In Modern Greek, zernekades meant the narcissus flower, which the Turks transformed into zerenkadá, and which reached Romanian as zarnacadea. During the Phanariot era, blue shawls embroidered with zarnacadele were worn; bed sheets had zarnacadele sewn into their corners; silk anteris featured them along the hems. Hairpins, buttons, and brooches shaped like this flower were fashionable as well. Until then, it had been called ghiocel-de-baltă (marsh snowdrop), and it would later become known as the narcissus, sometime in the nineteenth century.

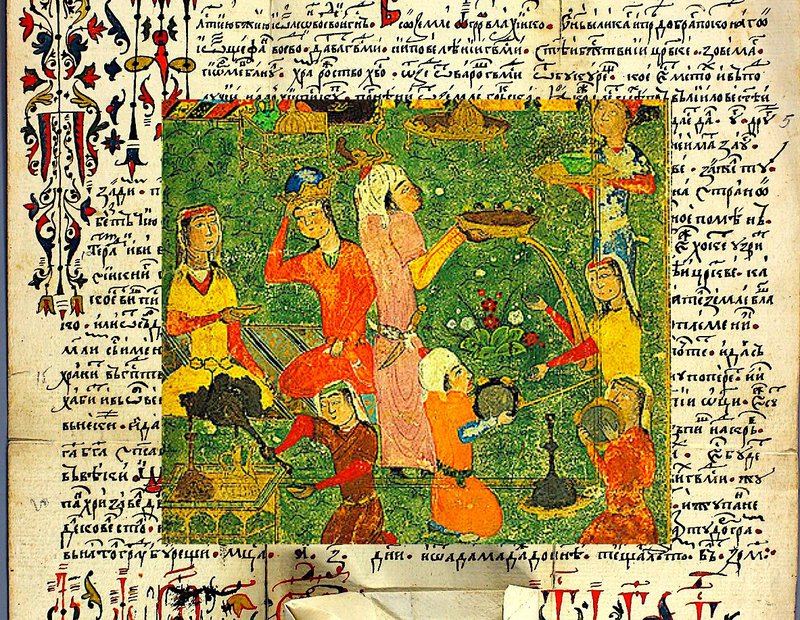

Sometime in the early 1700s, there lived in Bucharest a cook, a great lover of sweets. He knew how to make many desserts, and among his inventions was a small cake he called zarnacadea. Today we might call it a mini loaf cake, baked in an oven—a rarity at the time, since Romanian sweets, as their name suggests, were usually fried in pans, most of them belonging to the category of doughnuts and turte (griddle-baked tarts). This cake, baked in the oven, was different. Lightly soaked in syrup, it had a thin layer of ground walnuts, another layer of yogurt thickened with pistachios, and on top a white flower made of meringue, discreetly decorated with rose and lemon jam. The cook made the cake almost daily. And I forgot to tell you: he was the cook at the Yellow Duck inn, near Colțea.

His zarnacadea became so popular that it was sold separately, through the inn’s window. Like any dessert, it was addictive. But more than that, a rumor spread that it brought increasingly strange dreams. One woman dreamed she would receive an unexpected inheritance, and shortly afterward she received a message announcing that an uncle from Vidin had died without heirs, leaving her his entire fortune. The story spread from one person to another, and the cook, listening from the window, remarked—of course I know the woman; she often buys my zarnacadele!

Then there was a young girl who dreamed she would marry the son of a shopkeeper who had never considered marriage. Until then. After the girl told her dream around the neighborhood, the young man began to think differently, and after a few visits to the gate of the bright-eyed dreamer, he decided to ask for her hand. The wedding was still some way off, but the facts proved that zarnacadea was magical. Buyers multiplied, and the Yellow Duck was besieged. Long lines formed at the inn’s window, with people coming even from the provinces. And with that, the dreams multiplied as well.

An arnăut dreamed of a bag of money, which he inexplicably found the next day in his garden. Pitaru Băjescu, a sensible man, after eating the cake, had a dream in which his wife was unfaithful. He joked about it publicly until a rather insolent servant supplied details that confirmed the dream.

Amid the scandal in the Băjescu household, demand for zarnacadea grew so much that the innkeeper hired a new cook. Business flourished, the flowered cake became queen, and the Yellow Duck the most sought-after establishment in town.

But as it happens, others soon began making zarnacadele as well—some improved with a layer of sherbet, others with flowers of different colors. Cakes appeared with indrușaim, with apple blossom, even with dandelion. As they multiplied, people lost interest. Within a month, the inventor-cook returned to the griddle, limiting himself to stews and polenta.

Still, the glorious episode of the zarnacadea remained in history, so that sixty years later, when it had begun to be called “narcissus,” some people were still sleeping with the flower under their pillow, hoping to dream their future.