Late April, 1798, just after Easter, as now. From a princely nizam we learn that a locust invasion is being announced. Still small and easier to exterminate, the locusts had begun to advance slowly from Focșani toward Bucharest. People grew alarmed. Hangeri ordered measures to be taken and dictated a document stating that the situation was extremely grave. As the first and best measure, the relics of Saint Michael the Confessor—also known at the time as Sinadul, since he had been bishop of Synada—were to be brought to Bucharest.

The saint, celebrated on May 23, rested at Arnota Monastery, in Vâlcea, and whenever necessary, his earthly remains, kept in a gilded coffin, were placed in the monastery’s carriage and taken wherever they were needed. In this case, to drive away the locusts.

It is true that at the end of the document Hangeri—son of a physician and educated in a more secular spirit—also recommended resorting to other means for killing the locusts, “now, while they are still small.”

The letter was carried swiftly to Vâlcea, read by the abbot (for it was then a monastery of monks), commented upon by the chancellery, and finally a monk was summoned—apparently the youngest in the monastery—and sent with the relics to Bucharest.

Thus, today’s event unfolds at the pace of the carriage, from Arnota to Antim Monastery, where the first stop was to be made.

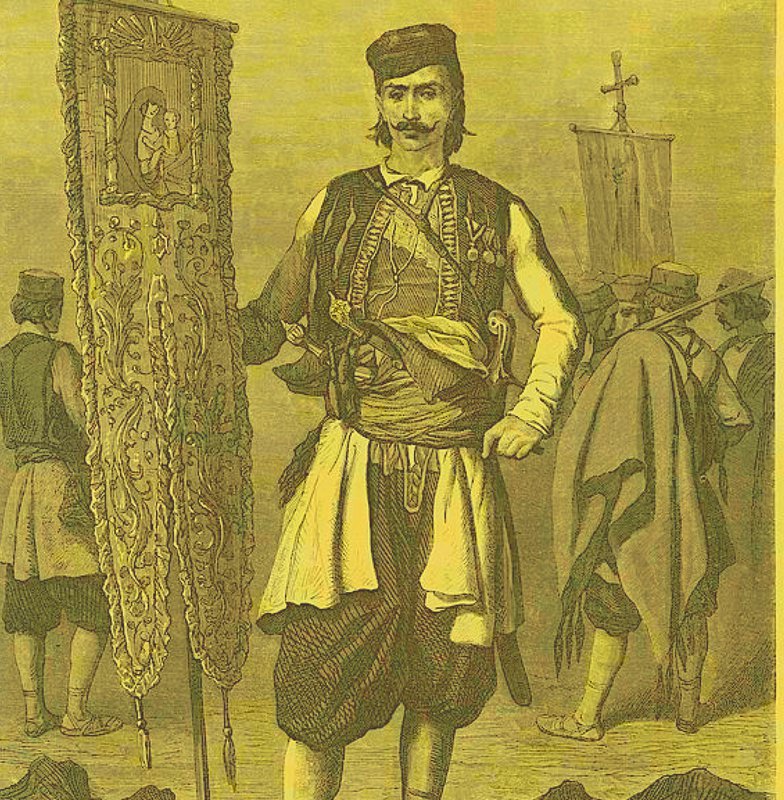

The relic-bearer was sixteen years old and named Damaschin. His monastic life had begun two years earlier, when, at the advice of his parents and brothers, he had entered the monastery “with the Greeks,” having heard that the food there was good and plentiful.

Damaschin entered Bucharest at midday. Picture him: dark-haired, rather short, wearing a brand-new comănac, in whose lining he had sewn wormwood to protect himself from temptation.

Around Gorgan, the little carriage got stuck in the mud. He got down, and at a short distance the market opened up, with garlands of flowers, baskets filled with painted eggs. People—more than he had ever seen in his life: floral skirts, carts with demijohns and long-necked bottles, round tables laden with appetizers, bowls of roe and olives, fresh curds and greens, and even a tree hung with smoked bones and meats that had been cured for a long time.

Damaschin had never seen so much movement or so many unimaginable things, and he stood gaping, forgetting for a moment about the locusts, the relics, the important mission entrusted to him.

When he finally came to his senses, he asked someone to help push the carriage—but it had vanished without a trace.

Naturally, he began to wail, to explain the importance of his mission, how the locusts would arrive any moment and devastate everything. The residents of Gorgani pitied him and, reasoning that relics could not simply disappear, began searching. But as Damaschin followed cart tracks and searched for the horses, he discovered other faces of the city. First he drank a coffee flavored with vanilla and orange peel. Then someone led him into a tavern, where he was given spicy sausages and pickles, which he had to drown with an entire pot of wine. Dazed, his comănac askew, a tuft of hair escaping at his temple, he wandered through several streets, continuing to lament his fate.

When he reached the House of the brothels—you know, the one in Gorgani I spoke about in Homeric—his legs refused to obey him. The whole neighborhood knew his story, and there was no one who did not promise to look for the bones of Michael the Confessor, the terror of locusts.

Evening came. Bucharest slept without worry. Damaschin discovered the pleasures of the flesh. To console him for the loss of the relics, the mistress of the brothels invited him into the fountain with jets and roses, and after a warm bath he learned the softness of divans and the caress of princess-like fingers.

The next morning, when the sun rose, when gates creaked and carriage wheels were heard again, the city’s gardens had vanished. More precisely, only the old trees remained standing, since locusts eat only young leaves—preferably shoots and buds.

Damaschin traded his cassock for colorful șalvari, remaining forever a libertine in the House of the brothels, and in secret he fashioned himself an altar, where each evening he lit a candle for the tribe of locusts.

The relics were found one morning on the steps of Antim Monastery, and life returned to normal. Well—not entirely, if we consider that the next invasion found the people of Bucharest prepared with curtain-traps and ditches in which many locusts met their end.