Filimon the tailor was born with a cricket in his ear, a tiny, extremely loquacious creature. It spoke incessantly, yet never became tiresome, its topics always timely and useful. Though it loafed about on his eardrum, it was fully plugged into the facts of the world: it saw through Filimon’s eyes, heard what he heard, felt caresses, the touch of rain, and had well-formed opinions on many things—especially perfumes and flowers.

Filimon respected it deeply and followed the cricket’s advice, which is why he prospered. In general, he got what he wanted out of life. Whenever he encountered some irascible fellow, he listened attentively, so much so that, watching him, you’d think he fully agreed. In truth, he was listening to the cricket’s commentary, brilliant in many fields. At the right moment, once the hothead had cooled a little, Filimon’s warm voice would sound, repeating word for word what the cricket had said. The irascible man would be left gaping, while everyone else—the audience, fed up with his grievances—would immediately side with Filimon, who in time became a sage, a man people listened to, then an authority, and finally an exponent of the crème, the elite, of those few clever operators who know exactly when to speak, whom to bet on, and whom to flatter.

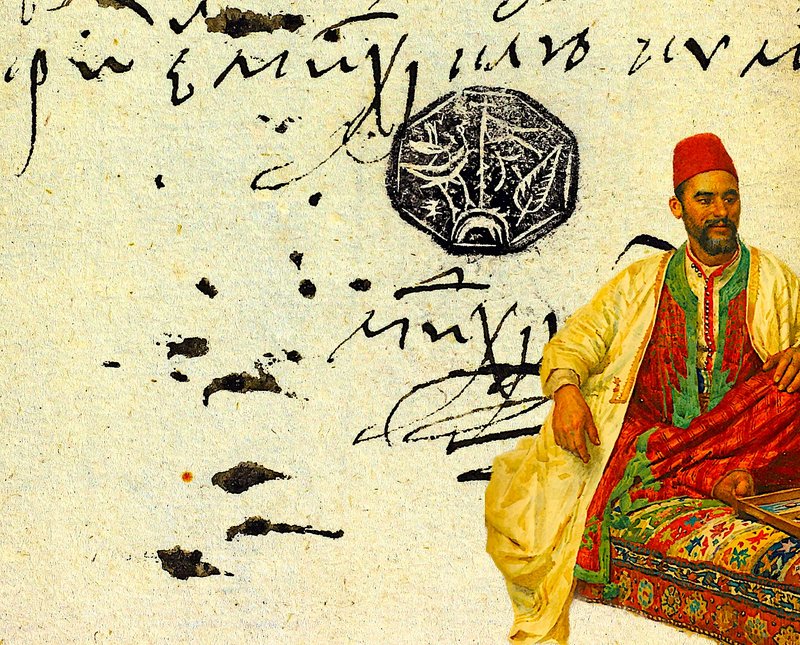

Filimon made clothes, chiefly one particular garment prosaically called a polonaise: a velvet jacket with a high collar and many braids, short, with embroidered sleeves, made according to the Bucharest fashion of the time—large flowers on cuffs artfully slit up to the elbow. Worn by both men and women alike, the polonaise was in great demand and was not only Filimon’s masterpiece but had become his hobby. He would cut a polonaise, sell it at a good price, then let himself be led for several weeks by the cricket through the Bucharest of pleasures.

His cricket knew how to choose women, warning him whenever the chances of seduction were slim. It would tell him, Look, Filimon, this woman is ready to love you—or on the contrary, stay away, old man, don’t go near that one, you’ll surely run into trouble. The cricket was always right; it seemed an expert in affairs of the heart. And the tailor, night after night, undid lace and velvet, revelled in Malta sheets. He knew which women had been left alone at home, was familiar with the doors he could knock on. He slipped at midday into chambers guarded by mercenaries and had managed to enter monasteries and palaces ringed with walls. Whenever he saw a woman at a carriage window, he discreetly stroked his ear, and the cricket would brief him on her entire life and habits.

Shopkeepers embraced in the corners of their shops, girls walking their dogs, sophisticated young ladies who waited night after night on window ledges, adolescents eager to learn life’s mysteries, wives kept under lock and key, slender girls hunched under countless complexes, arrogant women who had sworn never to lower their standards in men—whom they believed they chose themselves—and finally more mature women, some who had lost their judgment or were desperate: all the women who had entered Filimon’s retina eventually came to love him, to sigh for him, or to tear their hair out.

The moment he opened his front door, he was besieged by women who wanted to be loved, who believed in a lifelong bond. These creatures multiplied alarmingly, until the tailor’s former peace became merely a memory, itself on the verge of being erased altogether.

One day, the cricket told him there was no point in going out in Bucharest anymore. The city was finished for him. Even the cricket’s powers no longer worked. Filimon had overdone it; it was time to move to another city.

The tailor was depressed and worked absent-mindedly on a polonaise for a man from Vâlcea, who was to pick it up the next day. Shut inside his house, he thought about all his adventures, and as he mentally listed all the women he had conquered, he realized the cricket was right.

Still, leaving Bucharest was unbearable.

What could happen if he stayed just a few more days?

The cricket was evasive in its answers, but something serious was bound to happen.

He finished the garment, stuck the needle into the silk cushion, and stepped out onto the veranda. The city was asleep, and in his ear there was a black silence. From the direction of the Metropolitan Hill came a rustle, as though a torrential rain were approaching, and somewhere above the Dâmbovița the lights of day were already glimmering. Or so he thought, when from all sides the invisible tongues of excess seized him.

Kneaded into dough, a lump of ambitions, worked and stretched in all directions, the tailor was finally lifted up and carried over the city, so that fragments of what he once had been fell into several intersections. At Romană Square, in Lipscani, near Boteanu, and on Metropolitan Hill, one can still see today some glassy pebbles left from the tailor’s avid being, and perhaps from the abused soul of a cricket from the other world.

Many seek these pebbles, believing them to be talismans of success.

Around noon, the man from Vâlcea came to fetch his coat. The house was deserted, but the polonaise shone, impeccably tailored and set on a mannequin. He left the money and took the coat, and back home, after a few wasted hours on the road, he found a cricket in his pocket.

What followed is not worthy of my pen. Suffice it to say, it did not end well. About a year later, a hand upon which some eyes had wept wrote on a book the ending of this story: “April 15, 1750, when uncle—may the earth lie lightly on him—bought Scaraoțchi’s polonaise.”

This note, considered cryptic by many, also encloses the biography of Filimon the tailor. If uncle, anonymous as he was, is remembered by his family, Filimon’s story, like so many others, remained underground in memory.

P.S. I forgot to tell you: if you find a little pebble in the places mentioned, keep it for a few days—long enough to make a good impression—then throw it into the fire.