Today I am resuming my blog in Adevărul with a story told in two ways: written on vellum paper and narrated aloud in Litera Mov—about a monastery with a historic name.

In a document dated 1794, I came across an incident that took place within the precincts of Balamuci Monastery. It is true that an asylum was later established there, but that happened some thirty years afterward. At the time I am referring to, the place was still called Holy Balamuci Monastery, as the document states in black and white. There is no mention of madness, disorder, or chaos.

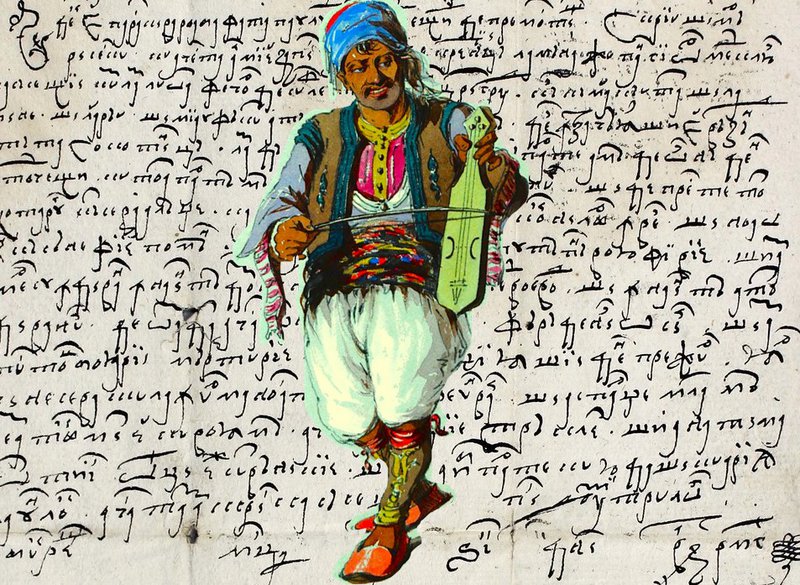

The incident involves a monastery fiddler named Anastas—we can safely call him Tase. A young man and a fine musician, he occasionally earned extra money by playing at weddings, but only after completing his daily duties: hauling water, tending the monastery’s animals, working in the vegetable garden, and performing music at religious feasts—Christian celebrations, of course, on major feast days, commemorations, or solemn gatherings.

Tase belonged to the monastery, along with his family: a father, also a musician, and a wife named Stoica.

We know a thing or two about fiddlers. They were a special caste, respected according to their repertoire and, above all, their speed in spreading news. Fiddlers—especially those attached to boyar households—moved from gate to gate, singing the latest events: who had married whom, who had died, which boyar wore what on a particular day, or what goods had arrived through Lipscani.

Tase was not quite such a fiddler. He lived in an isolated monastery, somewhere beyond Ștefăneștii de Ilfov, between Grădiștea and Fierbinți. He was a slave and worked hard. Yet being an artist, he cared deeply about appearances. He wore trousers tightened below the knee, a vest made from a former priest’s cassock, and in an inner pocket he kept a tin watch bought at a fair. His fez was adorned with a delicate scarf, a wedding gift. And there was something else: though he went barefoot most of the day, when he played music he put on red slippers sewn by Stoica from scraps of broadcloth.

This Tase is today’s protagonist: young, gifted, and unlucky.

On Saint Nicholas’ Day, the monastery’s feast day, after the incense, the chants, the meal, and after the guests had left, Tase—the talented singer and slave—was killed.

The document provides many details, supplied by the killer himself: Father Vasile.

Alongside the abbot-archimandrite, the monastery also had a particularly sensitive priest. He lived with his family in a house near the monastery gate. He loved music and would sometimes listen to Tase, freezing in an inexplicable pain or sighing without reason. (Never believe, by the way, when someone says there is no reason.)

On that December day, after the feast had ended, Tase walked toward his shelter at the far end of the monastery yard. Father Vasile loaded his musket and fired a shot—not in madness or anger, but to honor Saint Nicholas and his grace.

By misfortune—one might say piously—Tase lost his life.

Though it was an accident, Father Vasile could not be considered entirely innocent. He was sentenced to provide Stoica with a full set of clothing and to pay for all memorial services for the deceased for three years. And, of course, he was required to purchase another slave to replace Tase, so that the monastery would not suffer loss. We learn on this occasion that religious services were not cheap: since Tase was a common man, as the document puts it, his memorials cost only sixty talers per year. So the priest tightened his belt a little.

The dead man’s family accepted the settlement. What else could they do, being slaves of the monastery, while the killer was—after all—a priest.

What the document does not record is the true order of events and their deeper causes.

Vasile listened to Tase’s music and was carried far away, into the gardens of his own suffering. For without ever speaking of them, every person has such gardens—private parks in which they wander alone: neglected paths, muddy alleys, sunburned bushes with nibbled leaves. It is there that one goes to cry when struck down, when denied what one desires, when adored people turn away, or worse, when hope itself disappears.

That was where Vasile was. And the doomed slave’s song plunged him even deeper. Every sigh, every inflection twisted the knife further in the wound. Listening to Tase became unbearable. Without realizing it, he reached for the musket—and the rest you already know.

And a fiddler scraping his violin, a snot-nosed boy from the neighboring village perched in a mulberry tree, understood then that even being too talented can be dangerous.