On a pandemic Christmas Eve, I feel like closing the year with a tribute to doctors—praised and vilified with equal fervor. Old documents often mention them, portraying doctors at times as luxury slaves, at other times as servants without rights. When I think of doctors of the past, Pisani comes immediately to mind—the one I wrote about ten years ago, the doctor kept in a cage, dragged in chains from Iași to Bucharest, tortured and killed. Only after that do I think of the impostors who posed as doctors, “foreigners” thrown across the Danube and forbidden ever to set foot in Wallachia again. And then there is Fârțogul, about whom I wrote recently.

But among them all, one man named Radu seems especially worthy of mention, as an homage to this thankless art.

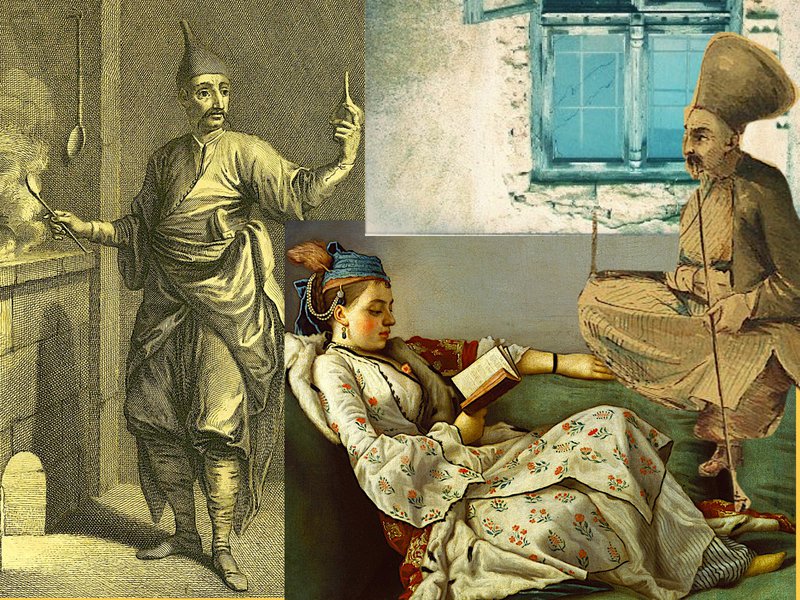

In the year 1794, Radu is the son of a widow from Bucharest—a young man freshly returned from Europe, who had boldly set out on foot from city to city, crossing so many countries that no one bothered to list them anymore. He is smiling, dressed in eccentric clothes—neither German nor Oriental—and often draws attention because of a funnel-shaped hood. No one mentions his ancestors’ names, nor even that of the widow from whom he had, no doubt, inherited both a taste for adventure and perhaps an inclination toward medicine.

Then, as now, people of ambition found one another easily. Radu befriends Isac Ralet, whom I consider a genuine writer, hidden beneath piles of official paperwork. I must say at least a few words about him.

Although histories claim he came from an ancient Italian family that reached Byzantium and then our lands, I would rather say he rose from the Jewish quarters of Bucharest, judging by the pure Romanian in which he writes. Around 1794 he still signs simply Ralet, with a single l. He is the first in a boyar family that he himself founded. Many princely documents—especially from the reign of Alecu Moruzi—bear his hand. He writes vividly, with memorable portraits and atmospheric detail; you recognize his notes by style alone. He must have been charming, and to that he added intelligence—two gifts that won the heart of Nastasia, Princess Ghica. After marriage he became vornic and then grand ban, and thus began the fabulous history of his family of “Hellenized Italians.” His descendants added a second l to the name. In truth, Isac Ralet could be whoever he wished. His literary talent was inherited by his son Dimitrie.

At the time, Isac is young and writes petitions, summaries of investigations, and findings he himself conducts as a Palace official—an inspector of sorts, a post reserved for boyars or those with documents proving honorable social status.

You may recall how I often tease Alecu Moruzi for his prodigious writing. In reality, many of those documents are Isac’s work. At first he signs only with his name; later he adds titles—another sign that in 1794 he was a young, intelligent, educated man, clearly a native Romanian speaker, perhaps protected by a boyar family.

Radu, freshly returned to Bucharest after roaming Europe, befriends him. He carries a certificate stating that he had served under a doctor who taught him the trade and issued him credentials. We do not know the doctor’s name, nor the city—details that hardly matter, since Isac himself vouches for him.

The occasion that brings Radu to the Palace is as dramatic as it is miraculous—fit for telling at Christmas.

At the time, a woman named Gherghina lived in Bucharest, an avid reader fluent in many languages. She haunted shops in search of books and manuscripts brought from who knows where. Though she had once inherited some means from a merchant uncle, by 1794 she was destitute. As if that were not enough, she fell victim to yet another calamity, prompting her to write to the ruler—so to speak—since her impeccable petition was written by Isac himself.

This woman, who knew Erotokritos and Aesop by heart, was condemned to die: alone, without income or relatives. Perhaps from too much reading, perhaps from a curse, she had developed curtains over her eyes. She could no longer find doorways or streets; as Ralet writes, she bumps into all the walls like a log. She was blind—more precisely, she had cataracts, curtains over both eyes.

There was, however, a solution, which Ralet now records in his own name. But he was not the sort to move his pen without ensuring its value. First, he devised an experiment.

Having just befriended Radu—after many evenings of conversation, the kind where eyes spark and blood races through every vein—after sharing dreams and swearing to renew morals, Isac plans the experiment that would change Radu’s status and place Gherghina at the center of attention.

It is August, and Bucharest has closed its gates because of the plague. Weeping, Gherghina—accompanied by a small retinue of corpse-carriers and soldiers, watched by eyes pressed to windows—is led from Colțea straight to Lipscani, to Radu’s house. Tall, wrapped in beads and veils, wearing a pale dress from which small bouquets seem to flutter—she was unforgettable. Anyone who saw her could swear she was blind; anyone who did not saw her nonetheless knew every detail of the journey.

For a month, the blind reader is treated as if in a luxury sanatorium: housed, cared for, given medicines purchased by the young doctor who knew how to cure cataracts.

And then, in September, a miracle occurs. Gherghina is healed, her sight fully restored. More beautiful, ready to open a book again, she passes once more through the city. People again press their noses to windows; dogs bark; guards announce the event from watchtowers. The doctor is praised—but all eyes turn to the Palace, for nothing memorable truly counts unless the rulers take part.

Only now does Ralet write the entire story to the prince. Gherghina walks the streets praising not so much Doctor Radu as the ruler himself. The description is detailed; the story rises in crescendo, from the reader’s wretched state to the recovery of sight and the fanariot prince’s glory—upon whom the whole city expects the cost of the experiment to fall. The city is stunned; some even venture out of their houses for the occasion.

Thus, as a party implicated in the story, Moruzi has two things left to do: pay for Gherghina’s treatment—thirty talers—and order Radu’s employment at a hospital, with a monthly salary.

And that autumn, alongside plague and weddings, Bucharest acquired a curtain doctor, duly certified—though no one quite knew what the certificate said. But what did it matter, compared to Gherghina’s miracle, attested by Moruzi and inscribed into history by the talented hand of Isac Ralet—future vornic and ban, but above all a prose writer ignored by literary history, whose name survives thanks to documents written in Cyrillic script.