Whenever I get the chance, I tell my friends to read translated books. As an American, the idea of only reading stories from traditionally “Western” perspectives sounds a bit boring – the world is bigger than our own personal experiences, and is more varied and beautiful than what we define as our “comfort zone.” With this in mind, I was very excited to hear that Doina Ruști’s historical fantasy, based in Bucharest, would be receiving an English translation.

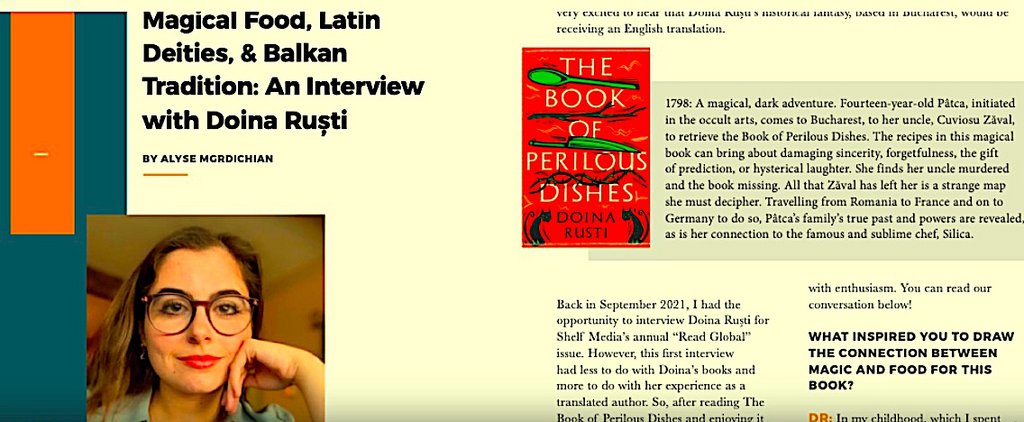

“1798: A magical, dark adventure. Fourteen-year-old Pâtca, initiated in the occult arts, comes to Bucharest, to her uncle, Cuviosu Zăval, to retrieve the Book of Perilous Dishes. The recipes in this magical book can bring about damaging sincerity, forgetfulness, the gift of prediction, or hysterical laughter. She finds her uncle murdered and the book missing. All that Zăval has left her is a strange map she must decipher. Travelling from Romania to France and on to Germany to do so, Pâtca’s family’s true past and powers are revealed, as is her connection to the famous and sublime chef, Silica.”

“In my childhood, which I spent in a small village (Comoșteni) in the Danube Valley, all food had magical properties. For example, we would imprint a star with many rays onto our bread, as a representation of the sun, made by using the bolls of a plant called “velvetleaf” (attached below). It was inconceivable for us to eat bread without this symbol. Often, we would also add a few drops of holy water in our food. Many of the enchanted dishes mentioned in the book were prepared in our home – we had both an elixir and a dish for any type of disease. There is magical culinary art preserved in the folklore books of Europe, therefore here in my country as well. In one such book I read a 17th century recipe for a Trigonella leaf salad. These leaves need to be added in small quantities, and I remember how we’d prepare that salad in our house to sleep well during the night. Then I found out that these leaves are used in medicine for preparing sleeping pills, but also poisons – hence, caution is advised. Domestic mythology is part of my legacy, and I rediscovered it academically, which revealed to me the complexity of archaic life.”

“Actually, my approach was rather based on maieutics, moving from question to question. I started by reading a document from the 18th century – it was a complaint made by a noblewoman against the prince. He had kidnapped her cook. Obviously, I wasn't interested in the outcome of the actual conflict, but I started wondering what culinary skills that cook could have had to justify his kidnapping. That’s why I then read a recipe book from the royal court, dating back to 1690. Many dishes were bizarre, and they reminded me of the alchemy of magical elixirs.”

“My fictional world is rooted in my childhood. Everything was possible in Comoșteni. First of all, our house offered various possibilities for expanding the fantasy realm: it was a large house, with many rooms, and each of them hid chests, nooks, trap doors leading to the cellar, attic, or ice chamber, numerous objects passed down for several generations, and in the yard there were many other buildings, carriages from the old days, toys of previous generations, stables, the fig plantation, a cherry orchard, and a summer kiosk covered in vines. On top of that, the village is located near a river (Jiu) and the island of Copanița, where we’d often hunt coots; the forest was not far. Neither were the ponds, and there was even a stone quarry … all these elements have laid the foundation for my fictional worlds, and every time I write a book, they naturally shape my artistic sphere. I couldn’t have written about Pâtca without my memories from childhood, when I was actually called by that name (a strange word from Bulgaria, meaning "something small"). Only afterwards, having lived in this region, I absorbed the elements of the 18th century, out of a Bucharest which hoped (as did all of Europe) that the great empires would crumble, first and foremost the Ottoman one. My imagination is built on solid ground, which is why I always start with a map, just as I did now (I’ll attach it here). It illustrates the geography of Bucharest at that time, but also the houses mentioned in the novel, the main characters, and the streets which have endured through time.”

