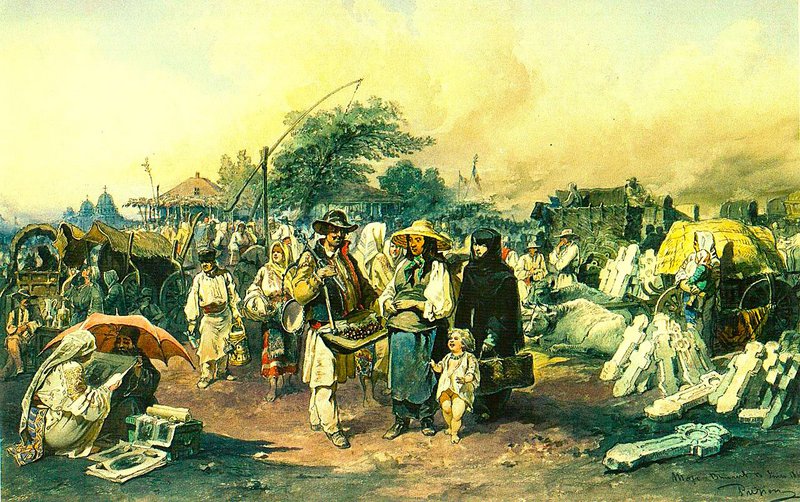

In a painting by Amedeo Preziosi (1816–1882), reproduced here, we see an ordinary fair held on Moși, at cherry season—something made clear by the itinerant cherry seller placed at the center of the canvas. Around him: familiar details, from stone crosses to the sour-cream vendor on the left. I hope you notice the small mug tied to the churn—a measuring tool, but also the very vessel from which eager customers would taste the goods, with no concern whatsoever for COVID or anything of the sort.

The covered carts resemble today’s mobile stalls or caravans, while nearby a woman recovers her spirits by tossing back a shot of brandy she paid almost nothing for. A mountain woman, accompanied by a child and a nun, scans the scene for bargains, sheltered by a straw hat.

And finally—the monk.

Holding a small umbrella in a peach-pink shade, a pretentious and extravagant color, known by a word of Neo-Greek origin that entered Romanian via Turkish: pembé. According to Mianda Cioba, in a scholarly study on colors, the word entered Romanian around 1845. So we can safely say that the monk’s umbrella was indeed pembe.

Crouched with a certain elegance, the monk sells icons and other portraits—or perhaps simply engages in conversation with a woman interested in a painted likeness. From the way she examines the piece, and from the eloquence stamped on the monk’s face, we can tell that he is the merchant, perhaps even the painter himself. What was a monk doing at a fair, selling portraits painted—judging by appearances—on thick, handmade paper? Where and how had he painted them?

Monastic life was never easy. Do not imagine him sitting peacefully in a cell, dipping his brush in paint. Monasteries often took in abandoned children, the defenseless, freed slaves without masters, artists, born wanderers, the punished, or those being prepared for death.

In 1794, a dandy from Lipscani Street—a neighborhood constable, as we might say today—was caught with the wife of a harem administrator. A scandal erupted, ending at the Palace, where the prince punished the lover by sending him indefinitely to Snagov Monastery, to pray for forgiveness. This was a common way of becoming a monk. He must have endured quite a bit, though given his familiarity with Lipscani, he likely found a way to escape eventually.

Around the same time, in January 1794, a priest from Teleorman, together with his church warden, entered into petty business deals with market women who were to sell goods at the fair. But a man of the Church had no business degrading his rank with such profane activities. Once the affair became known, both priest and warden were sent to Cernica Monastery for two years “to learn their lesson.” I suspect those years were hard, and I doubt they ever tried to leave again, hoping instead to regain their parish by not angering their superiors.

Monasteries also sheltered thieves, men sunk in depression, and all sorts of social outcasts—especially now, in what we might call the era of the Adjective Policeman, it is hard even to speak of them.

Monks, then, came from diverse backgrounds. In poorer monasteries or those led by indulgent abbots, many monks left during the day, roaming the streets, especially fairs and places of entertainment. Bucharest held weekly markets, and every major summer feast brought new fairs with countless attractions. Toward the end of the eighteenth century, a troupe of French actors even received permission to perform at fairs, particularly at the great feast of Saint Mary. Sword swallowers, fire spitters, bearded women, giants and dwarfs could all be seen there. One could sample brandies and liqueurs, eat delicacies—sweet fritters and doughnuts ranking first among them.

Why, then, should a monk miss such a complex spectacle?

Sometimes, when their monastery was strict, monks left for good. A monk like this one might find shelter with a kind host, in a stable or an orchard, painting by the edge of the fair during the day and wandering the fairgrounds at night. He could have been a traveler, an artist hungry for adventure, or a genuine monk sent by his superiors to sell icons. The first option seems more plausible—and here is why.

Toward the end of the eighteenth century, the poet Ienăchiță Văcărescu noted the emergence of a new social category: vagabond monks. Frankly, I would not have expected such narrow-mindedness from a libertine poet—one I portrayed quite sympathetically in Zogru—that he would ask the ruler to round up all wandering monks. And yet Moruzi listened to him. A decree was issued, and monks were forbidden to leave their monasteries without a written permit—adeverință, the exact word used—signed by the Metropolitan.

At this point I begin to feel related to these cassocked adventurers. I could almost weep thinking that they had no internet to obtain permits instantly. Instead, after days wasted in the Metropolitan’s courtyard, through petitions and bribes, they might finally secure a scrap of paper granting free passage. Thus arose forgers specializing in travel permits for monks.

In any case, monastic vagabondage did not disappear. Proof enough is our monk—emancipated, an artist, a trader in paintings.

And now, back to the umbrella.

That pembe shade, bordering on the ridiculous. That frivolous color carried above the crowd. A monk with a pink umbrella was more scandalous than a drunk woman, more suspicious than a street performer, more unsettling than a thief. Not because he sold images, not because he wandered, but because he dared to decorate himself. Feathers, colors, umbrellas—these were never innocent. They were signs. And in a world obsessed with control, nothing was more intolerable than a man of God who allowed himself ornament, whim, and shade.