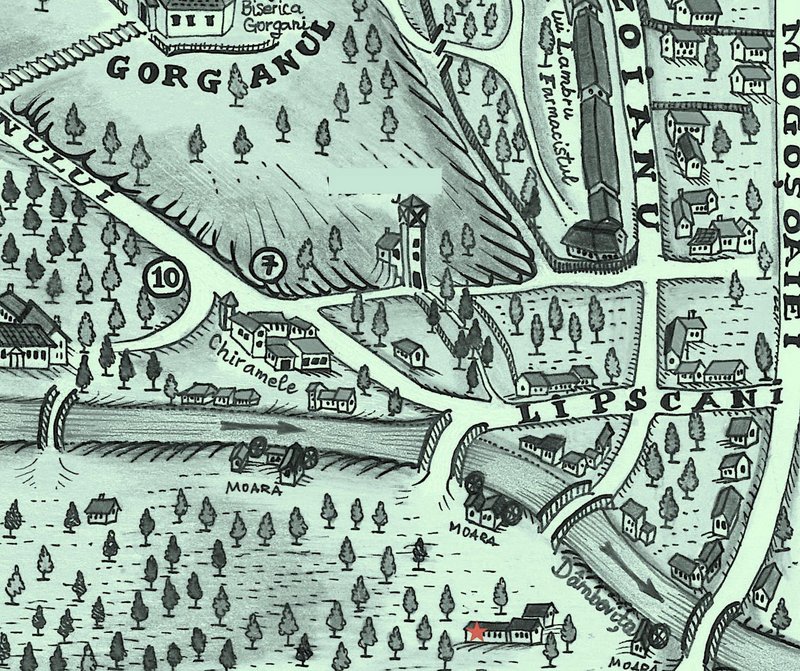

Among the many papers of the Phanariot age, a map has survived—not something elaborate or precisely executed, but rather a drawing, a sketch of a Bucharest neighborhood, with streets and various houses, some bearing the names of their owners, here and there even silhouettes of people. And among all these, one detail caught my eye: a stain. It looked like a violently beating heart or a burst balloon. A red mark, on the edge of the map. In any case, it was clear that someone had placed a sign there.

Since the area was familiar to me—somewhere beyond the Dâmbovița River, not far from Gorgan and the famous house of the chiramele—I began to dig. Beneath the dust accumulated over history, beneath layers of perverse words that alter the meaning and destination of facts, beneath the mold carefully arranged there by obtuse exegetes, I found the neighborhood intact, and Morarilor Street, which began beyond the Dâmbovița, at the bridge, winding serpent-like past the mills, through a wasteland with bitter plum trees and vines, past a mysterious house, on whose rooftop a gentle blinking eye shimmered.

Along this street, day after day, had passed Panaitache, an illustrious writer who, around 1760, had distinguished himself by composing letters capable of moving mountains. And what letters he wrote! From letters of gratitude to those that could ruin you so thoroughly you would not recover for years; from confessions and narratives of hidden sins to the most inconsequential love letters—those being, for him, the easiest of all. For a true love letter, we might say today, is composed by someone who has never loved—by an uninvolved person. And Panaitache had never known love; he kept it at a certain distance. His only pleasures were writing, the midday nap, and solitary dinners—more precisely, dinners in an iron silence.

This deacon, overflowing with words and talent, came upon the house I mentioned.

It was not the area that drew him, nor did he question the eye on the roof, the palpitations of its divine eyelid. Something else enchanted him. From the chimney, from the cracked doors, the windows, and the unseen fissures of the masonry emerged an aroma that drove him mad. It was the smell of pastry, of meat into which entire packs of garlic had given up their souls; but also the smell of grilling, of aromatic fats, of herb-laced meatballs, of fresh crusts sprinkled with a drop of vinegar and a dusting of pepper. And when I say pepper, I mean those with fleshy bodies and the breath of passionate people.

There was, in that food, a chickpea that someone had forcibly soaked in plum brandy and left to steep in sauce. And as if that were not enough! Rising above all was cinnamon from honey artfully spread over oven-roasted ribs, over mushrooms tormented in oils, over plums stuffed with pistachio kernels and tiny pieces of meat, perfumed with mint and threatened by a fragile basil leaf. And finally came the scent of dill, compelled to blister within minced meat, and of vanilla, which treacherous sour cream had diminished, forcing it to renounce the selfishness that had made it famous.

In short, from the house on Morarilor Street emanated the smell of the life everyone dreams of—plus the refinement of an elite cuisine.

Panaitache remained at a distance, inhaling the house’s delights. The next day, on his way to meet a client who wanted a letter with Biblical quotations, he decided at the last moment to detour once again toward the house of culinary aromas.

