On a yellowed page I once read about the great faith Oltenians place in enchanted foods. Alongside duck livers, goose fat, and lean meat, they cherish brain—no matter the animal it comes from—believing that any dish made of brain makes you smarter than you already are. Hence the myth of Oltenian intelligence—said to be above the national average, if we consider word density per minute and the ability to live intensely in the immediate past. As for the rest—well, specialists in IQ should be consulted.

One day Saveta awoke struck by a desire whose roots reached deep into her childhood. She had noticed that being a girl was hardly a blessing. No one had ever told her so outright, but it was clear that her father placed little value on her brain; as for her older brothers—there’s no need to go into that. Even her grandfather, more indulgent than the rest of the family, offered her no hope regarding a future she herself imagined as brilliant. For this girl—sixteen at the time of our story—had set her heart on sitting on the country’s throne.

She did not wish to be a princess, nor a ruler’s wife or sister. She had no interest in some minor office. She wanted to become… ruler.

Determined as she was, she began gathering information in great secrecy. Her first and most important observation was that only her brothers were allowed at the table to eat brain dishes prepared in various ways, so that they might become even smarter. Thus she began by studying how brain was cooked. The recipes were many, so she decided to write them down—especially since one of her brothers was already skilled with letters. For months she struggled with writing and gathered recipes. Her favorite was breaded veal brain: on half a page she carefully explained how to remove the membranes, how to slice it thin, how to coat the pieces in beaten eggs mixed with sour cream and grated cheese. The finest part came at the end, when she described squeezing oranges, sprinkling sugar and cinnamon, and finishing with a breath of pepper.

For many nights she dreamed of veal brain, until she could almost taste it. Yet putting the dream into practice was difficult, since in her family women were forbidden to touch brain. Nor did she stand any better chance elsewhere in the city.

But in her dreams—now merging with the dreams of the world—there appeared a shadow, a figure from a mysterious realm. Each time she stood in a dark forest, bats screaming in the trees. A carriage would stop beside her, and at the window would sway the watery silhouette of a man.

So she decided to leave home. Laden with ingredients, with tripod and pans, with everything she needed, she set out one night toward the forest.

Things went well for a while, but—as life is so often unfair—the dish she had dreamed of ended up in the stomach of a bandit.

I will spare you the sad parts. Suffice it to say that this girl, who had a dream and believed in it fiercely, spent several weeks in the forest among a gang of ruffians, until one day she seized a favorable moment and fled.

At the forest’s edge she encountered a carriage exactly like the one from her dreams. It was taking Master Lupu Zidaru to Bucharest.

He was renowned at the time for his writing. He wrote divinely and could imitate anyone’s hand and style. A master forger with a distinguished clientele.

He was the first to listen to Saveta with full attention, without interrupting her, encouraging her to recount even the long nights when she dreamed only of veal brain and the scent of orange peel or hot frying pans. Lupu lived the story intensely, shedding tears alongside her whenever the tale demanded it—especially when it reached the bandits. Saveta, suddenly emboldened, would have liked to describe in detail her weeks in the forest, but the forger raised a finger to his lips. The first thing we must do, he said, aligning himself—without explanation—with her dream, is have lunch.

Saveta entered an inn for the first time—a place she would never forget, with rounded windows and white tables. There she ate breaded brain at last, and I won’t lie: from the first bite, a veil lifted from her forehead. She was still herself, but she saw everything more clearly, understanding at once that a god had placed a hand on her shoulder.

She perfected her writing beside this accomplished artist and soon after was initiated into the occult arts of forgery. Whenever she faltered or made a mistake, she was given breaded brain, and everything became clear again. It was not the food itself, nor its flavor, that mattered, but the spiritual bond with the animal that had lived, seen the world, and harbored its own hopes. There was a force in that bond, one that urged her each morning to rise from bed, shape her eyebrows, slip into velvet shoes, and run to the nearest butcher for a fresh brain taken from a calf’s skull.

Day after day, brain after brain, until one autumn Saveta was able to imitate the princely hand. She had not quite reached the throne she dreamed of, but she signed with full conviction, choosing her name according to the changing rulers—some more pompous, others worn thin by time. Decrees, tax exemptions, letters of recommendation—all could be bought from Saveta for five thalers.

At some point she realized the fortune of having met the forger, a man who had finally lowered his ear to her desires.

In our times she would have been forgotten, but since this was the luminous eighteenth century, Saveta, out of gratitude, took the man’s name. In truth, she had become more than she had ever wished: she could be anyone.

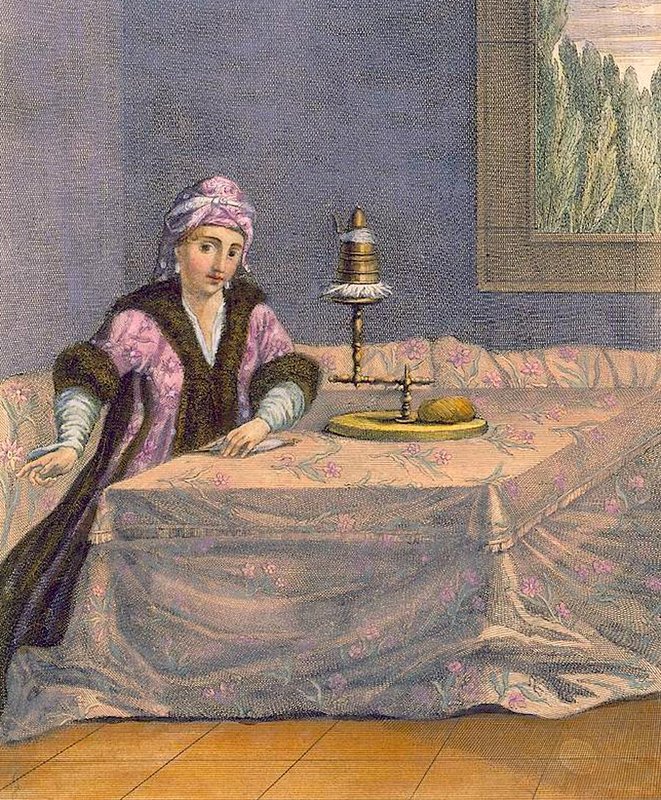

Thus we find her in a court case in 1747, under the name Saveta Zidaru, fined two hundred thalers—not for fraud, as one might think, but for dressing improperly, wearing trousers bought from the Hungarians, and for smoking a hookah in front of the palace.

With this story in mind I went to the Gaudeamus Book Fair, which explains why, instead of chatting about the newly published The Depraved Man of Gorgani, I ended up dancing a waltz—via Shostakovich.