I never liked writing letters. How can you bear the thought that what you write now will reach the recipient in a future that no longer has anything to do with you? Besides, I am a hurried person. Why should I wait for an uncertain reply, not knowing if or when it will arrive?

Once upon a time, I loved writing notes at school, during class. The true and living correspondence took place in middle school, when I would wait for the reply like Genji or the Princess of Clèves, my eyes fixed on the sender. I could see the back of his neck and feel his effort, watching the shoulder moving to the rhythm of emotion fallen into otherwise banal words, like the math teacher is a sinister idiot.

Long letters written in the shade of August afternoons seem to me as dull as syrup cakes in a shop window. To write with the awareness that an unknown eye will read you in a thousand years! What a ridiculous ideal. Van Gogh’s correspondence. Cioran’s letters. Poor Fănică’s little note. Texts for voyeurs who imagine that another person’s intimacy is better than their own.

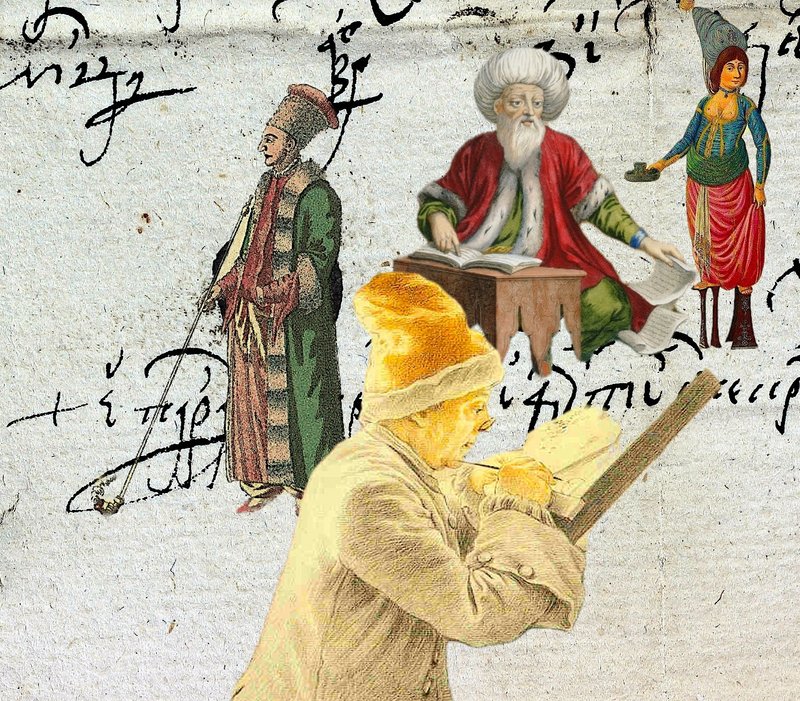

In summer, people write short letters, without unnecessary details. A nobleman from the Brăiloiu family has such a letter written in May. The world was waking up, the grass was burning, and the nobleman wrote in watery green ink: May 16, 1806. “Please buy me some leather shoes, without heels, but green — one pair; and two black pairs.”

Then he remembers he needs other things as well and lists them without further explanation: “celery or celeriac, kohlrabi, biscuits, rusks, mineral water.”

Letters from May are sometimes about cherries or meetings. We like to imagine they are love letters. Letters placed in yellow envelopes, like in the old days, and then kept in chests and drawers. When I think of May letters, I see them only sleeping, often unsent or unopened.

One velvet autumn, I found a book about the Foreign Legion in whose margins a man had written a letter to his beloved. He had been sentenced to death for stealing the regiment’s money and had written his misfortunes in greenish ink on the margins of a book he had never even read. The lines were tiny, almost erased, and I struggled hard to decipher them. Then, with time, the former ink melted away completely, and with it the dying man’s story.

Perhaps since then I have been left with the impression that true letters are written in autumn. Though I admit that during Lent many desires and cravings are put on paper. In a foggy February of 1803, a nobleman from Craiova writes to his supplier in Sibiu: “Since a very heavy snow has fallen here, so that there is no means of finding snails for food, and since we have entered the holy fast, I ask you kindly to order that for these ten zloți as many snails as can be bought should be purchased.”

Soon the reply arrives, brought by the caravan transporting orders into the city. The merchant writes briefly: “2,000 snails — 10 zloți; 2 cups — one leu; 2 jugs — 18 zloți. A sack of snails — 30 zloți.”

The nobleman read it, decided quickly, and sent his letter the very same day, while in the Sibiu marketplace thousands of snails were agonizing.

But there are also letters without season, dealing with serious matters, stories and indirect requests, like an epistle from Barbu Știrbei, from 1808: “Here there is an evghenis, a man of His Highness Prince Ipsilanti: he has a child whom he wishes to make a doctor, and since he is a very good friend of mine, he asked me to write to you, so that he might send him to Beci (Vienna) to spudacsească (study) there and learn…”

Of course, Știrbei needs information; therefore it is a long letter. It took the recipient a day just to read it. Then he set out to inquire about the matter, lost another day writing a proper letter for princely eyes. After about a week the main facts were known, but there were still questions, so this correspondence lasted an entire season.

I confess I adore email — fast, quasi-anonymous, comfortable.

Only sometimes, like now, for instance, do I still write on glossy paper, arranging the lines like violet alleys in a Voltairean garden, doggedly hoping that someone will think of the hand that is writing now.