On the night of the Resurrection, miracles always occur—some so striking that four or five generations never forget them. Others are recorded by a single hand and periodically rediscovered by eyes that have nothing better to do. I belong to this latter category. Leafing through a book a few days ago, I came across a note, a short text written two hundred years ago. At first, I thought its author must have belonged to a family of clerks, perhaps a pretentious copyist from some Phanariot household. But since no marginal note ever remains suspended in questions, I can tell you what I discovered next.

Everything began in April, a month that always arrives with whims and flowers—usually undecided, full of perfidy, sometimes even bringing rain and snow, but above all swept by a harsh wind that cuts into flesh. Under its pressure, the plum blossoms scatter, and among all these April phenomena there also appear some beings forgotten by the world, known as mărmănjici.

Some say they were once helpers of the goddess Demeter, though this may be nothing more than myth.

You do not see them; they are tiny. But their eyes are like lasers—they pierce straight into your brain. Once they have looked at you, you dream of them at night and have no idea where you know them from, without realizing that they have sliced directly into your cortex to leave their faces there forever.

It is known that they appear in April, becoming especially bold around Joimari, when one can speak of an invasion. Although their greatest power comes at night, when they enter your dreams, there are people who see them during the day as well—and afterward can never forget them. An encounter with the mărmănjici makes you understand certain mysteries.

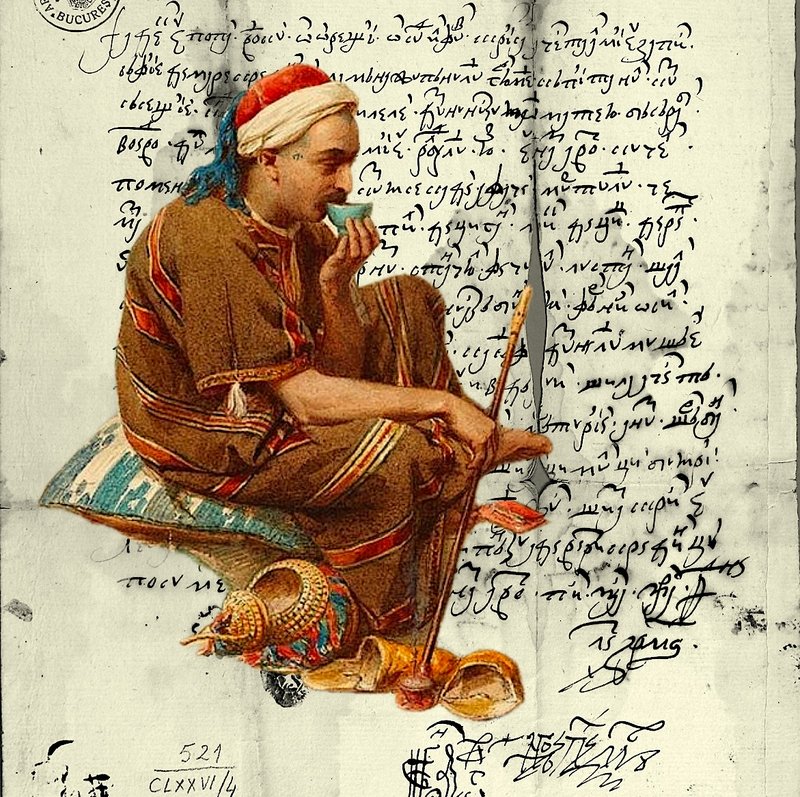

In Phanariot Bucharest there lived a refined fellow who practiced a profession rarely pursued by a man: embroidery. And not just any embroidery, but the princely banner, unfurled during the great holidays. It was carried through the streets in spring and depicted, alongside the eagle, the Holy Emperors Constantine and Helena, protectors of the city of Bucharest.

This was no slapdash task, but meticulous labor, done with a fine needle and silk thread.

The elegant man was a master embroiderer, familiar with many techniques. He made collars and ruffles, scarves with floral motifs and twisted letters, but above all he embroidered slipper uppers and small handkerchiefs meant to be waved beneath the nose at important meetings.

