Marghiol is a word with a history — and with a certain personality. Coming from the Greek marghiolos, from where it spread into the Romance languages (mariole), it originally meant adventurer, frivolous fellow, later manipulator, seducer, even trickster. It entered Romanian before the Phanariot era; in any case, it is attested during the time of Brâncoveanu in all Wallachian chronicles. The marghioli were scatterbrained types you couldn’t rely on, whose word was worth nothing. Insurgents, traitors, layabouts — though certainly not devoid of charm. And among them, Staicu is the one most frequently illustrated with the epithet marghiol.

He is a sort of patriarch of the marghioli, especially since he also had ancestors of the same marghiol-like nature, who left him as inheritance the instincts of rebellion, adventure, and betrayal.

Staicu — also written Staico — a boyar from Merișani, went down in history as Brâncoveanu’s enemy, a failed conspirator. His family had produced insurgents since at least the early 17th century, one of them being a certain Bucșanu, who in 1611 planned a revolt against Prince Mihnea. The next generation also produced schemers, but Staico’s story is the most spectacular, recorded in several chronicles.

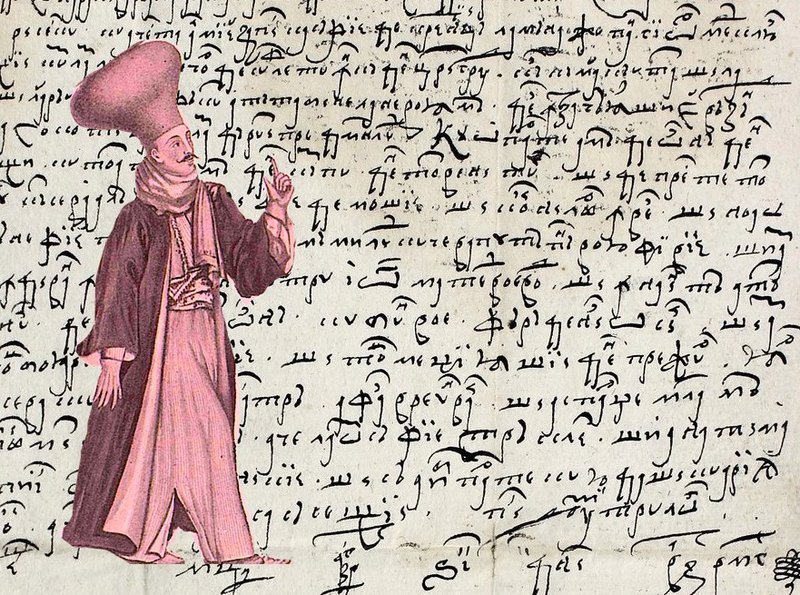

A supporter of the Germans, anti-Ottoman, Westernized, allied with other cosmopolitan types, an exiled boyar and creator of intrigues, this Staico dreamed of becoming prince. He was a dark-haired man, slim, with a very well-groomed beard, European-style haircut, and full of whims — an adventurer who lived mostly in Transylvania, a man with extensive correspondence.

Many pages have been devoted to him, especially today, where he is often portrayed as a born protester.

But first of all he was a marghiol, as the Brâncovenesc Anonymous calls him.

Staico was captured in Istanbul with a letter on him that spoke explicitly about dethroning Brâncoveanu. The irony is that the letter had been sent to him by one of the informers secretly paid from the princely treasury: “news came that they caught Staico the cupbearer and found the letter of Cupbearer Dumitrașco in his money pouch.”

One could say a special entrapment operation had been organized for him.

The marghiol Staico was tortured for several months, kept in prisons, until Brâncoveanu finally decided he was better dead than alive. He was hanged at Obor, on market day. The crowd got drunk that day, and after a few weeks of storytelling about him, he was forgotten.

Even after his disappearance, the word marghiol continued its career, softening along the way, until it even entered poetry: “filled with longing and marghiol.” Later it acquired a feminine form and became a beloved girl’s name. Hangerli’s daughter, for instance, was named Marghioala. A long line of charming Marghiolițe followed, whom the interwar writers mocked into extinction.

Today the word has vanished, leaving behind only a faint hint of vulgarity. Why? Perhaps because it never received enough support from intellectuals. Tell the truth — if I hadn’t told you all this, what would you have guessed marghiolmeant?

Published in Adevărul