Sometime during the Phanariot century, among many other curiosities, there existed a botanical garden—an educational experiment run by the teachers of Saint Sava, which in time came under the care of the monk Onisim the Blond. Roughly where the statues now stand, near today’s University Square, there was a greenhouse filled with exotic plants and botanical trials, foremost among them the grafting of roses. Onisim, in particular, had a gift for making a clean, artistic cut, attaching one branch to another of a superior strain, dressing the wound with manure and strips of cloth soaked in honey. At other times he ran after seedlings or received seeds from Greek monks. But by far the most spectacular botanical conquest was a flower destined to bloom on Christmas Day.

The people of Bucharest were astonished by the precision of this promise, and although many doubted it, there was no one who did not hope it might be true. Never before had anyone heard of a plant blooming in the dead of winter—and precisely on such a holy day, filled with both sanctity and indulgence.

Although Onisim was not talkative, his prediction grew legs and ran through the entire city, becoming more seductive and eagerly awaited with each passing day. And as the story passed from mouth to mouth, new details emerged. It was said to resemble a water lily growing from the back of a hedgehog. Its size, according to the market folk’s imagination, reached fabulous proportions, comparable to the ișlic hat of Ban Filipescu.

As for its scent—what can I say? It was impossible to describe.

The flower was kept in a greenhouse heated with great effort, and Onisim liked to spend his evenings there, staying late into the night.

The students of Saint Sava held their botany lessons in the greenhouse and had, of course, seen the plant. Yet they played the mysterious ones, offering little information, except for the promise that on Christmas Day anyone would be allowed to see the miraculous flower, even to make a wish or pray before it. Onisim was willing to let anyone enter the greenhouse. Naturally, at the entrance there would be an alms box, and for those interested, small blessed crosses and other trinkets, at modest prices.

The merchants of Lipscani smiled ironically, but behind their smiles lay a desire they were willing to pay for. Money, rank, and above all love—these were the things on the minds of Bucharest’s inhabitants then. As now.

For about two weeks, Onisim’s flower was the city’s number one topic, and the color of his eyes—blond shading toward chestnut—changed repeatedly, depending on the storyteller’s fancy.

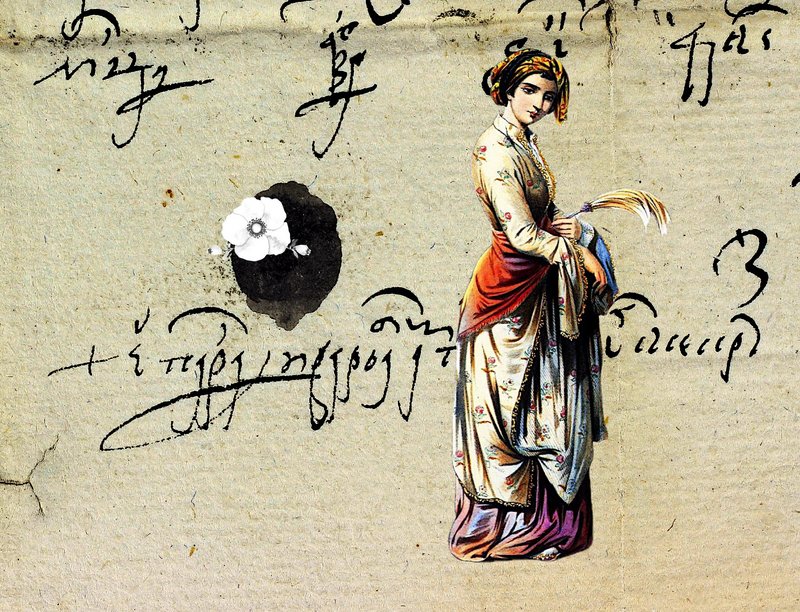

Among those determined to reach the garden at all costs was Minda, the fritter seller, who roamed the streets with a tray, selling everything her sisters fried: cheese fritters, fruit-filled balls, flatbreads as large as skillets, sweet rolls, and especially walnut-sized doughnuts, artfully arranged in a wicker basket to leave room for a small cup of yogurt.

She had only one dissatisfaction—her nose: a bit too large, a bit too bulbous. If that flower truly was holy, perhaps it could make her nose smaller. And how could it be an ordinary flower, grown by honest monks full of grace? Someone had even mentioned its perfume, claiming that once you inhaled it, you were utterly transformed.

On Christmas Day, the doughnuts were gone. Minda stood at the door of the Caimata Church, selling sugiuc all day, then spent the evening visiting neighbors, dreaming in the steam of mulled brandy, delighting in the little angels of wine.

Only when she was about to go to bed did she remember that she had missed the miracle. Sleep would not come, and she felt as though the Christmas flower was calling her, summoning her to the courtyard of Saint Sava.

She put on her cloak, pulled on her boots, and ran.

From the Colțea Tower, the watchman announced midnight, while fine snow dust fell from the crowns of trees.

The monastery gate was closed, and the street lay deserted all the way to the Dâmbovița River. She could not turn back, especially since the hem of her coat was already soaked. She climbed a wild cherry tree, jumped onto the wall, and looked cautiously. The courtyard slept. The cells lay in darkness. A lantern burned near the cellar, and at some distance the path toward the greenhouses was visible.

Minda jumped down into the courtyard and approached in small steps. The central greenhouse, with its many windows, looked like a mound of doughnuts generously dusted with sugar. She wiped the glass. Near the door stood the alms box, and not far from it a candle. The door was open.

She entered with a shiver that would stay in her blood until death.

In a tall pot stood the flower: truly a hedgehog from which countless petals had somehow grown. In the dim light of the greenhouse, it looked like a cabbage made of ice. Perhaps it was not a real flower at all, but a ball of silk, a festive ornament. She had to come closer, touch it, and above all smell it. Only then would she truly know.

As she touched the flower, she realized she was not alone. A damp log hissed in the stove, and behind the flower she discerned a silhouette of flesh and bone, a specter that froze the blood. A perfume spread everywhere, carrying the strength of ripe fruit and a faint trace of lemon.

Minda inhaled deeply and looked again at the silhouette, focusing on the details. It was a naked man, a figure of snow. In one hand he held a small heap—a part of himself, precisely the part he was dissatisfied with. Clearly, he had placed all his hopes in the powers of the plant and awaited the fulfillment of his wish. The man, as far as could be seen in the winter’s glimmer, was Onisim.

So the flower truly had grace.

Minda touched her nose. The monk sighed. And the night was long as a story, precious as a parable—worthy of being placed in a book.

In the days that followed, Minda’s nose grew slender, acquiring elegance. As for the monk Onisim, I must tell you that he renounced monastic life and lent his strength to the development of the doughnut trade.

The greenhouse fell into ruin. In its place stretched the shadows of the Ghica cemetery, which themselves vanished in time, until decades later the statues appeared there—standing firm to this day. Mysteriously, in winter, around this time of year, an ancient vapor rises there, a perfume of honeysuckle and crushed unripe grapes. Within its essence linger the loneliness of a monk and the surviving hopes of a woman.