“I am a Latinist, and that is why I used elements from peripheral Latin mythology in my book. Sator was a generic name for the supreme creator of the world, and was only rarely used in the Latin world. In school, I studied a well-known magical square in Latin, on which is inscribed: Sator Arepo Tenet Opera Rotas. Sator was simply a synonym for the supreme god and, historically, there were no Satorines … however, the entire 18th century was full of secret societies and confraternities, like the Rosicrucians, so it did not seem impossible. To prepare, I read a lot about the esoteric societies of the 18th century. The Enlightenment ignited, among other things, atheist movements and a rejection of the Church. As a result, there were groups that advocated a new religion and produced rich literature – these esoteric societies were a result.”

“She is not a figure from folklore, but she synthesizes several Romanian and universal beliefs about cats. They say that the real name of the cat can never be uttered. There are also many superstitions and myths about the taboo of revealing sacred names. Indeed, it’s comfortable to hide your real name! Moreover, there are symbolic connections between the cat and Friday, seeing as the name of this day, in Romanian (as in all neo-Latin languages), comes from Venera-Venus, the goddess of love and seduction. Last but not least, many dark spells require a black cat. However, Cat-o-Friday herself is a white cat, making her a beneficent witch.”

“Thank you, dear Alyse! Of course, the process was complicated, and we’ve made several attempts. This time, I was lucky to find an agent who managed to secure a publisher, but it was surely a new path for me. Unfortunately, I’m not confident enough in my English to establish how far James Brown's version strayed from my novel. However, I do know that any translation is practically a new composition, in the same way a screen adaptation of a book is a new composition.”

În română

Întâmplător am dat peste un scurt manuscris, din 1798, în care o femeie se plângea că i-a fost răpit sclavul, deoarece era cel mai bun bucătar din oraș. Bineînțeles, am vrut să știu ce gătea, ce gust aveau mâncărurile respective și-am căutat rețetare. E incredibil câte rețete culinare s-au păstrat în Arhivele Naționale! De aici s-au născut alte întrebări, legate de ingrediente, costuri, context istoric etc., iar când povestea bucătarului s-a conturat bine, am scris-o fără să mă întrerup.

Pe măsură ce-l descopeream pe bucătar, îmi aminteam de bucătăria copilăriei, de vremea în care eu însămi eram Pâtca și mi s-a părut normal ca naratoarea să aibă vârsta la care bucătăria e un loc magic și misterios. Cam la aceeași vârstă și eu am fost nevoită să-mi iau viața în propriile mâini.

Romanul meu merge mai curând spre aventură, e povestea unei adolescente care rămâne singură pe lume, e pe punctul de a-și pierde libertatea, încrederea în oameni și chiar și în vrăjile familiei. O vor salva generozitatea unei femei și câteva lucruri învățate în familie. Or, familia ei face parte din cultul satorinilor, ceea ce m-a dus spre numeroasele cărți mistice ale secolului al 18-lea, de la imagologia criptica lansată de rosacrucieni, la mistica lui Maistre, la meta-realitatea lui Swedeborg dar mai ales la fantasticul iluminist din Manuscrisul găsit la Saragosa al lui Jan Potocki sau la Frankenstein-ul lui Mary Shelley. În mod indirect, toate aceste cărți se află undeva în fundamentul romanului. Dar desigur, peste ele au venit zoologiile medievale, cu nemaipomenitele rețete (farmaceutice sau culinare), culegerile de folclor și mitologia latină, cu periferiile ei populate de zei mărunți și de miracole care au făcut posibilă reinventarea lumii în epoca medievală.

Iar, a propos de acest imens material, m-au amuzat în primul rând legăturile simbolice pe cât de bizare pe atât de rezistente în timp. De pildă Avicenna recomanda în tratatul său de medicină ca avocații să poarte în timpul procesului o limbă de cameleon. Aceasta le va spori talentul, îi va duce spre victorie. Or, nu poți să treci peste o astfel de prescripție, fără să ai în minte tot parcursul ei epic, de la prinderea șopârlei, la sacrificarea și apoi la operația barbară de a-i smulge limba, de a o săra și de a o usca la soare, pentru ca după ceea să fie transformată în talisman, pe care un avocat o va purta la gât cu încredere. Nu rețeta în sine interesează aici, ci sfatul ascuns în ea, legat de mobilitate și retorică. Pe modelul aceasta de rețetar am mers în romanul The Book of Perilous Dishes.

