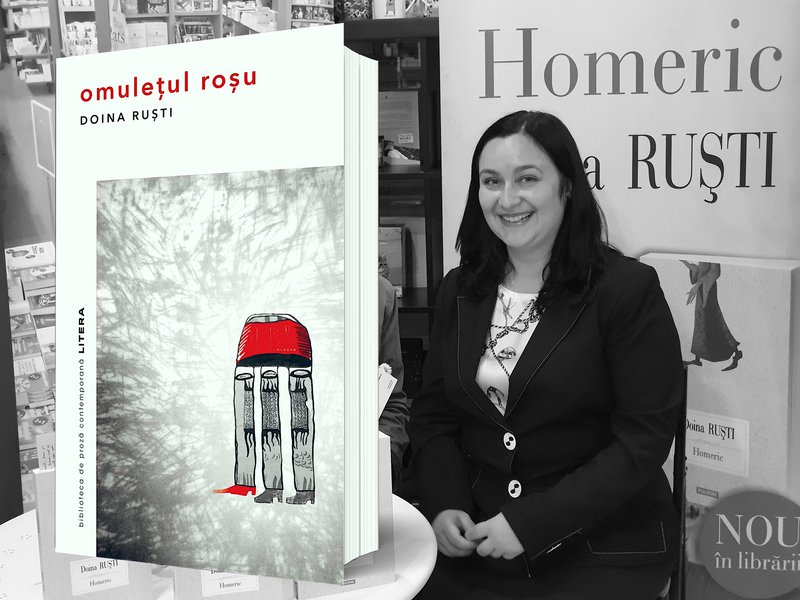

“Omulețul roșu, Doina Ruști once said, is a literary manifesto.”

Reading it again recently and attempting to mentally reconstruct the atmosphere of its debut (in 2004), one realizes that the novel illustrates with remarkable clarity the theoretical premises of the early 2000s, when nonconformism took on two main forms: an almost indecent autobiographical exposure and an explicit revolt against traditional epic structures. Without resembling the dominant prose of its time in any direct way, the novel nonetheless represents—at least in spirit—the era and its aspirations.

What is truly astonishing in this novel is its capacity to narrate from so many perspectives. At its core, the story follows the path taken by most prose writers of the 2000s: an account of everyday reality, socially bleak, excessively subjective, presenting the experiences of a narrator closely resembling the author. Yet Laura Iosa, the novel’s narrator, is endowed with a complex personality: she is a strong character, driven by imagination and passion. She is fully involved in everything she does, evolving throughout the novel in a convincing manner, oscillating between the cultural life of Bucharest—where the future appeared uncertain—and the inexhaustible realm of the imaginary, here called alazar. Even had the novel stopped there, it would still endure.

But Doina Ruști projects the story into a multitude of sequences without losing anything of the overall epic. This is also noted by Roberto Merlo in the preface to the new Romanian edition (Litera, 2021).

At the center lies a word—an obsession I later rediscovered in The Phanariot Manuscript (2015)—a linguistic unit capable of generating multiple narratives:

“Words are blue bees—Naum was right. You have no idea how many aspirations cling to their little legs, how much life howls, trapped in a vibration!”

As repositories, words possess both an extensive history and a private life:

“Some words are forged with difficulty, out of tremors accumulated over a lifetime, and in the end, once they have fully entered common usage, they decay. A sinister howl falls upon them, shattering them to dust. And so, damaged, they are sometimes preserved… Why would someone preserve them?”

Around this vision, the story unfolds ingeniously and, I would say, originally: a software developer creates a virus and sends it to an unknown woman whose voice he once overheard during a phone conversation. This explorer, Albert, seeks to conquer a territory and sends an email containing the virus. The intriguing part is that Albert’s virus resembles a Trojan horse. Inside it are words, phrases, images capable of manipulating Laura Iosa’s aspirations and imagination. As a collateral effect—through an accident largely linguistic—the Little Red Man is born, becoming both narrator and active participant in the present action.

The story, however, is not told in this order. The novel’s charm lies precisely in its sinuous storyline, twisting along the paths of an infinite universe. Laura’s present experience intertwines with Albert’s story, recounted by the Little Red Man, while additional narrative layers gradually emerge through the comments of internet users, each with their own life and epic trajectory. Gradually, before our eyes, a story with multiple “drawers” is written—as the novel itself suggests—each belonging to a single biography, Laura’s.

Instead of a linear narrative in which the character lives through dozens of nearly identical days, The Little Red Manintroduces us to a complex universe dominated by an optimistic sentiment, sometimes even in spite of dramatic events.

Doina Ruști’s characters—both in this early novel and throughout her work—are prototypical: they linger in the memory like Flemish portraits that instill an irrefutable sense of reality.

