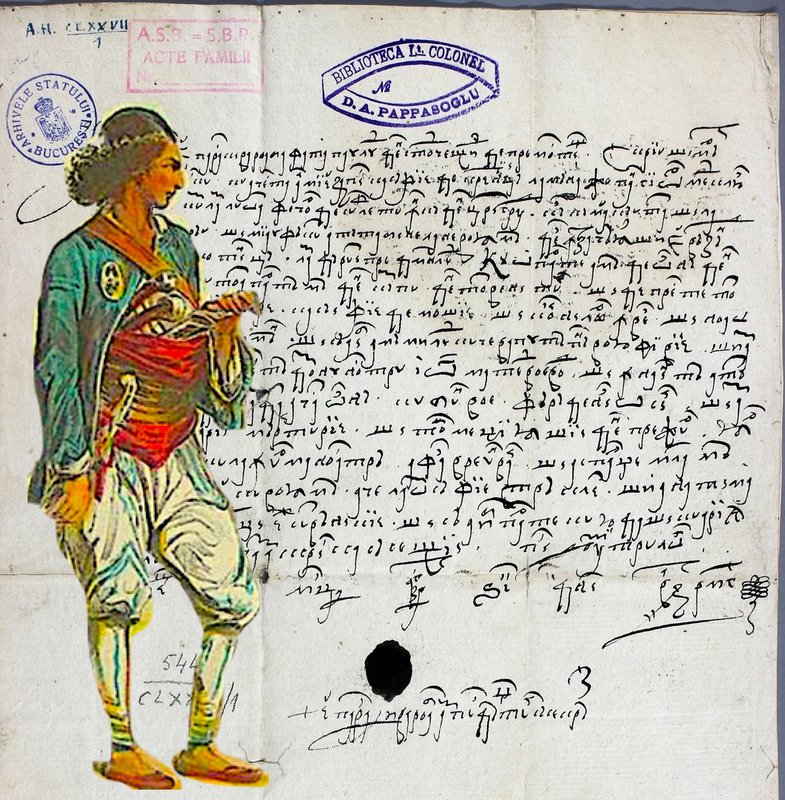

On Saint Mary’s Day in the year 1635, an elderly woman and an imposing man step down from a carriage. They have traveled a long way, for they have business at the Princely Divan. Matei Basarab sits on the throne, and although it is a feast day, the boyars have gathered at the Palace to hear petitions and ratify various acts. The two visitors are Paraschiva and Gheorma. They have come “before Lord Matei Voievod and before the entire Divan,” because Paraschiva must perform an important gesture: to place her finger mark, “so that it may be believed.”

Among the documents connected to the rise of Ban Gheorma, this one stands out—a donation with testamentary value, sealed on August 15 at the Palace.

Paraschiva, from Stoicești—a village that still exists today, halfway between Craiova and Râmnicu Vâlcea—has made a journey to the capital. Imagine it: summer, and beside her Gheorma, whom she loved boundlessly. Both were dressed in their finest clothes: Paraschiva wore a beaded diadem in her hair; Gheorma, as I have said, loved green—the color of cabbage—and, adding a detail of my own, he wore a finely embroidered vest adorned with thirty small buttons.

Many years earlier, this woman had gifted him half of her estate; now she leaves him the other half as well. It is the year 1635, and Gheorma has only just become clucer, a minor boyar title that came with many expenses.

The deed of donation is impeccably written, on half a page, well preserved. Claudiu Turcitu transliterated it for me and published it on the website of the National Archives. I reproduce it here as well.

From this brief document we learn many things. First and foremost, that the slave trader—future Ban Gheorma—was an adopted child. Paraschiva had brought him from Istanbul many years earlier.

But who was this woman, and what had she been doing in Istanbul, given that few women dared to undertake such a long and complicated Balkan journey? She signs simply as Paraschiva, without any boyar title, adding only this for identification: roabă—a slave. Therefore, she had been enslaved, though clearly freed by then, since she owned a small estate, an ocină, important enough to be divided in two.

It is possible she had owned this property before becoming enslaved, since people of some means were often kidnapped and sold. In a document from roughly the same period, a minor boyar complains that thieves attacked his household, set his houses on fire, abducted him and his entire family, and sold him in Vidin. Through an adventure worthy of its own telling, he managed to escape and asks Brâncoveanu to restore his rights, since all his documents had burned. A similar fate may have befallen Paraschiva.

Arriving in Istanbul, she met Gheorma as a child, perhaps already an adolescent. Somehow he helped her escape and return home. She may have acquired her property in other ways as well—for instance, being endowed by a master who freed her. According to the Code of Armenopoulos, if a master died without heirs, his slaves became free. Sometimes masters granted property deeds, especially as dowries for girls, particularly if the girl was the boyar’s illegitimate daughter.

We know that Paraschiva was not born in Stoicești, but was the daughter of a man named Pau, from a settlement called Moicești, near another estate—most likely a sălaș, now disappeared. This makes me inclined to believe she reached Istanbul after being sold. Perhaps she spent some time there as a servant or in a harem, from which she managed to escape, helped by Gheorma.

In any case, to own—and above all to keep—an estate required strength and a highly complex life experience.

Between Paraschiva, the former slave, and Gheorma lies a dark and ancient story. This is why she feels compelled to justify her donation: “so that it may be known that I took him as a son of the soul in Constantinople, and that he sought me in good times and in bad, and did me much good in my need.” There is here a sense of moral debt, even admiration, for a little further down she describes Gheorma as a man of “great judgment.”

And indeed, his ascent is remarkable. From a “child of the soul,” gathered in Istanbul, he becomes a grand ban, owner of inns, with wealth and houses in Bucharest.

Their journey back to Wallachia must have been unforgettable, and Gheorma was certainly familiar with the lives of slaves. Perhaps they lived in the same quarters, under the same master. Perhaps they earned money together. Both had known slavery. Precisely for this reason, he entered the trade in human beings early on. He knew the field well. He had seen much; he knew the price of freedom.

From a young age, he entered service as armaș, responsible for princely prisons—that is, again, for slaves. To set him on his path, Paraschiva gave him half of her estate. We do not know exactly how large it was, but the other half she leaves him is described as “all my share of the fields, of all income, and of the entire boundary, as it shall be determined, to be his estate.” It was arable land—fields—extensive enough to merit the name of estate.

Paraschiva was old now. That is why she specifies that for as long as she lived, Gheorma would care for her. Perhaps she had relatives; perhaps there were complications, since a simple will was not enough. Most likely the adoption had never been formalized, and both knew how many injustices occurred in the world. That is why they chose a secure act, sealed by the ruler and the Divan, upon which Paraschiva placed her finger mark—dăcitul—with such force that, looking at it today, after centuries, it resembles a black hole. A gate between worlds.

The trade in human beings began with this estate, transforming itself into offices and ranks. Every person cherishes freedom, which is also the easiest thing to lose, for all ascents are built on enslaved people, forced to spend their entire lives working for another—or fleeing, changing masters.

Paraschiva remains a slave to the end of her life, while Gheorma becomes a grand ban. They share a common experience—one that terrified her and offered him a model. In the end, only the man holding the whip is free, and not even he entirely.

Here ends the story of Gheorma—the slave trader (not to be confused with the other Ban Gheorma, killed by mercenaries)—who died a natural death, leaving behind two sons, the title of ban, and a church remembered by Bucharest for centuries. I even made him a character in The Phanariot Manuscript. No one knows how many slaves he sold. No one knows their names or stories. And we would not have known Paraschiva either, had she not placed her finger mark.