The most striking quality of Doina Ruști’s writing, visible across all her books, is the imaginative verve from which her stories are woven—the inexhaustible energy that gives birth to characters and narrative threads. Although shaped within the conventions of the historical novel, Ruști’s prose uses historical hypotheses as pretexts for exploring fantastic scenarios, blending fiction and metafiction into an alloy of magical realism that brings her close to the great South American masters, with whose work numerous correspondences may be drawn. The fabulous stories in Zogru, The Book of Perilous Dishes, The Ghost in the Mill, or The Phanariot Manuscript are, almost without exception, also stories about the act of storytelling itself—subtle metanarratives on the nature of fiction, its status, and its relationship with reality.

The historical framework of Ruști’s novels is in fact only generic and approximate, allowing the narrative to leap easily into a kind of ahistorical, magical time, in which a world of overwhelming authenticity comes to life. Here lies one of the paradoxes of the magical fiction she creates: the more elaborately her ink-and-paper worlds are wrapped in imagination, the more frequently their realist logic is short-circuited by superstitions, legends, and spells, the more pronounced their sense of truth and authenticity becomes. It is as if fiction itself were generating truth, as if from its sap a world were taking shape that is even more real than reality.

Naturally, this powerful reality effect is the result of the extraordinary rigor of Ruști’s documentation for each book. One is inclined to see her as one of the most knowledgeable researchers of the Romanian world of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, at the very least, studying archival documents and historical writings with meticulous care—whose cosmos is then brought back to life through the creative power of fiction.

The sense of immersion in a bygone Romanian everyday life is consistently overwhelming in Ruști’s work. She is among the very few writers capable of generating virtual worlds of astonishing consistency: streets crowded with people and stalls of every kind, workshops, merchants, officials from across the Levantine world, arnauts, revolutionaries, priests, conjurers, coachmen, and spiritualists—a motley mixture of oriental and occidental elements whose semi-real bustle is rendered cinematically in the very code of the writing. It is a Levantine world of unsettling picturesqueness, one in which magic and the fantastic are naturally embedded in the logic of events, where anything is possible. Represented through luxuriant imagery, with exceptional mastery of setting and impeccable narrative direction, this world subtly conceals its narrative devices, the entire epic scaffolding, and the complex mechanisms of the text. The epic force and solidity of Ruști’s prose—often noted by literary criticism—are felt above all in this capacity to generate a complete reality effect, a revelatory experience of imagined historical episodes that fiction accredits as fully plausible, comparable to authentic reality. One can also sense here the author’s training as a screenwriter, in the confident cutting, handling, and linking of sequences—so that virtually every book by Ruști appears immediately adaptable for the screen.

To all these literary assets is added a style of singular refinement—magnetic and hypnotically seductive—sustained by a dazzling baroque language. In Romanian prose, Ruști’s stylistic charm finds competition only in the work of Mircea Cărtărescu or Ștefan Agopian. Her novels are true linguistic spectacles, naturally combining contemporary vocabulary with archaisms into a perfectly coherent construct, free of dissonance. Many passages carry a strong poetic charge, exploiting to the fullest the expressive resources of words and their imaginative force. It is no wonder that critics have written of The Phanariot Manuscript as if it were a long poem. This entire fictional cosmos—authenticated through topographical, ethnographic, and sensory precision—is bathed in the waves of a discreet yet omnipresent empathy: a melancholic, identificatory empathy, at once distant and analytical, that the author extends toward the world she creates.

This Phanariot Bucharest, composed of the materials of dream and historical imagination and granted the highest degree of reality by Ruști’s prose, becomes a bewitched analogue of today’s Bucharest—the city we know, with its daily vices and habits, its illusions and bovarism, its glimmers and shadows, its improbable characters, urban myths, and mental blockages. In this sense, Homeric and The Phanariot Manuscript reveal, in palimpsest, the city’s archetypal maps, its tangled genetic code, and the subtle equations of historically shaped identities and mentalities.

The action of Homeric, Ruști’s most recent novel, is likewise placed in this legitimized imaginary territory: a magical Bucharest submerged in vaguely defined Phanariot times, whose everyday cosmos is nevertheless reconstructed with maximum authenticity, relying on the reality effect described above. Particularly visible in Homeric is the Eliadean strain of Ruști’s writing, even as she works with the tools that have already defined her, constructing a polyphonic story around the Gorgan neighborhood and the ancient Cotroceni woods, inhabited by fantastic beings and fabulous plants such as devil’s blood, the flower of divination that opens passages to the other world.

