In the National Archives lie countless documents, and I must say from the start that nothing in this world has the force of handwriting. In it reside the mind, ambition, and—last but not least—the true emotions of a person. When you see cramped, strained handwriting, you should not assume a small, timid, socially awkward individual. Graphology manuals can be wrong, you know.

In earlier times, when handwriting truly mattered, people wrote on their knees, on the corner of a table, in the palm of their hand, even on the walls of their houses. My true birth certificate was written on the door of a carriage, in my family’s storage shed, where—as I believe I have already mentioned—many historical objects were kept. I was, of course, born at home, attended by a doctor, a midwife, and a priest, in a room where no one had been born before or since, on a rainy day. My grandmother ran into the shed, knocking over boxes of hats, chandeliers, and washbasins, just to reach the carriages—odd antiques themselves—and wrote on the door of one of them: “My son has a child, I am old!”, noting the exact date of my birth.

Sometimes she wrote the day and month on eggs, so we wouldn’t accidentally eat the old ones, or on the goat’s horns, with chemical pencil, so we wouldn’t forget its age. This, after all, is the purpose of writing: to remember. My grandmother wrote on newspaper margins, in lined notebooks, on the wall of the summer kitchen, on the little table in the gazebo. It was a habit she had inherited, and it taught me why essential chapters are missing from national history. We lacked not writers, but discipline, coordinators, teams.

Among histories, I have always favored that of V. A. Urechia—built from documents: decrees, sales contracts, wills, and many others, through which the real force of people becomes visible.

Beyond those already published, there are many documents that have never seen the light of day, slowly fading in the deposits of the archives. Among those who care for them—doing all that one human being can to preserve and even copy them—is my friend Claudiu Turcitu.

From the outset, I must say he is no ordinary person, as one might assume, but a true erudite. He knows medieval Turkish and Greek (both modern and ancient). He reads Slavonic. He handles Latin with ease. As for modern languages—it hardly bears mentioning. He is an archivist and historian, specialized in medieval history, at the National Archives.

One morning I woke up thinking about him. And I will tell you why.

Among the papers I was rummaging through, I came across a name that ignited an interest impossible to put to sleep. There are days like that, when a seeker’s frenzy takes hold of you and refuses to let go. For me, this was the day I encountered the name Gheorma.

Do not ask me what I was looking for—I no longer remember. It was during the time I was writing The Phanariot Manuscript.

What matters is that today, finding this character worthy of pursuit, I have decided to write here, as I learn more about him—naturally, with the invaluable help of my friend Claudiu Turcitu, guardian of manuscripts.

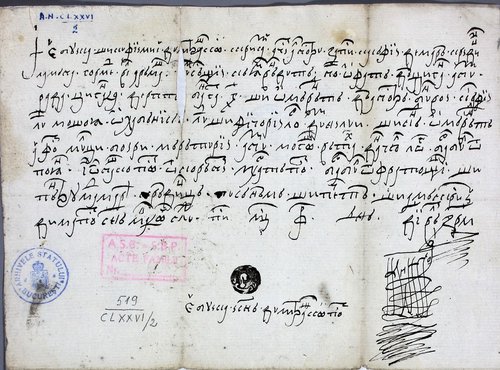

Everything begins with a document recording the conditions of a “purchase.” It was written in the year 1632—and I reproduce it here, so you will not think I invented it.

This sheet of paper, folded for a long time, perhaps hidden in a leather folder or simply among other similar papers, has survived to this day. Through this document, a vel armaș named Gheorma purchased a woman.

It was February 14, 1632, and the transaction took place near Craiova. The throne of Wallachia was then occupied by Leon Tomșa (1629–1632). Deposed in the summer of 1632, Leon was living the final months of his rule. During this time, people managed in many ways, among them the trade in human beings. We are at the beginning of the seventeenth century, a flourishing period for slave traders.

Thus, on a cold February day, Gheorma the armaș buys a woman, as he might have bought a carriage, a horse, or an ox.

To understand this properly, it must be said that at the time an armaș denoted a princely office or, more generally, the profession of an armed man. In 1632, a vel armaș was a high-ranking official. In Wallachia, the armaș could oversee the army’s artillery, but more often he was responsible for princely prisoners—state slaves. Gheorma was such an official, of the first rank, typically charged with supervising prisons and capital punishment.

His name appears on many other documents proving his involvement in this sphere of executions. He was not exactly an executioner, but he certainly decided who was punished and how. And at the time, the imagination of coercion was prolific: the guilty were beaten in public (with switches, whips, or clubs), sent to monasteries (with little food and much labor), dispatched to the salt mines (from which they were rarely released even after their sentence expired), or hanged at Obor. Poisoners—considered the most loathsome criminals—were stabbed and thrown by the roadside. Gheorma was the man who enforced these punishments, decreed by the Divan, the Metropolitan, or the police authority.

He must have been young, judging by the many documents bearing his name across subsequent years. As an armaș, we should imagine him dressed militarily, his chest covered in braids and ornaments, with a silk sash around his waist and, above all, a silky cap of atlas fabric, discreetly trimmed with fur or velvet. Judging by contemporary portraits, he would also have worn a surguci—a small pompon fastened to the cap with a brooch. Though a princely ornament, it could be imitated by other social categories in a humbler form.

He was young, then, and held a good position. Executions depended on him. A number of unfortunate souls were at his mercy, some of whom occasionally escaped—if they guessed the right price for officials and police.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, although social arrangements differed from those of today, general psychology did not differ much, nor did life’s main aim: to gain social rank, money, and—ultimately—a bit of love. Gheorma was well equipped to build a social ascent.

His life begins with this document, through which he purchases a woman, sold at a fair price by a man named Buicca, himself pressed by need.

What happened next, I will tell you next Wednesday—after I read a bit more.