Istoria nu e făcută doar din informații, o ficțiune poate să individualizeze părți intrate șablonard în conștiința generală, să nască întrebări, să ajute la demontarea unor mituri. Am trăit în comunism și am constatat că istoricii n-au consemnat adevărata substanță a acelui regim, anume rezistența pe care ne-am dezvoltat-o la informație. Îmi aduc aminte că în zilele exploziei de la Cernobâl, evenimentul s-a anunțat la radio și-am fost rugați să stăm în case. Bineînțeles nici eu, nici prietenii mei n-am crezut că e adevărat. Când ești obligat să iei parte la o minciună oficială și epidemic răspândită, încep să-ți apară funcții și însușiri specifice, te transformi în altă specie. Despre asta am scris în romanul meu principal, Fantoma din moară, și-mi place să cred că această carte de ficțiune a readus în discuție acest aspect: comunismul ne-a dat nu doar scepticismul, dar ne-a obligat să ne creăm o realitate alternativă, despre care astăzi nu aflăm decât din cărțile de ficțiune.

Mi-ar plăcea să am elixirul gemenelor, o poțiune care ajută, printre altele la descompunerea timpului, la teleportare. Mi-ar fi plăcut să traversez în viteză câteva dintre episoadele vieții mele.

Tot romanul este construit pe ideea că există o forță universală (Sator) care poate fi manipulată. Direcția istoriei este determinată de oameni vizionari. Uneori ei se numesc vrăjitori, alteori savanți - nu prea contează. Sunt acei inși în stare să miște masa majoritară, să-i contamineze pe cei mai mulți dintre semeni cu dorințele și scopul lor. Iar în cele mai multe cazuri motorul mișcării funcționează cu fantome venite din trecut. Așa se întâmplă și în romanul meu.

Sunt latinistă și de aceea am folosit în carte elemente din mitologia periferică latină, de exemplu Tutillina era o mică zeitate agrară, care patrona plantele, un fel de spirit minuscul al vegetației. Dar în romanul meu, ea este o vrăjitoare din ordinul satorinilor. Tot așa Rusor e o zeitate neinsemnată din patrimoniu latin, care făcea ca obiectele pierdute să fie recuperate. Sator era un nume generic pentru constructorul suprem al lumii. Nu era decât rareori folosit în lumea latină. Dar eu l-am preluat aici ca să creez o entitate integral imaginată de mine. Când eram în școală studiam la latină un careu magic, binecunoscut: Sator arepo tenet opera rotas. Putea fi citit si de la coadă, în toate direcțiile de fapt. Dar nu a existat propriu-zis o zeitate cu acest nume, ci era doar un sinonim pentru zeul suprem. Evident, n-a existat nici ordinul al satorinilor… dar tot secolul al 18-lea a fost plin de societăți secrete și de confrerii, ca rozacrucienii, de exemplu.

Am văzut că la doi ani după publicarea romanului meu s-a făcut un film cu numele Sator.

Nu am făcut o cercetare. Dar despre societățile ezoterice ale secolului al 18-lea am citit foarte mult. Spiritul iluminist, al secolului al 18-a a generat printre altele, mișcări atee și o dezicere de Biserică, de creștinismul oficial. Prin urmare au apărut grupuri care pledau în favoarea unei noi religii și care au produs o literatură bogată.

Nu este o figură folclorică, dar sintetizează mai multe credințe românești și universale despre pisică. Se spune că numele adevărat al pisicii nu poate fi rostit. Despre interdicția de a rosti numele sacre există de asemenea multe superstiții și mituri. Și într-adevăr, e confortabil să-ți ascunzi adevăratul nume! În plus, între pisică și ziua de Vineri există legături simbolice, căci numele acestei zile, în română (ca în toate limbile neolatine) vine de la Venera-Venus, zeița iubirii și a seducției. Iar nu în ultimul rând, multe dintre vrăjile tenebroase cer o pisică neagră. Bineînțeles, Cat-o-Friday, așa cum este reprezentată pe casa ei părintească, este de culoare albă. E o vrăjitoare benefică.

Oh, da, multe dintre mâncărurile vrăjite din carte se făceau și în casa noastră. Apoi, la intrarea în casă aveam un câine roșu, exact ca și Maxima Tutillina, despre care, în vremea copilăriei credeam că e paznicul casei. Deși era o statuetă de ipsos, mereu am avut impresia că este viu:)

Dar dincolo de practici și superstiții se află spiritul balkanic, la care eu sunt conectată. Pentru mine universul ficțiunii este zugrăvit în alb și roșu, e o lume solară, cu multă lumină și cu o predispoziție euforică, pe care mi-a dăruit-o copilăria mea, petrecută pe malul Dunării.