One of the books that circulated in the Romanian Principalities was The War of Troy. It originated with Homer, without being a translation, reconstructing the story of Helen of Troy while naturally adding other deeds, commentaries, and characters—especially Christian ones.

Tudorachi sold a few turkeys and bought himself such a book: a handwritten copy, ornamented with drawings. The reading unsettled him completely, so much so that, by the end, he felt compelled to write a few lines on the title page. He was not interested in Achilles’ bravery, but in a woman’s infidelity. Tudorachi confessed that he too had “hit his head against a bridge,” and therefore wished to warn future readers about the subject, for in this book they would find a small consolation, discovering that others had suffered as well because of a woman’s unfaithfulness.

What had happened to Tudorachi? He was a man of some means—he owned a turkey farm somewhere above Pitar Moș, as well as a small shop selling sundries. He therefore considered himself marriage material. He believed himself hardworking and took care to display his diligence on all occasions, expecting applause in return.

Of all the women in Bucharest, he had set his sights on Polixenia, the daughter of a Greek man involved in rather unclear business ventures. This woman had bewitched him in a diabolical way: whenever she passed by his gate, she would extend her hand from the carriage window and wave her glove.

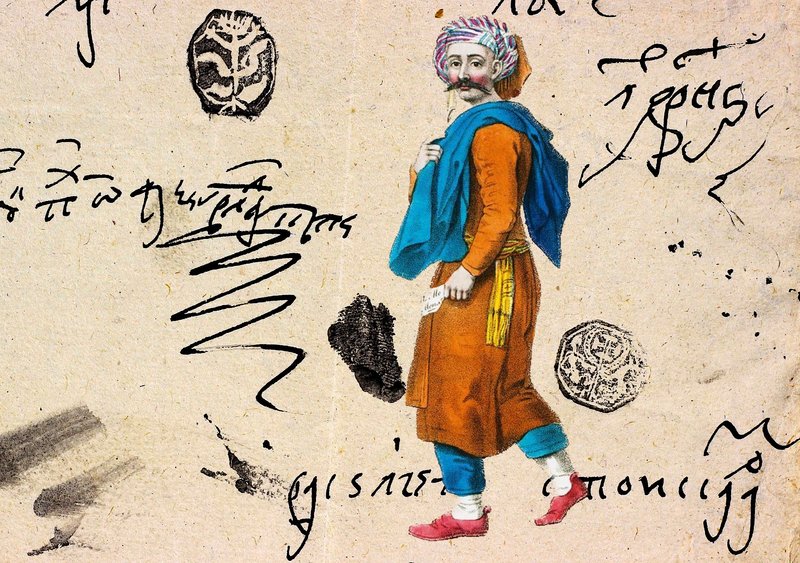

Tudorachi made sure to be at his gate precisely when she passed, having carefully learned her schedule. For this, he prepared himself in advance, adorning himself as best he could. First, he bought a brown fez, over which he wore a frothy white scarf patterned with copper-colored flowers. Then he took care to shave, leaving only a thin line of mustache, meticulously groomed. He owned special “gate shoes,” purchased from Lipscani merchants who accepted neither bargaining nor discounts. Finally, he even bought gloves, which he did not wear, but kept in a metal box, for the day when an occasion might arise.

He already imagined himself married to the Greek woman, whom he had never seen up close, but whom he could describe in detail thanks to an imagination that had not been idle, working tirelessly on a portrait molded from desire. He spoke of Polixenia with such fervor that his friends regularly encouraged him to marry her.

Among them was a drunken schoolmaster who doubted that Tudorachi would ever marry. And what kind of friend was that, to scoff at lofty ideals?

Annoyed and convinced that the schoolmaster deserved a lesson, Tudorachi adorned himself with a tall hat—a tubular ișlic made of broadcloth with a silk top—something not seen at every corner, as it had been made to order, specifically for such an occasion.

He bought a small basket of almonds and grapes and knocked at the Greek’s gate.

Naturally, Polixenia herself was not needed at first. He would speak with her later, after hearing her father’s opinion. The Greek raised an eyebrow and asked whether he had spoken with the girl. “Why should I?” Tudorachi replied. “Every time she passes by me, she signals with her glove.” And he launched into a story about the months he had spent waiting for the exact day and hour, standing stiffly at his gate.

The Greek made no comment, but went to ask Polixenia.

I could never describe Tudorachi’s waiting: left alone in the salon, near the door, with a monumental hat on his head and a basket of grapes in his arms. All his tension melted, however, when he heard laughter somewhere in the shadows of the house.

Then the Greek returned, relaxed, and explained that it was all a misunderstanding. Polixenia waved her glove for the coachman, to indicate which direction to take. Wasn’t there an intersection there? That was it. He had not been attentive. Not all waving gloves are signs of love. He should calm down and go home.

Tudorachi bore the incident badly, holding Polixenia responsible—a dubious and perfidious creature who had maliciously misled him. His suffering grew all the more when, shortly thereafter, Polixenia married a young Greek, much like herself.

His only consolation came from his friend, the drunken schoolmaster, who placed a book in his arms. “Read, Tudorachi,” he urged him, “and you’ll see what these Greek women are capable of!”

Thus The War of Troy entered Tudorachi’s house. He was so deeply impressed by the Homeric story—even in its distorted form—that he left a note which can still be read today, on the carefully copied manuscript made by a schoolmaster, where a deeply disappointed man recorded his thoughts:

“Be careful,” he writes, “if you read this book, not to trust a woman’s vows, and guard yourself well lest you hit your head against a bridge, as I did!”

It is a fine review to sell a love story—especially in spring, when cats get married and women put on their shoes and leave their houses.