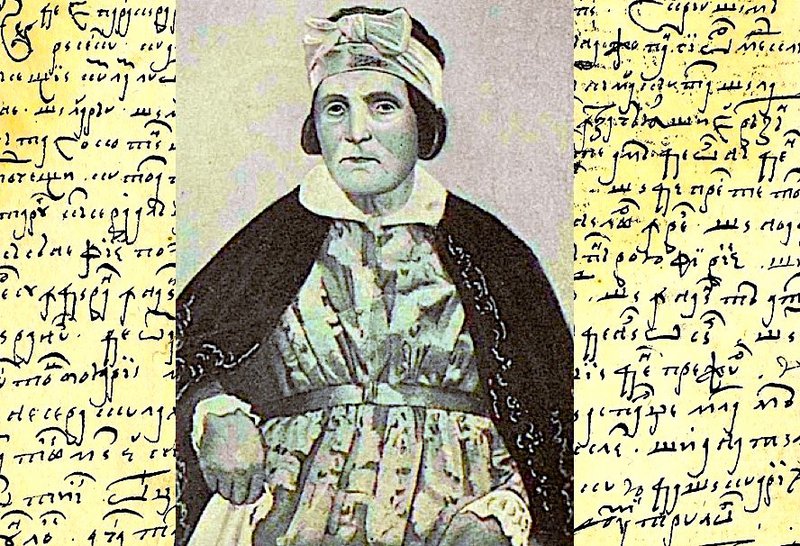

Some years ago, I published a document about Ciptoreanca—later transformed into a character in Homeric—a woman who, through her will, freed several slaves. Among them was a girl named Voica Chițeasca, whom she considered her child of the soul. She endowed her generously and married her off to a free man who ran a small trading business in Bucharest. Only recently did I come across two documents that place Voica once again at the center of events. It was an unexpected and oddly sweet encounter—straight out of a soap opera.

The same Chițeasca, freed from slavery with great difficulty, now found herself in serious trouble. The year is 1793, and Alecu Moruzi sits on the throne of Wallachia.

In the meantime, Chițescu had left her. Chițeasca was left with nothing but the name and a child already grown—a daughter of marriageable age. Her fortune had vanished.

Her story reveals how people who escaped slavery managed to survive. Voica—also called Voichița or Chița—married as Chițescu, had once possessed some property, which her former mistress had carefully protected, reinforcing it with documents proving that Chița had been among the slaves inherited from her parents, and thus fully under her authority—including the right to grant her freedom. Chița was emancipated at the time of her marriage and endowed with a house and all necessities. In 1784, when Ciptoreanca drew up her final will, Chițeasca already had a child—a daughter—and was married to a free man, explicitly described as a Romanian.

The new documents I recently read, published by V. A. Urechia, date from 1793. By then, Chița’s daughter was nearing marriageable age, and Chița herself was already considered “past her youth”—meaning she was likely no more than forty, and her dowry had long since dwindled.

This former slave moved within a world of market women, petty brokers, commission agents, corn-meal sellers, itinerant vendors of trifles—small-scale entrepreneurs involved in soap and candle contraband.

Abandoned by her husband, she befriended a bead seller named Nicolae Stanciu, about forty years old, like herself. His trade prospered. The value of brides was measured in strings of beads—especially large pearls (ormuze), but also glass beads, silver ones, beads with gold links, gemstones mounted in metal (particularly emeralds), amethysts, long strands of amber, and other items brought from the East via Istanbul. A bead seller either rented a table inside a shop or wandered from door to door with his bundle slung over his back. It was a good trade—steady, modest, but reliable.

Nicolae gained Chița’s trust. But instead of asking for her hand, one night toward the end of August he ran away—with her daughter.

The blow was devastating. Chița filed a complaint at the Palace. Remarkably, the ruler was genuinely moved and immediately ordered the kidnapper’s arrest, which was carried out a few weeks later.

As we know from another case, the punishment for abduction without weapons—especially when the girl consented—was severe. There were, however, two possible resolutions: either the abductor married the girl, restoring social order, or he was punished—forced to pay compensation or shaved, beaten through the marketplace, and exiled, after having a hand cut off.

By October—much like now—Nicolae awaited his sentence, imprisoned in a cell at the Criminalion, in the basement.

The continuation of the story appears in a second letter Chițeasca writes to the ruler, in a tone that astonished me—almost fraternal. She first informs him that she has reconciled with the bead seller, then explains further: the girl has already “fallen into acts of fornication” and will be difficult to marry off. On the other hand, Chița confides, it would be improper for her daughter to spend her life with the man who abducted and corrupted her. From her perspective, the bead seller must accept the position Chița had offered him from the very beginning.

Thus, through a formal act, she appoints him the girl’s guardian.

What did this entail?

Nicolae, the bead seller, was now obliged to work hard and gather money for the girl’s dowry. Naturally, he was no longer allowed to see the girl. But by virtue of his position, he had ample opportunity to see the mother. More than that, it was also his duty to find a suitable husband for the girl. Chița insists on this point, specifying that her daughter needs an honorable man “of our standing”—someone rather better than a poor bead peddler.

The former slave knew her worth. She had traveled a hard road to her current social status, fought in court against heirs of her former mistress, endured much. Money alone did not interest her; she wanted to preserve her standing in the neighborhood. And on top of that, she wanted the bead seller under her control. To ensure this, she asked the ruler to sign a document stipulating that Nicolae could be judged again should he fail to keep his word—lifelong obligations.

The ruler granted her request. And to add his own contribution, he sentenced the bead seller to donate five hundred talers to the “box of mercy.”