January 1794. A man lies in the snow, dressed only in his shirt. The authorities are alerted; people gather as if for a spectacle. The man, very young, is named Radu. About three weeks earlier he had left Gheboaia (Dâmbovița County) to spend the holidays in Câmpulung, at his sister’s house.

And oh—how he had prepared! Ever since autumn, from the first heavy rains until the drizzle set in, he had been constantly on the road. A small man, bent under the weight of the bundles he carried on his back, he wandered through markets and fairs, selling flowered mugs, pitchers, and painted bowls—the latter his true favorites. He was a potter and painted his wares with real talent. He owned a kiln by the banks of the Ialomița River, and on summer evenings one could see a ribbon of smoke drifting across the water.

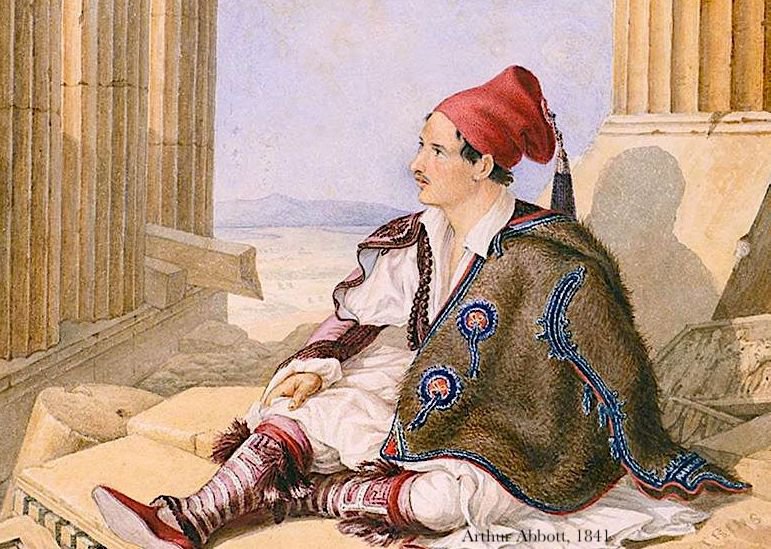

For years now, Radu had carried his fragile goods on his back, and with the money he earned he bought clothes—each time something unseen before—being especially fond of collars and tassels. I imagine he must have looked rather like the figure painted by Abbott (see above).

For reasons unknown, in Gheboaia—Gheboaia being what it is—not a single girl paid him any attention, because Radu belonged to that category of men who try too hard. And let me tell you this: nothing is more damaging to a man than effort. It strips you of credibility, as they say. Naturally, this time too he had tried enormously hard, because a girl from Câmpulung, with almond-shaped eyes, had caught his fancy, and by Christmas he was determined to attract her attention.

First, he found a slightly stiff greenish silk from which he made himself a fermenea, a short jacket. To ennoble it, he added a rich collar, pressing the tailor to sew a thick cord along its edges—a decision that ultimately proved rather unfortunate. But without any ornament, the collar looked flat, failing to highlight the beauty of the fabric. The tailor suggested a small yellow ruffle. Radu felt that now he truly resembled a pheasant. In the end, he sewed on a purplish fringe himself, doubled with lace, which he believed lent him an air of elegance. He lost almost a month on this garment. But no one else had anything like it. And he wore it open, so that the beads—worth the price of two bowls—could be seen.

He bought his anteriu from some hawkers: long, striped, made of linen and silk, ornamented with a belt that looked coarse at first glance but was full of secret pockets. He spent weeks searching for footwear, but it was worth it—he found boots never before seen in Gheboaia, ankle boots with German buckles. Finally, the hat also gave him trouble, for his money allowed few choices. Still, it was new: red broadcloth with a silk tassel. Over everything, he wore a thick woolen cloak fitted with a hood, in case a blizzard should strike—God forbid! And here I must tell you that this boy from Gheboaia always traveled per pedes, on foot. Today, a car would take about two hours on this route (at 60 kilometers an hour): through Târgoviște, then via Voinești, and you’re there. On foot, especially in winter, it could take a day and a half—but Radu was trained by years of trudging from fair to fair with his bowls, so if he set out before dawn, he would arrive the following night.

The Christmas days in Câmpulung passed the way winter dreams do. His sister showered him with gifts and introduced him to the neighbors. Several women praised his lace collar, and on New Year’s Eve Radu danced for the first time in his new boots. And to complete his happiness, the almond-eyed girl persuaded him to extend his stay until Saint John’s Day. Though they did not speak much, she noticed his clothes, showing particular interest in his belt, the hidden pockets in its lining, and above all in what he kept there, among his small treasures. Her dream was to become a high-end dressmaker, and as he listened to her, fine drops of liqueur seemed to gather on Radu’s eyelashes.

At last, sensing that people had grown weary of guests, he set off for home on the ill-fated day of January 11 of that year. He was now laden with gifts and food, and had even taken along a flask of well-aged plum brandy. He moved with difficulty, and the road, as on his way there, was deserted.

After passing Voinești, he encountered some men who had only recently chosen the profession of thieves—the Bratu brothers, from Câmpulung. They stripped him first, then took all his belongings, and because he began to recount how hard it had been to find those boots and how much he had worked to save the money, the Bratu brothers beat him. They tortured him badly, the document says, and that is why he lay in the snow.

That is how some servants found him, and the Great Spătar, deeply moved, wrote the entire story to Prince Moruzi—a letter that has come down to us thanks to V. A. Urechia, as usual. The ruler ordered that the culprits be found and punished severely.

A posse was formed; the Bratu brothers were hunted through the forest. It was winter, the snow hard to cross.

Only by Saint Mary’s Day did Radu dare visit his sister again—but the almond-eyed girl had long since disappeared from Câmpulung.

The Bratu brothers were never caught. It was rumored they had fled toward Vienna, where they had opened a business selling clothes and other fineries.

If you ever pass through Gheboaia, know that people there still make painted bowls today, and among petals and blue feathers, one can still glimpse almond-shaped eyes.