That April—around Palm Sunday—his work was nearly finished. The banner, made of yellowish silk and edged with gilded thread, bore on one side the coat of arms with the eagle, and on the other two imperial figures, carefully worked in pale thread, without stridency or unnecessary ornament. They were emperors, but stylized, embroidered angelically, like beings dropped into the waters of the fabric to float forever.

The Bucharest embroiderer was happy. The banner was no ordinary piece, but a masterpiece worthy of being kept in princely chests.

That evening he was to deliver it to the back gate of the palace, where a tall servant would pay him. But money was not what mattered. In the days to come, when Ipsilanti would leave the house, the entire city would have its eyes on the banner. Not only during Lent, but also afterward, during Easter, on Saint George’s Day, and especially once the promenades and garden festivities began.

His banner—thin and delicate—would flutter at the head of the procession. The banner always came first. After it came the lăutari, and then the rest of the cortege: the prince’s carriages and the army dressed in gaudy uniforms.

But the most anticipated celebration of all arrived on Saints Constantine and Helena’s Day, when the entire city took to the streets. The banner passed along the main thoroughfares, up to the Metropolitan Church and back again. And there was no Bucharest resident who did not ask who had sewn the banner, so that by evening the author’s name was known throughout the city.

Not to mention May 22, when the princely stud was brought out. All the merchants gathered early in Colentina. In light tents and a pleasure pavilion, the ruler and his entourage took their places according to rank. Between the tents stood the lăutari, ready to play. Then the parade began before the prince, with the entire population gathered on either side of the road toward Băneasa. First came the banner, slowly, carried by a rider without haste. The crowd fell silent in amazement; the banner fluttered like a gust of wind. Far behind it came the horses—one hundred of them—released onto the ceair, that is, allowed for the first time that year to graze freely on a special pasture stretching all the way to Băneasa Forest. For forty days, the length of the horses’ freedom, the banner fluttered on the fence of the pasture, raised on a pole, beaten by the wind and visible from afar, as a sign that the horses’ celebration had begun.

Naturally, during this time people celebrated in the gardens—not for a day or two, but for all forty days the ceair lasted in the town.

Throughout this period, the refined embroiderer moved from one garden to another, puffed up with pride, listening to everyone’s compliments. There was no one who did not praise the banner. Naturally—it was the event of the year.

On the eve of all this, the refined man now stood ready, having even made himself a new shirt that highlighted his caramel-colored complexion and pitch-black eyes.

He took the banner, wrapped in a thin cloth, and set off for the palace, never suspecting that the mărmănjici had passed through there. The rest is predictable and recorded on the page: the banner, embroidered with such care, had turned red—red enough to enrage a turkey.

The embroiderer was devastated. That spring he did not leave his house again. All the major holidays passed with older banners, and the town believed the refined man had lost his talent and could be forgotten.

But he was not the sort of man to leave the game so easily. For many days he investigated. He asked around to find out whether anything similar had ever happened. Some told stories of old times when many things had been found strangely colored—even eggs in the henhouse, which eventually gave rise to an Easter fashion. Others spoke of painted fingernails or blue goats. In short, there was precedent.

The embroiderer suffered in silence for a year. The following April he was ready, determined to guard the entrances. He set traps, slept little, and kept his mind fixed on the guilty beings, bent on coloring the world.

One Joimari morning, he passed through the lettuce beds. He was thin, sleepless, with sunken eyes. And as he peered among the small leaves, he encountered lights that churned through flesh and entrails. And then, at last, he saw them: among the lettuce bushes, beings no larger than a fingernail were watching him with taut attention. There were hundreds, thousands perhaps—mărmănjici it had been his fate to see. And gazing steadily at them in that hostile morning, breathing in the chill of April air, the refined man understood, without needing a single word, that the mărmănjici had been well intentioned. They had nothing to do with the banner. They were not punishing him for guilty ancestors. They had only wanted to help.

And seized by an unexpected happiness, such as comes before Easter, the embroiderer laid down his needle and wove a carpet—so that his descendants might also know what a mărmănjică looks like. Whoever wishes to see one can surely find it today at the National Museum of the Romanian Peasant, in the collection of ancient woven rugs and kilims.