Albert’s biography unfolds against the backdrop of late communism, followed by the shock of the Revolution and the transition to what was called “wild capitalism.” Nearly all characters harbor obsessions rooted in the communist experience. Rufă, the son of a former secret police officer, becomes Laura’s correspondent. Their relationship is particularly interesting as a historical projection of individuals just emerging from communist depression. Laura writes a confession and sends it by email to several men. One of them is Rufă, a psychiatrist who does not know the sender’s identity. In everyday reality, the two are neighbors, frequently encountering each other and mutually despising one another. Yet in the shadow of anonymity, a dialogue grows between them—one impossible in real life.

Both characters have lived through trauma, having lost a parent under dramatic circumstances. Both carry the burden of dictatorship. Symbolically, their correspondence expresses the essence of totalitarianism: their neighborly relationship manifests metaphorically in the novel, where all of Laura’s experiments—from her job as a cook to her adventures in alazar—exist in permanent dissidence. This dissidence ultimately means the dismantling of authority:

“Authority! What a crumpled word! I mean everything that moves under the guise of boss. The super-organized gang of activists turned businessmen, bosses, politicians, governors, officials with decision-making power, parliamentarians. And parents. Especially parents! I don’t know what’s worse: being screwed over by the ruling gang or by parents—cruel, indifferent, suffocating, ready to push you in one direction or another…”

The alteration of authority—arguably the novel’s central theme—returns obsessively. Albert’s parents are indifferent, a story completed by the histories of other characters, particularly the forum users commenting on Laura’s confession. Most vividly, however, the theme takes aesthetic form in alazar, where Laura enters the life of a family petrified by educational stereotypes. Nearly every character has a microhistory of their relationship with family, culminating in Mrs. Luminița, the cannibal teacher of alazar, who grows monstrously over the classroom—a deformation of weakened authority.

As many have noted before me, The Little Red Man foregrounds an enchanting story that deepens into the territory of complex meaning. “The novel has two qualities,” says Marco Dotti, “depth and the beauty of storytelling.”

In the foreground is Laura’s story, described as “outraged femininity” (Dan C. Mihăilescu), socially rejected. She holds a degree in classical philology yet must work as a cook for a family—a premise that immediately generates empathy. Her online searches, the discovery of the internet’s boundless possibilities, virtual love—all serve as gateways to a story that continually ramifies, ascending toward the realm of continuous creation.

Any human manifestation, no matter how insignificant, sketches a territory that develops autonomously, as in one episode of alazar, where a hastily written sentence falls into an abyss and becomes the backbone of a man, then of all his descendants, until one of them releases it—written in red letters—toward its true addressee, above their world.

This episode—the preservation of a message across generations, the image of people as containers, the existence of a predetermined (yet unmanageable) trajectory—encapsulates the novel’s spirit and message. The Little Red Man is a book about storytelling in all its meanings, and about the varied, sometimes hypocritical ways reality becomes literature.

“There are thousands of faces I have looked at in my life that entered my brain without my noticing them, without knowing anything about them, and stayed there, untouched, in the subconscious, in the database, in the deepest drawer…”

This observation, belonging to Laura Iosa, materializes in the space of alazar, a kind of narrative matrix—the birthplace of the Little Red Man, a vortex over which its creator has lost control.

The novel operates across multiple levels of reception and expressive registers. It begins classically, in the first person, later supplemented by forum dialogues and a poem inspired by a secret layer of the main story. There are thematic micro-stories, an epistolary component (Laura’s), confessions, online discussions—yet the global vision is never lost.

Symbolically, the novel ascends from a satirically portrayed real world—corrupt, aggressive, decadent—toward the imaginary constructions of alazar, without the neo-gothic note becoming dominant. As Il Libero writes, “a talented writer, Doina Ruști parodies noir fantasy.” The Little Red Man, as a cyber-apparition, anticipates Zogru (from Ruști’s next novel), emanating the same indulgent acceptance of the fantastic.

The “dystopian vision” and “fresh style” noted by Noemi Cuffia stem from Ruști’s ability to deploy erudition with utmost discretion, dissolving it into every layer of the novel. A story is a construction that brings past and future together, leaving in the foreground the living life of a city.

As La Stampa observed, “the novel is read with great pleasure: with a mind shaken by exclamations and with barely restrained laughter.”

Far from exhausting the extraordinary resources of this novel, I conclude by aligning myself with La Stampa’s observation that The Little Red Man offers both stylistic freshness and emotional force—stemming from Doina Ruști’s unmistakable voice and her ability to manage vast epic material and fix it into unforgettable sequences.