One can speak at length about protective objects: a bead kept in one’s pocket, a blessed little cross, a lucky jacket, and so on. In older times, Europeans carried other beneficial artifacts as well. Lawyers made sure to obtain a chameleon’s tongue, frightened women wore necklaces made of owl bones, and healers inhaled powdered herbs to enhance their powers.

Among the many apotropaic plants was lovage, kept at the bottom of a pocket or sewn into pillows and mattresses. It was added to livestock feed and thrown into wells. Lovage was used to treat the mad—those seized by the căluș—and it was also used to cleanse silver water pails, which once held drinking water.

The great respect earned by lovage comes from ancient times. As proof, I will invoke a nineteenth-century folktale—one I also mentioned in my recent novel Homeric. Widespread across Romanian territory, the story was collected in the Arad region and published by Simion Florea Marian in Popular Botany.

A man and a woman loved each other madly. Young, beautiful, warriors. His name was Lovage, and he wielded a sword. The woman was a blonde beauty, clad in chain mail. Her name was Celandine.

In those days, the land was full of insolent brutes, and Lovage and his beloved cut off arrogant heads without mercy. Of course, these brutes were not human beings but demonic creatures—perfidious specters, revenants risen from their graves, werewolves intoxicated by moonlight, and above all a series of mediocre little devils who believed themselves the center of the world. In this sense, I must confess that of all the evils in the world, parsley’s vanities make my hair stand on end. In a way, the times of the valiant Lovage were not so different from our own. Nearly all the devilry of the planet wanted to rule over firewood.

Thus, Lovage and his blonde beloved slaughtered without pause any monstrosity that flaunted its tail with airs—from louts with bulbous noses and painted horns to imitators hiding behind the most pious and venerable faces. About the latter I must add a word: among the many perverts of all ages there exist certain well-mannered epigones, tight-lipped to display how much suffering they harbor within, people with faint voices who theatrically string together other people’s words and phrases, who dress in the clothes once worn by their teachers or eat the dishes they have heard were served at royal tables. These pouty clones were also the easiest to kill.

Night after night, Lovage and his beloved left behind waves of blood, especially along the forest edges—among which Cotroceni was the most dangerous, at least here, in the capital of Wallachia, a favored haunt of nocturnal creatures. From fallen fairies to former heroes and aspiring good-for-nothings, from illiterate sycophants to the most pretentious mediocrity—all the refuse of the obscure world had conquered Bucharest.

Embracing, the two warrior lovers returned at dawn to their homes, with the satisfaction youth alone can give. They earned a reputation as defenders of the city, and townsfolk began to invoke their names whenever dusk caught them in the streets. Helpers appeared as well, among them the fierce Odolean and a fragile adolescent named Avrămeasa—hence the ghosts’ song sometimes heard at midnight near Dura’s Lake:

If only there were no Lovage

And Odolean the dog

And Avrămeasa the whore

The whole world would be ours.

But all stories have a shadowed side. One night, Lovage was caught in the middle of a hysterical crowd of specters and, despite his valor—insufficiently praised until now—despite all his warrior’s qualities, he was gravely wounded. And when a warrior takes a lance in the back, all the brutes leap upon him. Though he might have escaped with his life, his beloved chose to die fighting beside him.

The two, as the saying goes, sold their lives dearly. They were cut down by the swords of an army of demons after killing half of them. Their blood, heated by desire, mingled forever with the blood of their enemies.

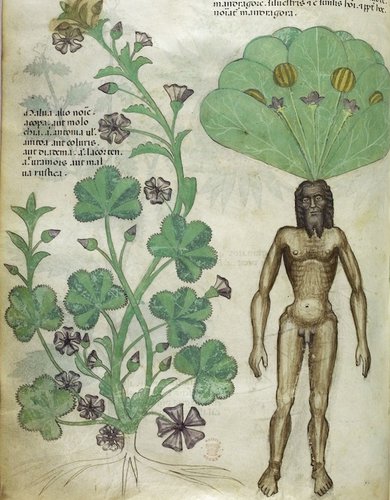

When the sun shone again over the Dâmbovița, on the spot where the two now-legendary heroes had fallen, two plants sprang up: lovage and a yellow flower some call celandine, others the hero’s cross. Their fragrance still preserves something of youthful breath, yet because their blood mingled with that of demons, the leaves of these plants also retain the scent of the other world.

That is why it is wise to carry with you a leaf of lovage or a flower of celandine—plants which demons, in their stupidity, believe to be of the same blood as themselves.

Therefore, at times, fraternizing with the devil is far subtler than that vulgar road across the bridge.