bought locally—diamonds, emeralds, sapphires.

This was the world Băjeasca lived in—and might have lived in comfortably.

But the pitar had many friends who still watched over the reputation of his household. They filed a complaint with the Palace, from which document I learned this story. What were the accusations?

First, the widow was said to have încârdășit herself with Ion Apostol—a word suggesting a public, opportunistic liaison. It was common knowledge that Băjeasca went out with Ion or shut herself indoors with him for days. But worse followed.

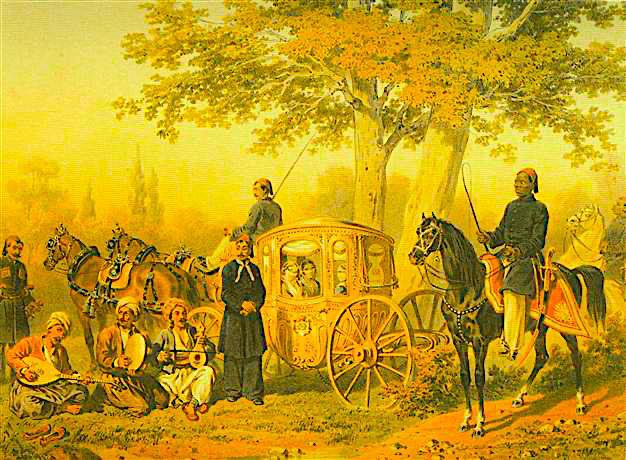

The widow was squandering the estate with Apostol. She had made shameful expenses, diminishing both the inheritance left by the pitar and her own dowry, which should have been preserved for the children. What could she have bought? Carriages, perhaps—fashionable Viennese models with silk canopies and springs that astonished passersby. Or lavish feasts with musicians. Jewelry caught the public eye too: a gold necklace with diamonds in a Lipscani shop window cost a fortune and was guarded by armed mercenaries. Perhaps Băjeasca bought such an ornament—or rings for Apostol. Western women’s fashion crept in: corseted dresses, wigs. In any case, after meeting Apostol, Băjeasca became visibly extravagant.

The ruler read the complaint and demanded an expense list from Golescu, the guardian. Golescu faltered—he had not been vigilant enough.

At first, the spendthrift widow and Apostol were jailed together at the Spătărie for several weeks, even over Easter. While Bucharest celebrated, Băjeasca sighed in a sordid cell. She was charged under a legitimate law: endangering her children’s future.

Brezoianu, as close relative and complainant, took over guardianship of the estate and pledged to care for Băjescu’s children.

The widow’s opinion was never requested. By mid-May, the verdict was delivered: Apostol was released, free to go wherever he wished—after all, he had committed no crime, merely been a convenient partner. Băjeasca, however, was punished harshly and without appeal: exiled to Viforâta Monastery, still standing today, founded by Vlad the Drowned.

Exile meant further humiliation: she was stripped of civilian clothing and her head was shaved.

To end on a less bleak note, I should add that some women sent into monastic exile later petitioned for forgiveness and, if sufficiently diplomatic, managed to return to society—though never to their former rank.