During the long Hellenistic period (3rd century BC – 3rd century AD), unleashed by the passions of the Macedonian, the world kept moving—from Mesopotamia toward Egypt, with a stopover in Crete. Each traveler carried what was most precious: foods and garments, but also beliefs, rituals, and, above all, superstitions.

Cults of Eastern gods became fashionable in Rome, while Greek philosophy made its way toward Alexandria.

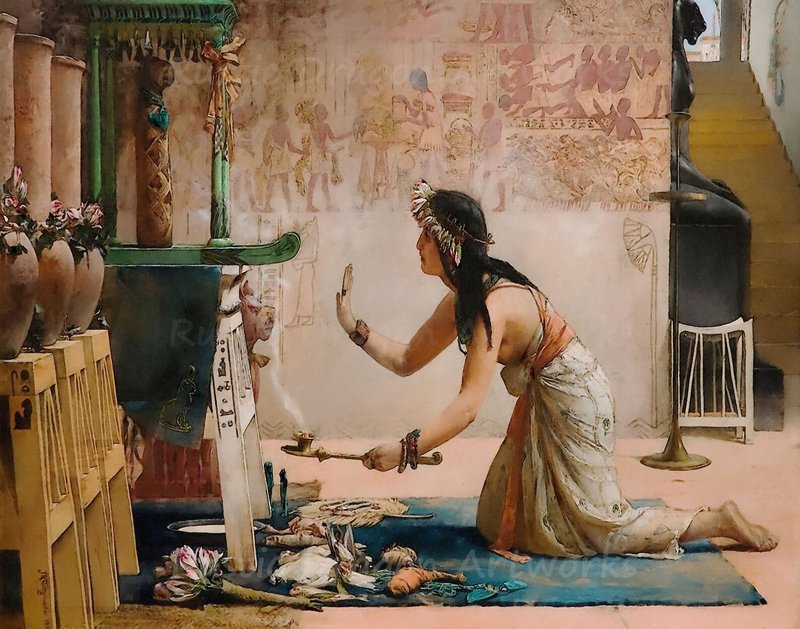

By the end of Antiquity, the Egyptian goddess Isis was paraded through the streets of Rome, and many had become her followers—an expensive devotion, as Apuleius tells us. Depicted with a child in her arms and symbolized by the rose, she was among the most popular divine figures. Even after the rise of Christianity, her memory endured, dissolved into another Madonna.

Among the lesser deities was Bastet, also imported from Egypt, worshipped especially by women and represented as a black cat. Her followers honored her with numerous statues—small ones for the hearth, larger ones placed before houses like guardians. There were amulets, vessels containing elixirs, ornaments, and many other objects. The cult spread from Athens to Rome, without ever becoming dominant.

By the 4th century AD, temples and small communities devoted to this cult still existed. On the margins of the Eastern Empire, somewhere along the shores of the Bosphorus, lived Myrrhina, a priestess of the goddess Bastet, known locally as Aliuros. Her story is the one we tell today.

Her life was exactly as she had wished it to be. Her freedoms were tied to a neighborhood temple and to a small group of believers—mostly women—who would have followed her anywhere. Their rituals were discreet, always involving potions that filled the Greek quarters, by then Romanized, with long-desired offspring. Myrrhina wore fine garments and, above all, a black velvet mask—a cat’s head so expressive that one could swear it was alive.

In the evenings, they gathered to sing hymns dedicated to the cat goddess. They tasted perfumed drinks and danced together until dawn, when each returned home.

In daily life, Myrrhina was a quiet, withdrawn woman. She lived in a modest but elegant house with two white columns, and on the steps stood, tail curled neatly, a dark cat adorned with earrings and beads—a statuette she had commissioned in Rome.

Her life might have continued peacefully had Christian terror not begun. Once established as the dominant religion, Christianity worked to ban the old cults—now labeled pagan—and, more generally, any small group that did not bow to the main body, exactly as happens even now, in all domains. Considered heretics and witches, non-Christians were killed, expelled, forbidden. A cross was placed upon their temples.

Understanding the situation, Myrrhina hired a ship, intending to reach Colchis. She gathered her faithful followers, took what she could—including the statue—and set out on what she imagined would be a long journey, though it ended quickly. The sailors extorted her and abandoned her in Dionysopolis, a miserable port that centuries later would become Balchik.

Settled on the outskirts of the small harbor, Myrrhina lived among other outcasts: rejected Christians of the time, followers of even more fragile gods than Aliuros, or simply people expelled from Rome—thieves, killers, and other wretches.

Yet her deeds endured. The nocturnal gatherings gained fame, and women wearing cat masks began to be invited to secular festivities. Myrrhina found her place. She acquired admirers, suitors, lovers. The people adored her, calling her the patroness of mysteries. Christians named her Domna, while some Goths—great lovers of poetry and dance—attributed magical powers to her, especially since her gatherings always featured a drink made of wine and rose petals.

In this mixed and exiled world, the divine cat and her pleasure-laden rituals took root.

And pleasures, as you know, spread at the speed of light. Few remembered the cat goddess herself, but the cat dance spread rapidly through many Balkan communities. Women and men fashioned cat masks and indulged wildly, each adding something to the growing spectacle, which over the years became orgiastic. It persisted long after Myrrhina’s death, until lawmakers finally put an end to it, banning it entirely.

The memory of pleasure fused with the memory of the cat, and at some point the prohibition turned against all black cats. The superstition spread that if a black cat crossed your path, your entire day would go badly. People focused on color, forgetting the origin. Especially since black animals had long been used in religious sacrifices, the dancing cats and the goddess were erased from memory.

Despite the superstition, cats continued to be raised as companions, even as members of the family, regardless of color.

As for Myrrhina, when she died, someone carved the word Domna on a stone and drew a cat’s head. Later, in a deeply and categorically Christian world, a careful hand added a cross. Thus, centuries later, when archaeologists uncovered Myrrhina’s grave, everyone agreed it must have belonged to an early Christian goddess—proof, they said, of an ancient and liberal Christianity in those lands.

For the Romanians, neither Myrrhina’s story nor the cat cult truly mattered. The antiquity of cats in Romanian domestic life vanishes into the mists of time, hundreds of years before Myrrhina’s arrival. On Cucuteni pottery, cats appear in dancing chains. Even the word pisică (“cat”) attests to their deep roots, being thoroughly indigenous. While many animals arrived together with their names, cats were domesticated much earlier, when forests were full of wild cats. According to another ancient superstition, any wild cat could be tamed through a magical formula—pis-pis. Any wild cat would leave the forest and follow the person who knew how to whisper pis-pis. The history of this invocation has been lost, but from it the Romanian word pisică was formed (apud Șăineanu).

Cucuteni