This time he lingered for nearly an hour, imagining what was being cooked. And what did not escape through the window! Cheeses blended with butter, refined pâtés with onion, pepper pastes, turkey neck stuffed with pears, assorted sausages, cured meats lamenting under presses or in smoky mists—in short, there was an overwhelming mélange of scents, a cry for help.

Panaitache continued to come in the days that followed, as questions multiplied: for whom was so much food being prepared? What happened daily in a house that now seemed hardly a human dwelling at all? No movement came from inside, apart from these olfactory summons.

And finally, on the fifth day, Panaitache asked himself who the person cooking might be.

At the end of a week in which he had written nothing, he gathered his courage, adjusted his turban, checked the small clasp, fingered his beads, kept one hand in his pocket, knocked on the front door—and waited.

A shadow fell over Morarilor Street, as often happens in Bucharest, and the eyelid on the roof trembled. Then the door opened. On the threshold appeared a figure of ice, who gestured that he might enter, and Panaitache understood that a miraculous encounter awaited him.

Everything in that house was unusual. Among pedestals and garlands of flowers, one glimpsed now and then a skirt, fluttering silk, a curtain ready to fly.

In the center of a room lit like daylight, a woman who seemed familiar sat on a divan, waiting for him.

He had come to learn who cooked there and assumed the woman was the author of those aromas. But which aromas? Nothing of what he had smelled for an entire week remained. The strange house smelled only of acacia blossoms.

The woman smiled indulgently, as goddesses do, and did not even need to ask. The answer was already prepared: If you came here for food, know that no cooking takes place in this house. I know—you sensed meat, but those were merely the calls of your belly, your own joys. In truth, I wanted to commission a letter.

The deacon instantly became a writer with a client before him, pulled the quill from behind his ear, ready to write. The distinguished woman, dressed in Maltese silk, asked for a love letter, offering a few details about the recipient. They agreed on a price—far from negligible—to be paid upon completion.

All night he wrote, imagining whom the mysterious woman loved. As the letters formed, the aromas that had drawn him to Morarilor Street returned to his mind. There was a fascination in the whole affair that made him pour more enthusiasm into this letter than into others.

Yet the further he progressed, the greater his dissatisfaction grew. He, who had written for princes and princesses, found himself faltering, searching for words. Instead of passionate kisses, roast pork came to mind; he remembered stews, cinnamon scattered through streets. Perhaps he had lost his talent. Perhaps he was blocked.

When at last he finished something—a first draft, we might say—he rushed out, ostensibly for an opinion, but truly to see the mysterious woman again. But the house, with its sleeping eye, had vanished entirely. On Morarilor Street, among mills and gardens, three houses now stood where the aromatic house had been—a potter’s, another potter’s, and a slipper seller’s. He tore up the letter, which was beneath his talent anyway, and, transformed into lily petals, threw it into the Dâmbovița, watching it drift away.

Panaitache wandered the area, reconstructing events. He drew a map—which I include here—marking the spot where the house with the eye had stood. Then came the holidays, life moved on, and the deacon returned to his commissions.

One day, a courier knocked at his gate with a letter. Panaitache opened it without expectation, and from the first words his eyes widened: it was a love letter—the worst one he had ever written—for the mysterious woman. As he read, the sentences turned to mist, a haze in which gathered the foods he had never seen. At the end, when even the final line became vapor infused with roasted almonds, he realized he was holding a sheet of vellum that, a moment later, turned into fly wings.

Thinking of the bridge over the river, the mills, the plum trees on the riverbank, the house with the eye and the woman on the divan, he finally reached the understanding he had hoped for.

First he prepared a bowl of meatballs laid on a bed of dill. Holding it in his arms, he ran across the bridge, past the mills, to the place where the house with the eye had once stood. He placed the meatballs as an offering and waited, as he had once waited for the door to open. It did not take long.

Inside, everything was unchanged. Among veils and flower garlands, the unknown woman smiled—or rather, a version of her. For looking more closely, he realized she was even more familiar than before.

He approached the divan, questions crowding his mind, but upon reaching her he froze as before a mirror. The woman in Maltese silks, her hair fastened with rubies, smiled at him with a familiar irony. She toyed with her beads, searched the pocket of her trousers with the other hand. From her curls dripped little stars of ice, and behind her ear she held a quill—exactly like his.

The mysterious woman who had summoned him through food, the queen of vanilla and fragrant pastries, was himself. Or rather, a copy of him. He had kept his distance from love without realizing that the farther he moved from others, the closer he came to Narcissus’ gate.