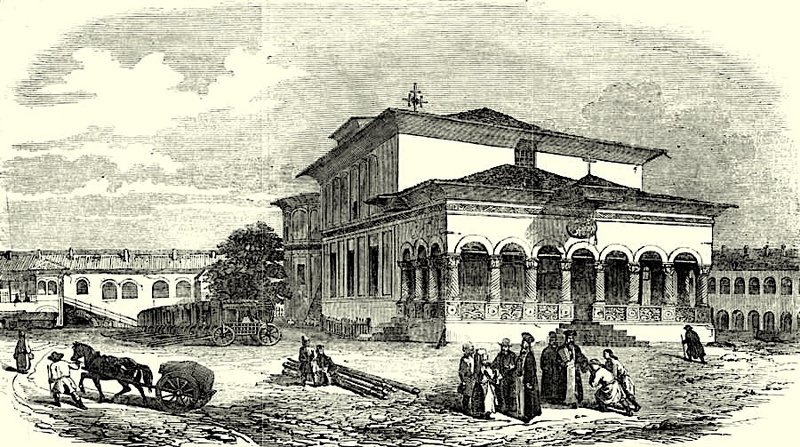

At the Văcărești Monastery lived a young monk named Onisim, remarkably skilled in dealing with people. Gifted with exceptional powers of persuasion, he had been entrusted with collecting debts from the Inn of Constantin Vodă. He moved swiftly and tirelessly, knowing exactly where to find delinquent clients and how to loosen their purses. The inn—located behind what is now the National History Museum—was frequented by small-time merchants and drifters who stored their goods there and then disappeared for weeks, hoping to reclaim them later. Often, this hope proved futile: merchandise went out of fashion, demand vanished, debts accumulated, and the debtors resorted to hiding, petty schemes, or fantasies of a miraculous recovery.

Onisim always found them. He brought them to heel, persuading some to donate their goods to the monastery, others to sell them through ingenious methods no one had imagined before. He knew how to speak, how to make people act. Once, he even convinced a humble corn-seller to parade through the market wearing a blue mantle, chanting a silly song, until he sold every last bead he owned—despite their obvious ugliness.

Every evening, Onisim returned to the protosyncellus with his pockets full. And the protosyncellus, in turn, rewarded him with discreet luxuries. Thus, beneath his monastic robe, Onisim wore translucent stockings and fine Maltese silk trousers.

Life flowed smoothly—until one day, while knocking at a debtor’s door, Onisim heard a voice that seemed not of this world. It was an irresistible call, woven of unfamiliar words. He pressed the handle. The door opened with a creak that felt like the hiss of a serpent sliding under cloth—the premonition of an unavoidable catastrophe.

Onisim vanished for two days. Alarmed, the protosyncellus himself set out to the inn. Following the list of debtors, he reached the door in question and opened it. Inside stood Onisim—naked, wide-eyed, stripped of all words.

He was carried back to the monastery and left in seclusion for many days, his muteness attributed to the devil and his kin. Without Onisim, the inn collapsed. Debtors multiplied, solutions vanished, and soon after came the death of the protosyncellus himself.

Firița had been married young to a timid man, and in a single moment she saw her entire future laid bare. One summer night, as the moon waned, she took the five thalers hidden in the wall and fled. Dressed in her husband’s clothes—baggy trousers, a shirt, a vest, and a cloak made from an old blanket—she entered trade, selling wire brushes from town to town, piled on a cart she built herself.

From afar she looked like a pauper dragging a giant hedgehog. Up close, she stopped people in their tracks: her gaze struck like a blow to the calves, and tiny creatures seemed to perch on her shoulder. She inspired the strange conviction that one had finally met a new Messiah.

Eventually, Bucharest held no more mysteries for her, and the Inn of Constantin Vodă became her home. Until the day Onisim came knocking for money.

Their encounter struck like a blow to the forehead. He stood frozen, stunned by her presence, by the translucent stockings beneath his robe, by the shared talk of fine fabrics and foreign goods. Two days and nights followed, in which Onisim fell into sin and Firița reassessed her freedom.

His muteness came at dawn, when the door opened and the protosyncellus appeared, umbrella in hand. At that moment, Onisim lost his voice forever.

They never met again. She did not seek him, unaware of the mystical impact she had wielded. He did not seek her, having lost both his voice and his faith in rhetoric. Their bond was reduced to those two eternal days—preserved here, and now, in your thoughts.