Ioniță Racotă is a man without a word. He made a sacred vow—to marry a girl—but when the time comes, he categorically refuses. The girl’s mother, Calița Călineasca, is outraged and files a complaint with the Metropolitan. The girl has no name. She has no face. Nothing at all is said about her. Sometimes, in documents of this kind, one encounters an unlawful act—rape, sexual deception, or a broken engagement caused by one party or the other. But in this case, there is mention of nothing but a broken vow.

Here is a reason for reflection: to promise, to stake your name and reputation on that promise, and then fail to keep it—this was once something for which one could be held accountable. When did the breaking of a promise cease to be an offense?

It is the year 1796. Ioniță swore he would marry the Nameless Girl. A beautiful autumn in Bucharest, perfect for weddings. But Ioniță changed his mind. Humble, ashamed that he had stained his own character, he goes to Calița and tells her he no longer feels like getting married—it is far too serious a step. That’s life: people change their minds.

Calița is furious. Her daughter’s name will be sullied; she will remain forever the rejected one in the eyes of the neighborhood. Things cannot remain this way; the insult demands redress.

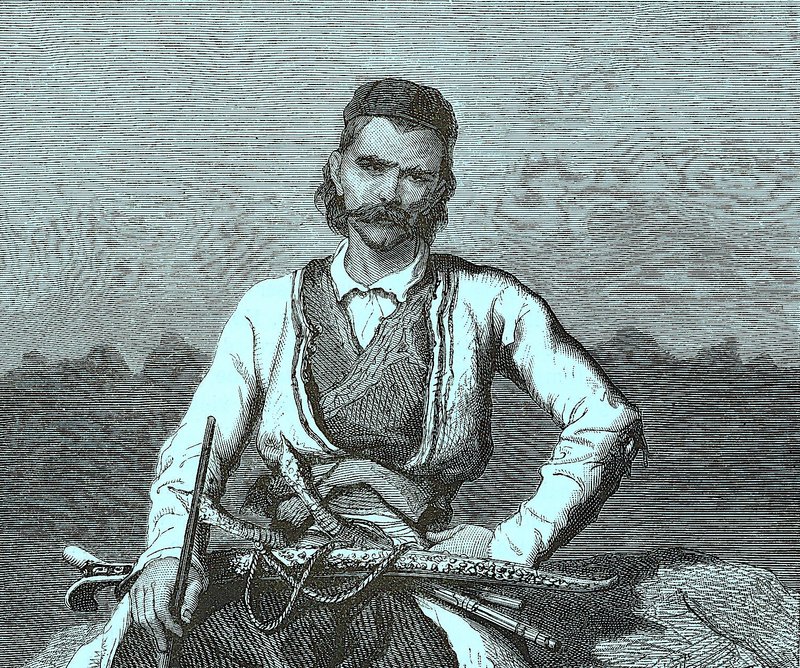

The Metropolitan takes the matter seriously and summons Ioniță for a discussion. We can picture him, can’t we? Metropolitan Dositei—whom I’ve mentioned before, an important character in The Phanariot Manuscript—a learned man, but rather brusque, a man of action. By contrast, Ioniță is a man who feels guilty. Naturally, he is young, overwhelmed by emotion. He probably looked like the Montenegrin drawn by Théodore Valerio that I showed above. In any case, he was nothing special. He wore a long, striped shirt, cinched with a shawl, and over it a short jacket. A fez or a carelessly wrapped scarf around his head. Shalwars tight around the calves. Solid boots made of oxhide. It was the cold season. Over everything, he wore something like a raglan or a sheepskin coat, covered in patterned cloth. That is what Ioniță looked like when he entered the Metropolitan’s presence.

From the outset he confesses that he has nothing against the girl—he is simply very poor. What is he to do, he asks, when even now, alone, he barely has enough to eat? Dositei first insists on the value of the sacred oath, twisting the knife in the wound. And so Ioniță offers to give the girl 500 talers so she may forget the promise, which he now considers rash. Poor as he is, he still has 500 talers. What did that mean? Five months’ salary for a Divan official. Or twenty-five salaries of Dragnea, the worst-paid schoolteacher in Bucharest.

The Metropolitan is not satisfied. He senses Ioniță’s weakness, sees that he is lost. And so he begins the work of persuasion: he promises to put in a good word for him with the Prince, to secure him a respectable position and a role in society. Naturally—only if he marries the girl.

At first, Ioniță agrees. Călineasca throws herself into wedding preparations and spends money. But autumn passes in discussions and negotiations, in audiences at the Metropolitanate. Advent arrives, so everything is postponed until the beginning of the following year. But that, too, seems acceptable.

Only the year 1797 begins badly for the girl. Ioniță changes his mind again. Despite the wedding expenses already incurred, he is ready to assume the consequences of breaking his promise. He does not want to marry, full stop.

But the expenses for the marriage have been considerable. No matter how poor she was, the girl needed things. From dowry lists belonging to other neighborhood families, we know that a girl of modest condition had to bring at least two sets of clothes for herself and two for the groom, accessories, jewelry—at the very least some glass beads, silver earrings—then pots, sheets, and everything else needed for a household. Calița had therefore purchased these items, along with part of the food for the wedding feast, and so on.

And despite all this, Ioniță has the nerve to change his mind!

The Metropolitan is indignant. He understands that marriage is a life decision, but Ioniță’s indecision now seems to him an insult—also to himself, as a man of the Church. And so he delivers his verdict without remorse: Ioniță must pay the girl 1,300 talers. Of course, he knew perfectly well that the capricious young man did not have such a sum.

Meanwhile, Ioniță himself has become more assertive, has gained courage. Perhaps he already had advisers, or had simply grown accustomed to the idea that he had broken his promise—and that was that. In any case, he no longer feels like negotiating with the Metropolitan. Instead, he goes straight to the Palace and files what we would today call an appeal against Dositei’s verdict. He feels wronged; he feels coerced.

Ipsilanti, who was then on the throne of Wallachia, reads the complaint and puts an end to this long process of hesitation: Ioniță must pay the girl 1,300 talers within at most one week, or present himself before the Metropolitan so that he may be married to the girl on the spot.

It was February 7. The fate of the Nameless Girl was finally decided. In any case, she has no say in the entire story. She is left with only a few ways to adjust her life: flight into the world—or debauchery.