Toward the end of the eighteenth century, there lived in Bucharest a doctor, half Greek, half Aromanian, by the name of Giorgiache Sculida. He was short, restless, dark-skinned, and above all addicted to movement. He examined his patients on the run, diagnosing them at a glance, then rushed to the Palace, where he had many connections, scribbled a prescription for the ruler, and immediately afterward threw himself into his carriage — always accompanied by Elisabeta, the servant, and by the same perpetual luggage that amazed the whole city: two gilded trunks and a scatulca— a small hand-held casket meant for keeping valuables.

The coachman cracked his whip, and the carriage, flanked by six arnauts, set off toward Nicopolis, where the doctor kept a second residence.

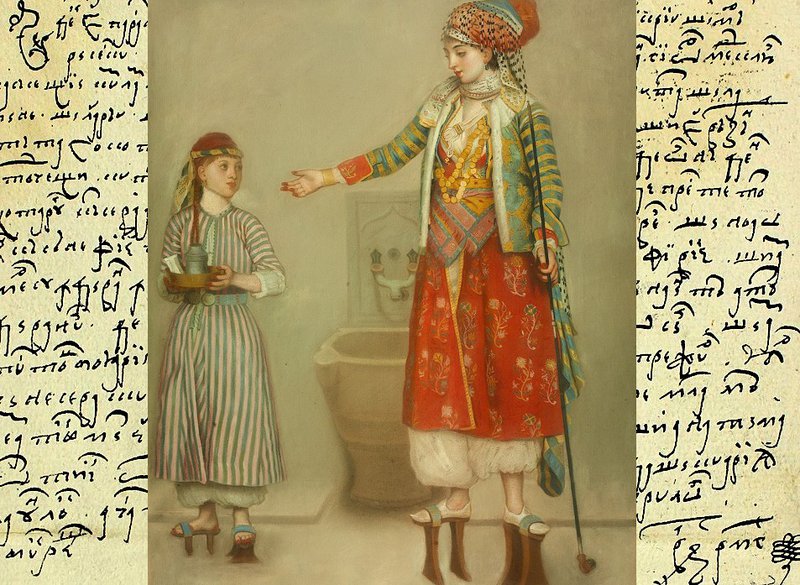

A widower, with children and a servant — that was his life. The children, five in number, were already adolescents: four boys and one girl, named Zoe. Elisabeta had initially been hired especially for Zoe, to teach her how to become a woman — to sew, to wash, and to walk on short wooden stilts worn in Bucharest when the rains began and the streets turned to mud. These wooden pattens were used to protect shoes, as in the painting above by Jean-Étienne Liotard, who, as I mentioned before, spent some time in Iași precisely during the period we are discussing.

Once Zoe had learned everything Elisabeta knew, the servant took on other duties, as happens in the household of a doctor who travels constantly, until, in time, she became a kind of shadow of Doctor Sculida, who never went anywhere without her. As she would later write in a complaint, she had become his right hand.

The children followed in their father’s footsteps, being just as restless — even more so. The eldest had secretly taken a post as a secretary at the Orthodox Patriarchate in Constantinople, while the others, the boys and Zoe, visited him often, eager to see what was then the capital of the world. Torn between Nicopolis and Bucharest, they carried adventure and the dream of great discoveries in their blood.

Because the doctor lived in constant motion, the people of Bucharest nicknamed him Fârțogu — “the Restless One” — and the name stuck so well that even official documents recorded him under this sobriquet.

Elisabeta, content with her role and fully trusting Fârțogu, kept her entire fortune in the scatulca mentioned earlier. Long journeys to Nicopolis and Constantinople had opened her eyes to the Ottoman world, and she began spending money on small objects that delighted her soul: not always jewelry, but musical boxes, glass parrots, painted clocks, or fans made of exotic feathers. Many of these were stored in the secret casket, along with her money and a garnet hairpin.

She could have described the scatulca even in her sleep. It had secret compartments, tiny drawers, a double bottom, and a button set into the lid which, when pressed skillfully three times in succession, revealed a hidden lock. In the lid itself, like a pencil case, were velvet pouches containing substantial sums of money and property deeds from Nicopolis.

In November 1792, a month much like this one, Elisabeta found herself without money and asked the doctor for her wages. He had no small change at the time. A heated discussion followed. She threatened to quit, and the doctor, to prove his good faith, wrote her a kind of guarantee note, promising that within a few days he would pay her the sum owed — thirty talers.

Autumn had set in; the frost had fallen. Bucharest was as melancholy as it is today. The carriage entered the gate, and the trunks were carried into the house. Elisabeta sat down on the stairs, while the four children who were then in Bucharest came out to greet their father. The doctor’s daughter wore short wooden pattens to keep her shoes clean, and the sound they made on the stone steps awakened memories in Fârțogu.

He removed his hat — a sable ișlic — and unfastened his fur-collared coat. And on that November day, as the sun struggled to break through the dim light, the doctor fell to his knees. Elisabeta on the stairs, his daughter’s wooden shoes, and then the alley in front of the house — these were the last things he ever saw.

Fârțogu’s death caused a stir, and for his family it was a catastrophe: Giorgiache Sculida had left no will. As a result, a quarter of his estate went to the poor box, and the rest was placed under the care of a guardian until the youngest child came of age, which would happen in a year’s time. Zoe and one of her brothers remained in the Bucharest house, under guardianship.

The older boys, seized by their longing for travel and convinced it was their duty to take over their father’s responsibilities, requested money. The administrator gave them 160 talers, as the law required.

With this sum, they left for Constanța and from there, by sea, toward Constantinople, to join their brother. They were unlucky: their ship was wrecked and they drowned — or so the rumor spread. In my view, two young men with some money, unprotected and impulsive, likely ended up in a slave market or sold to the galleys.

Of all those who had depended entirely on the doctor, the most wretched was Elisabeta. She had no access to the casket containing her belongings and could not recover her modest savings. The trunks, the scatulca, all the goods legally belonging to the doctor were passed from hand to hand and carefully entered into the inventory.

All that remained to poor Elisabeta, after long years of service, were the thirty talers for which she held a receipt. But to claim them she had to wait a year, until Zoe came of age and the inheritance was divided among the siblings. Only then could she ask for her money — a sum too small to found a life upon.

Poor, ill, and burdened by the guilt that Fârțogu had died upset, perhaps because of her, Elisabeta chose the path of the convent.

The entire story is recorded in the lengthy probate proceedings from the summer of 1794. Part of it is written by Elisabeta herself, in her petition addressed directly to the ruler, in which she claims the thirty talers owed to her. Naturally, throughout the document she refers to the doctor as Fârțogu, which makes me think that this was the name by which everyone knew him.

On the list of sums paid to creditors and heirs appears a final note: thirty talers were returned to a nun who held a receipt.

Scatulca – a small hand-held casket for valuables, often with secret compartments.

Arnauts – armed guards of Balkan origin, commonly employed as escorts in the Ottoman period.

Talers – large silver coins widely used in Central and Eastern Europe.

Poor box – a legally mandated charitable fund receiving part of an estate when no will existed.

İșlic – a high fur hat worn by elite men in the eighteenth century.