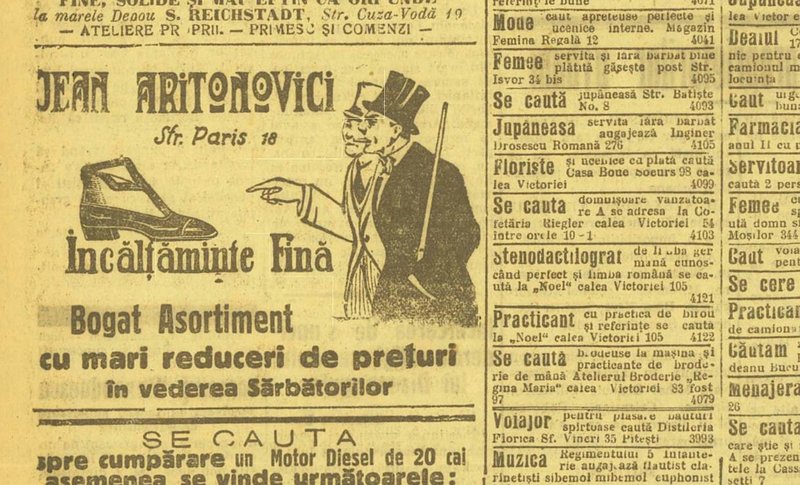

On Paris Street, at number 18, there was a shoe shop around the year 1924. You could learn about it from the newspapers of the time, where advertisements appeared quite often. The owner was Jean, a fairly young man then, the son of a merchant who owned an agricultural tools shop on Colțea Street.

The old man’s shop was called La Soare (At the Sun) and had reached its peak before the war. After 1915, it is unclear whether it still existed at all; in any case, the Aritonovici family had placed its hopes in the son, Jean.

Jean began his ascent with a shoe business, sourcing his goods from Armenian workshops in Bucharest and soon completing his stock with German-made pieces brought in from the newly acquired territories of Transylvania. Since he was not particularly wealthy, he transported the merchandise himself, using a second-hand truck—especially as he enjoyed driving.

Even so, the shop ran at a loss. It had no foot traffic, and the newspaper advertisements announcing promotions failed to bring him the financial success he had imagined.

Thus, from a notice published in the Official Gazette, we learn that by around 1933 he had failed spectacularly, struck down by the economic crisis and other misfortunes.

We discover that he was summoned to court, charged with fraud. Nothing remained of the shop owner who paid for advertisements and offered holiday discounts. The document also states that he was a driver and a swindler. He had no registered address; his residence was unknown. From this, we understand that the shop on Paris Street had existed in rented premises and had already become history.

One cannot help but wonder what had happened to him.

Jean was a capable man with grand dreams, but the times—like all times—were not kind to such dreams. Beyond this, Jean had an almost harmful passion for shoes. Perhaps it would not have mattered, had there not also been a philosophy behind it. He had always believed that a man’s feet reveal who he truly is.

Even in school, he enjoyed studying shoes—first those of his teachers, pacing back and forth in front of the blackboard, most often wearing sturdy shoes with thick soles, sometimes bought for life. Yet even so, he could see clearly how some shoes bulged at the edges, while others revealed a pitiful, persistently battered toe. There were cracked shoes, soft shoes soaked in polish, or clogged with crude tar. He saw shoes polished so well you could fix your hair in them, with laces that looked untouched, yet which revealed—through the tongue folded over the shoe—the cautious and miserly souls who wore them.

Jean lingered in the streets, staring at shoes. Sometimes he leaned against a wall, hands in his pockets, chewing over the information that assaulted him.

Women’s shoes did not interest him. Only men’s footwear was worth observing. Women, to him, were not viable characters. They had no place in his story. Only men deserved to play a role.

He was especially fond of shoes covered with gaiters made of Morocco leather—or better yet, velvet. Above all, he loved patent leather shoes, a black so deep it reminded him of wartime windows, lined with camouflage paper. Among them were shoes cut low at the heel, finely edged or stamped, which made him dream.

He despised shoes with wrinkles, shoes worn by men who walked on their toes. His philosophy had proven accurate: whenever he dealt with shoes split by a wide crease, he knew their wearers were indecisive men, who led you on and with whom no business ever came to fruition.

There were also misshapen shoes, which often belonged to trustworthy men, yet Jean knew they would compromise you and were not worth the risk. Solid shoes—boots with rounded toes—brought inflexible men down on your head.

He also had a weakness for light-colored shoes, made for adventurers and generous men—men who cared less about how long a shoe lasted than about the happiness a beautiful thing could bring.

He had many such ideas, all of which justified his choice of becoming a shoe merchant. But he went bankrupt. The Great Depression began, and all he had left was his truck, which he used to make a living by transporting goods for others.

Everything collapsed one November day, when the cold froze your nose—an unusually harsh winter that year. Jean dealt in second-hand goods: poultry, sacks of feathers, diesel in metal canisters, and many other items no longer found at the Obor market, which he brought in from villages farther away.

That autumn day, he entered someone’s home carrying a sack of cornmeal. The man paid part of the money, but the goods cost more. Jean waited in the entryway for the rest. Near the coat rack stood a pair of shoes that looked new. They were beige, perforated with holes of varying sizes, and the laces had a special charm—white, slightly wider, and silky.

At a glance, he knew the shoes were exactly his size, and he could not resist. He grabbed them. Since he had not received the full payment for the cornmeal, he took the sack as well, and within a minute he was racing down Moșilor Avenue, without a plan.

The owner of the shoes did not consider him a thief. We do not even know whether he made the connection between Jean and the shoes. He reported him instead as a swindler, which led to Jean being summoned to court.

But Jean had no address. He could not be found. For months, he was sought.

Jean traveled extensively that winter, and by summer he was walking his shoes through the streets of Odessa, where he took a photograph—preserved to this day.