It was the year 1782 — imagine it: full of colors and the smell of ovens. An early Bucharest summer, with sweating silks and blooming linden trees.

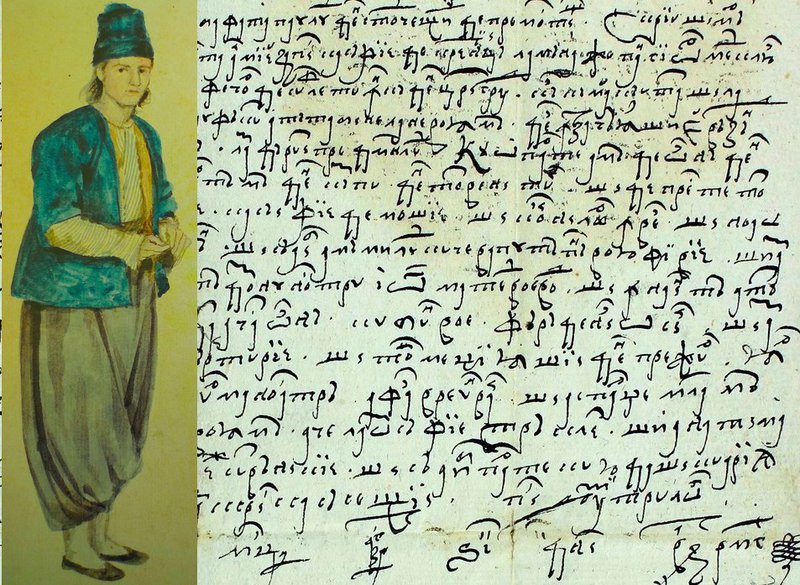

A student had just left Saint Sava School — roughly where today’s University Square lies — dressed in a brand-new anteriu, proudly wearing a purple fez and light-colored slippers. He walked past the school’s botanical garden, trying to remember the scientific name of the dandelion, passed the cemetery — today the Russian Church — then took the narrow streets toward the Rag Market, behind the Princely Court, where a newly opened grocery shop stood.

And what couldn’t you find there! Turkish delight in small wooden boxes painted with flowers and cats, little barrels of syrup, pastries laid on reed trays, to say nothing of cured meats, cheeses, bowls of fish roe and olives, or braga, drunk on the spot from crystal glasses.

But on that day, the student with the purple fez — nicknamed Dănache by his acquaintances — cared about none of this. He was gloomy, dark-minded, truly miserable, because his teacher had been making his life unbearable.

The teacher was tall, with an arched nose and arrogant eyes — half Greek, half Bulgarian, his mouth full of ts and tzsounds, and Bulgarian curses. As soon as he sat at the lectern, he would search the room for Dănache. No matter the subject, the first questions always struck him. And for every mistake, there were punishments: memorizing the aorist, the entire verbal paradigm, in a language that was not yet dead then, but which today has become a revered corpse — endlessly quoted, with a certain pride, because there’s no one who doesn’t like to flaunt a surviving Greek word or two. Anthropos, agapé, sometimes even paideia — relics carried piously in the breast pocket.

But Dănache — whose only joy lay in his flashy fez — simply hated the aorist. He despised periphrastic constructions and the passive voice. He didn’t want to speak Greek, nor become a deacon, a clerk, or any other pen-pusher in a chancellery. His dream was to do nothing. And if he had to do something, he would have settled for keeping accounts in a market or opening a grocery shop, just like this one.

While shadows of his Greek teacher’s silhouette passed through his mind, a woman entered the shop — a young lady, her headscarf artfully tied above her ear, with eyes that made you forget your own name. Ignoring Dănache, who stood there open-mouthed, she asked for two drams of săricică.

What could such a woman want with săricică? Surely not to poison rats! Just looking at her, Dănache imagined dark figures — men and women, perhaps even children — shadowy people, beasts and thugs. And as the faces of future victims multiplied in his mind, the familiar, horrible face of his Greek teacher slowly took shape among them. Loghiotatos, as he was called.

A thin thread grew in Dănache’s heart, eventually binding him forever to the beautiful buyer of săricică.

The next day, on Saints Peter and Paul’s Day, he placed on the teacher’s desk a porcelain plate — specially brought for him — holding kataif garnished with pistachios and just a trace of poison.

Bucharest was outraged. News of Dănache’s deed spread from one end of the city to the other, while Isac Ralet summoned the doctor — a young man educated in Pavia. Carried from hand to hand, the teacher — who had already taken a step toward the other world — was passed through the gaze of the neighborhoods, from Saint Sava to Colțea. Many who had never even known the professor remained leaning against fences until evening fell. And because it was summer and cherry season, for many years afterward people felt compelled to retell the dramatic day whenever cherries ripened.

Dănache repented at Căldărușani Monastery, where he remained forever — exiled and subjected to rigorous re-education.

As for the teacher, it must be said that although he survived the poison, he lost his passion for teaching. Along with that June day, the small fez of a student remained forever stuck to him — a reminder of how Greek grammar can turn a boy into a beast.