Saint Andrew’s Day, 1793. The city is preparing for the winter holidays, with baked pumpkin and unspeakable spells, for on the night of November 30 the gates to the subtle world open wide—especially around the Old Princely Court, where, among other things, stood the Princely Cellar, a vast storehouse filled with delicacies and barrels of wine, liqueurs, and preserves stacked on shelves. Over all this reigned Andrei, cellar master, salaried administrator, and holder of the rank of stolnic.

A few days earlier, a cook from Silistra had arrived in Bucharest, hoping to secure a position in the Palace kitchens. He had traveled for many days, accompanied by a girl—a thirteen-year-old child named Floarea. She had insisted on making the journey with him, hoping to find her mother in Bucharest.

Floarea’s story is not very different from that of Flori, a character in my novel Occult Beds. She, too, had more or less been left without a mother—one who had set off on a journey to Ismail, promising that one day she would make her way to Bucharest. In Floarea’s memories, her mother was still beautiful and charming, wrapped in shawls, owning a small case of jewelry and cosmetics inherited from her own mother, a native Bucharest woman, who had also given her a silver-framed mirror. Although life in Bucharest had once been pleasant, this affected woman, daughter of market sellers, had run away into the world, marrying a cart driver, a slave belonging to a merchant from Silistra. Not long after, Floarea was born—her name itself proof that she had been awaited and desired.

But life changes. The cart driver died, and Floarea was left alone, for her mother, in love with a certain Peea Rențiper (a fine name), fled to Ismail, leaving Floarea in the care of a neighboring cook so she could learn a trade. It was a good idea, really. In a year or two she might have become a skilled maker of rolls.

That cook, however—moved by who knows what impulses—slung his cooking kit over his shoulder and set off for Bucharest, determined to make his fortune. Floarea followed him like a dog.

So, on the eve of Saint Andrew’s Day, the keeper of the princely cellars went out for a stroll. It was a warm November, much like today, and townspeople were dyeing walnuts for the holidays. Musicians filled the air with their latest spicy tales, while on Lipscani Street Persian shawls fluttered beside silk anteri coats, cashmere garments, and embroidered muslins.

Andrei the stolnic regarded all this with indifference, preening himself in a fur collar and a Maltese turban adorned with yellow flowers against a smoky bluish background. Evening was approaching, and he was preparing for revelry, for on Saint Andrew’s Day Bucharest folk feast until dawn to drive away demons and ghosts, while women practice spells and divine the future.

When the carriage stopped—as often happens in traffic—the cook’s face appeared at the window, begging for a job. The stolnic was flattered, listening to him speak in Aromanian, mangling words, but above all impressed by his natural good sense: the man knew how to beg properly. He followed the carriage home, where the courtyard was already full of guests, grills, and musicians.

Understanding the situation, the cook offered a gift so as not to be forgotten—namely Floarea, who had run after her master from the Old Court all the way to Gorgan, where Andrei the stolnic lived. She was flushed and dazzled by everything she saw, especially the crowded courtyard. But at thirteen she had already seen enough of life; quickly assessing the situation, she realized that the stolnic’s household was better than the oven.

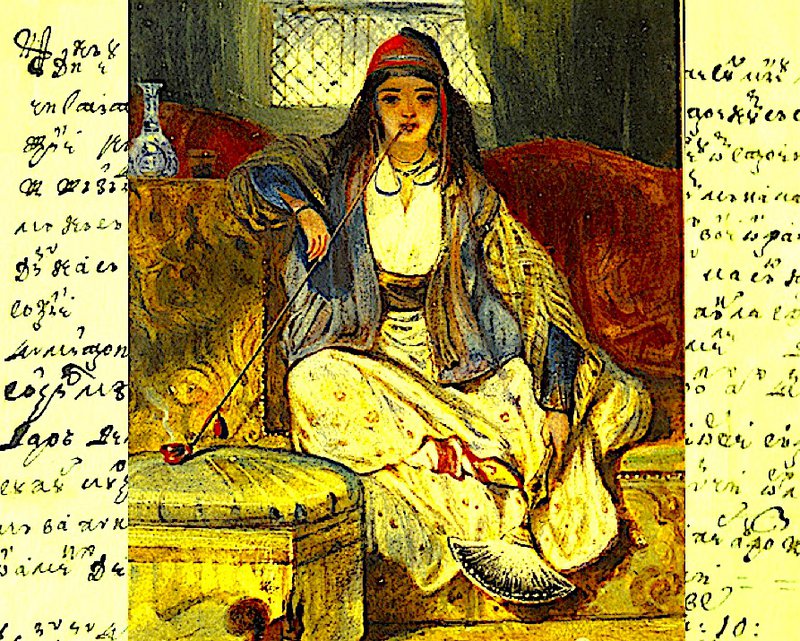

We do not know whether the cook was hired, but we do know that Andrei accepted the “gift.” Two weeks later he submitted a petition to the Divan, requesting an act of emancipation for the girl, on the grounds that her mother—traveling to Ismail with her new lover, Rențiper—had been born in Bucharest, as a free citizen. Floarea had no papers, it is true; that was precisely why her situation required resolution. And to dispel any doubt, Andrei wrote directly to the prince, explaining that although the girl bore the appearance of a slave—especially because she occasionally smoked a pipe—she was at least half free, given her mother’s origins.

Reading this description, I was reminded of a painting by Alexandre Gabriel Decamps, which I include here: a girl from Cyprus, devoted to the art of tobacco.

Alexandru Moruzi, who read every such case—remember—was impressed by the story and reached a decision fairly quickly. On Christmas Eve, he decreed that Floarea should be declared a free person—but not immediately. Only after she married. Until then, she was to remain in the stolnic’s care, a slave in all but name.

And perhaps Floarea would have died a slave, and none of this would have happened, had she not entered the stolnic’shouse on Saint Andrew’s night—the patron saint of all spirits.