(translation)

On a winter night in the year 1702, a sleepless woman from Bucharest began making pies. Among them all, the pumpkin pie twisted the mind most powerfully, spreading an aroma of vanilla, a faint breath of basil, and the scent of thick rind, scorched by fire on both sides.

Naturally, the rest of the world was asleep, even though the sweetness of the oven drifted from Colțea all the way down to the waters of the Dâmbovița, where, at that hour, catfish dreamed wrapped in mud, and tadpoles lay beneath the breath of great Murta, lord of dreams and waters.

Pleased with his powers and with the stillness of the night, Murta floated beneath a bridge, inhaling effluvia of silt and willow. But into his reveries crept the aromas of the kitchen in Colțea. Pumpkin! Exactly what he loved, especially at the beginning of December.

He slipped through the streets and reached the sleepless woman’s house.

At her window, Murta looked like mist, and the woman thought the glass had fogged. The table was laden with pies, arranged on a tray with silver handles.

Murta delighted in the scent, advancing slowly through tiny cracks in the window frame, through minute slits in the glass.

The woman—perhaps I should mention—could not sleep because she had slept too much in her life. As a girl she slept so deeply that her worried parents sent her to Târgoviște to learn the art of weaving kilims. She would have stayed there much longer had her parents not died suddenly of plague.

Returning to the family house, she discovered the pleasures of cooking. And when you lack nothing, when you have no fear for tomorrow, when no one stands over you ordering your life or sending you to workshops, dreams abandon you.

Often, in the monotony of steam and frying smoke, a boundless sourness rises. The pie-maker resembled an embittered old man, a flower withered by drought.

To Murta, she was merely a stale breath, one he felt compelled to repopulate with dreams. In his art as master of fabrication, there was a theme he loved most: perfumes. Any breath of life led him toward elaborate actions, until sometimes the faint scent of roasted almond turned into a poem, or even an epic with hundreds of characters. The insomniac inspired him to summon gardeners with sapphire eyes, women devoted to nocturnal games, winged horses and festival singers, book-reading flies and goblins weary of all the harm they had done.

The night was long. By morning, the pies had cooled, and their fragrance had been drained by the insatiable Murta of dreams.

That morning it snowed lightly, with large flakes.

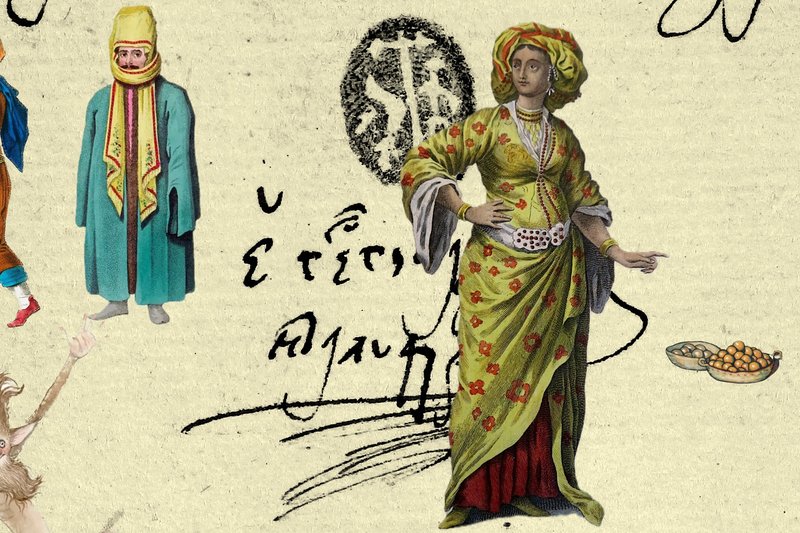

After many days without crossing the city bridges, the Pie-maker stepped outside, aimlessly, to look left and right, to enjoy the snow. She did not know that Murta’s dreams gilded her face, moved upon her shoulders, sprawled across the goatskin draped over her back. Her ișlic hat, beneath a trembling silk sarik, filled with coiled dreams: white rabbits of hope, fruits singing on branches, limbs from another world, hands so long they brushed passersby.

The streets seemed seized by delirium. Seen from windows, the Pie-maker looked like a woman escaped from her husband: her hair loosened, her hat crooked, and beneath her emerald-green coat drifted bitter fumes of despair, leaving behind acacia blossoms.

Merchants pointed her out. Guards blew their horns, shouting that a woman had gone mad and calling for reinforcements to carry her off to Cernica or wherever.

Amid all this chaos on the Great Street and its lanes, one man alone stood petrified: a grocer.

This short, mustached man—destined to remain in history—had spent the night contemplating suicide, for life had lost all meaning. Despite good trade before the holidays, he had discovered that all his money was gone. The chest hidden beneath the floorboards, known only to him, had vanished. Bankruptcy was certain. He could not pay taxes, buy goods, or survive. His only plan was to throw himself from the Colțea Tower that day.

As he stepped out of his shop, perhaps for the last time, he saw the Pie-maker walking down the middle of the street—tall, monumental in her green coat, wrapped in whispers from another world.

The grocer forgot everything. His eyes fixed on the hem of her coat, from which fragile beings emerged in procession, figures clinging to his unanswered questions. And that winter morning, while Murta slept beneath his bridge, satisfied after a night of pleasures, the grocer—standing two steps from his robbed shop—began his adventure as a character. As a hero.

Scenes unfolded before him: his darkened shop, the moon weeping over Lipscani, and in the black mists of a November night from the past, the very thief of his money.

That morning, mysteries surfaced. A laundress learned where her earrings had gone. A boastful guardsman saw the face of his wife’s lover. A confectioner found sudden inspiration. Beneath the columns of Șerban Vodă, a statue appeared resembling the Pie-maker—because a jeweler had misread his oracle. This mistake saved her; otherwise she would have lost her freedom, ending as a merchant’s wife.

All this was recorded in official documents as complaints and chancery reports. The grocer’s thief was punished, losing a hand. The lover was sent to Snagov. The adulterous woman received a string of beads to restore her devotion.

One thing alone was omitted: Murta, lord of dreams, still sleeps beneath a bridge on the Dâmbovița. Only an incomparable aroma will wake him.

Tell me—does anyone still make pumpkin pie, as in the old days?