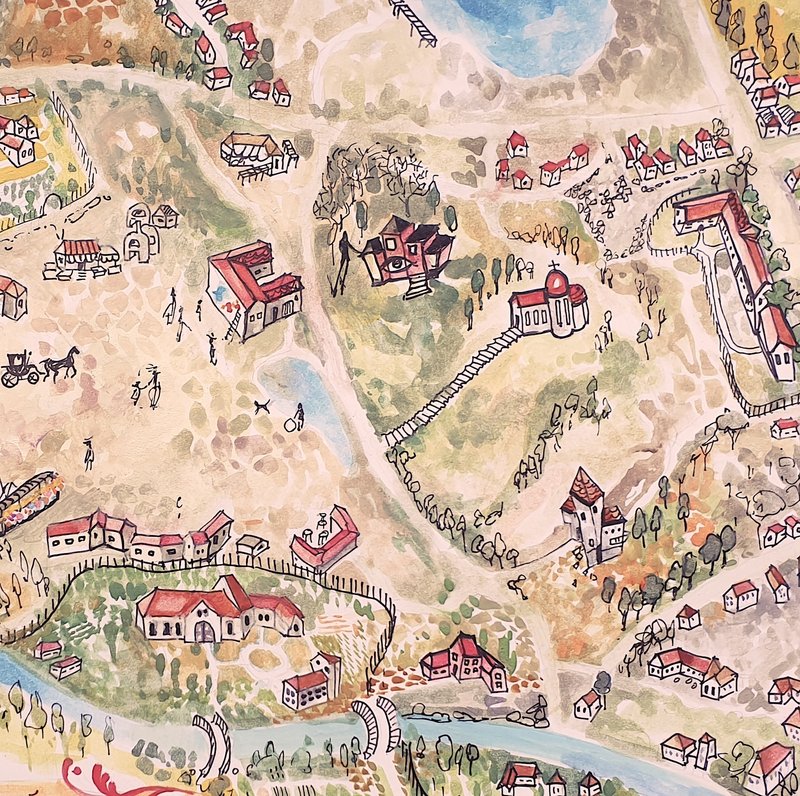

The space in which Ruști situates the story of Homeric is a kind of infra-real Bucharest—it is and is not the historical city as we know it, even though its topography coincides with the real one. As in other novels by the author, the book is accompanied by a map, on which the story’s topoi are superimposed onto the city’s present-day geography, much like the 3D layers of a virtual reality arranged on a strategy game map. In itself, the map is a manifesto of Ruști’s poetics: a document authenticating an imaginary world—an alternative world, certainly, but no less true than the one recorded by official history. Here we find the Merchant Dura’s Lake, near which the future Cișmigiu will emerge, its waters inhabited in Homeric by a pagan spirit; Cotroceni Road, Brezoianu Street, Podul Mogoșoaiei, Schitu Măgureanu, Lipscani, and the Dâmbovița River, dotted with mills and crossing diagonally boyar estates, monastic lands, and settlements surrounded by a legendary aura.

The Gorgan neighborhood—the axis of this legendary world—is a magical place, comparable, as Gelu Diaconu has observed, to Macondo in Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude or to R. K. Narayan’s Malgudi. Essentially, Homeric stands at the border between fairy tale, fantasy, and historical fiction, insofar as all these modes remain anchored in reality and take on accents of detective fiction with noir inflections. The story unfolds slowly, through carefully orchestrated discontinuities, skillful narrative pauses, and moments of necessary reflection. As in all her books, Ruști writes with a precise vision of the whole from the outset, leaving nothing to chance or to momentary inspiration.

Homeric does not evolve, in a Cărtărescu-like fashion, through an uncontrollable autonomy of the text that generates itself like a spider’s web. The place of each element is rigorously predetermined, as are the temporal structure, the sequence of episodes, the evolution of characters, and the inflections of the narrative voice.

At the center of the novel lies a love story between Despina Băleanu and the “painter” Pantelimon Iorga, who, in the midst of a midlife crisis, abandons his wife and children. The affair quickly becomes the neighborhood’s social gossip and the catalyst for a collective agitation that brings mysterious disappearances, an equally mysterious murder, and a fatal entanglement in a complex web of conspiracies, lies, and typically Balkan superstitions. Notably, even though the fantastic elements are demystified in the final chapters through a demythologizing narrative voice, the conviction that this world—saturated with the aromas of fiction—remains under the sign of the fantastic persists. In this sense, demystification itself amplifies the sense of the fantastic, offering yet another demonstration of Ruști’s narrative power.

From the Brownian humanity of the story emerge numerous memorable figures—Ciptoreanca, Mărmănjica, or Năltărogu (the last descendant of a race of giants, recalling Egor from Cărtărescu’s Nostalgia, as well as the character capable of becoming transparent in a novel by Radu Vancu), Captain Manciu, the boyar Băleanu, Scarlat Filipescu, and others.

Homeric stands as one of the most fascinating prose works of recent years—written with erudition and the literary technique of a jeweler, a kind of metatextual manifesto on the enduring power of Story, on the ineffable beauty of fiction, and on its capacity to rival reality in authenticity.

*Full text: * here

On cover: a fragment from the map of the novel.