In the spring of 1793, several documents were drawn up concerning a sealed apartment in the Inn of Prince Constantin. Eight months earlier, a plague victim had died there, and as a sanitary measure the rooms were closed. The order came from the epistat of public health—a captain with soldiers under his command, named Panait. Health, in all eras, has been enforced at sword point.

The inn stood roughly where the National History Museum is today, on Victory Road, set slightly back from the street. Built by Brâncoveanu, it was imposing for its time, modeled after Prince Șerban’s Inn: columns at the front, shops on the ground floor, and behind them two levels of rooms opening onto wooden balconies, where many had carved their names. At the time of our story, the inn was administered by the Văcărești Monastery. One of the monks in charge of revenues petitioned the Divan for permission to break the seal on the apartment door.

Months earlier, in June 1792, Ienache Corei-Bașa arrived from Istanbul, dusty and with little luggage. He was a small, dark-skinned man, described repeatedly as poor, without money or valuables. And yet he did not lodge in some marginal inn, but rented two rooms in Brâncoveanu’s—expensive, if not exorbitant.

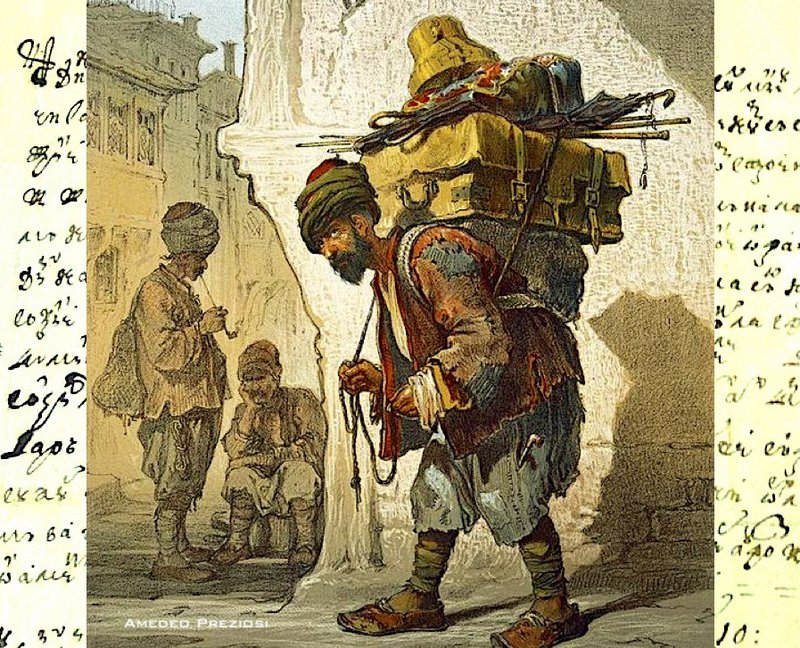

Ienache was a minor money-changer, a guarantor, and sometimes a keeper of traveling merchants’ goods. This explains the two rooms. Being responsible for guarding chests of beads, brooches, mirrors, and cosmetics, he held a position of trust. A bașa—a chief. You can picture him: grave, open-faced, decent, inspiring confidence at once. In the evenings, peddlers knocked at his door to leave their goods for safekeeping.

Most had chests that unfolded into market stalls, some carried by straps across the chest. The owner’s name was visible—painted boldly or discreetly carved into the lid. Small trunks in every color, locked, some with golden clasps, others wrapped in cloth and reinforced with nails and tacks. Amid this clutter of wares—knives, lace collars, wigs, gloves, rings—lived Ienache Corei, known as Bașa.

From this modest enterprise, he hoped to accumulate capital and return to Istanbul, where his wife and children waited. Judging by his name, he was Greek—perhaps Aromanian or Meglenitic—but certainly a Romanian speaker, having traveled often to Bucharest.

That June, when the lindens were blooming, shortly after his arrival, the newly established chief of the trifle-keepers died. A doctor was summoned, as was Captain Panait, guardian of the city’s health. It was established that Ienache Corei had died of plague, alone among the bundles.

His body was taken to Dudești and thrown into the lime pit. The apartment was sealed. The small traders lost their goods; the inn lost its rooms.

Months passed. Toward the end of March, a prudent monk, concerned with monastery revenues, bought himself a new silk-trimmed cap, bathed, twirled his umbrella, and knocked on Panait’s door. Permission could not be granted until the dead man’s relatives were found.

By evening, a certain Iordache Țino was identified, related to Corei’s wife. No documents proved it, but his word carried weight. The trifle merchants gathered, hoping to recover their beads and valuables locked in colorful chests.

Panait wrote to the Palace. His letter survives to this day, examined from every angle. Eventually, responsibility fell to Vornic Scarlat—the one man Prince Moruzi trusted without reserve. He was tasked with disinfecting the plague room.

Vinegar was poured. Walls scrubbed with wormwood soap. Clothes boiled in cauldrons until lace collars and silk scarves disintegrated. Floors were scoured with wire. Every chest washed, smeared with petroleum, left outside overnight. Windows stood open for days. Braziers were brought in to dry the walls. Throughout, Scarlat took meticulous notes, knowing how precious such details would be to someone like me.

Finally, after a fresh coat of lime, the peddlers reclaimed their goods. Țino received his promised grain.

As for Corei-Bașa’s family—they had perished long before, cut down by the same plague the ingenious guardian had brought to Bucharest.