Everything began behind Saint Sava Church, where at the time there lay a garden of weeds, the remnant of an old cemetery. A few ancient stone crosses were still visible. There, beneath a blueberry bush, began the immortal life of Elina, the cap-maker’s wife.

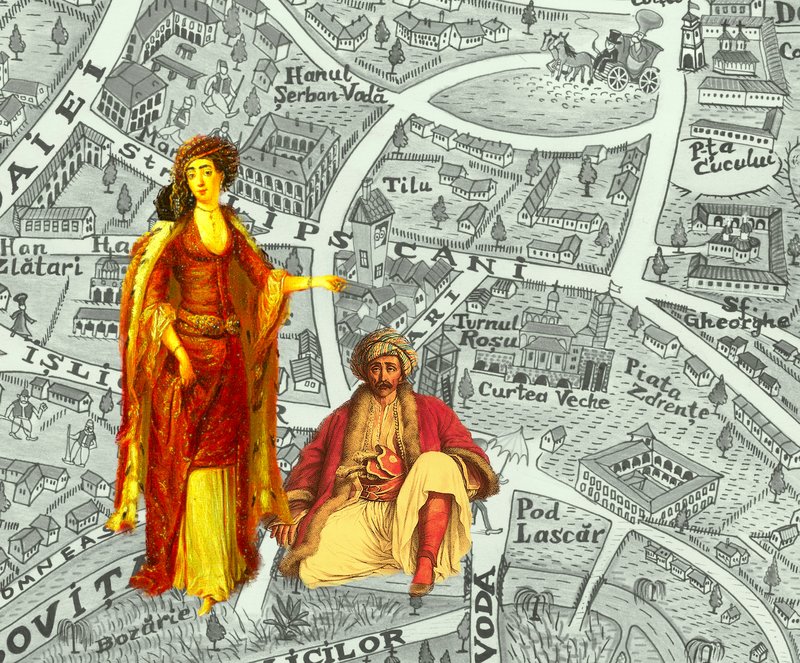

Married only a few months, this woman—who through her deeds would draw a map of rare pleasures—made daily journeys across the city, for her husband was a celebrated maker of ișlic hats, so devoted to his craft that every cap from his hands was a masterpiece, a rare object. He made chiefly globular ișlice from broadcloth in every color, but also from fine leather dyed with artistry, from thick silk, even from hemp sweetened with a single thread of silk. He owned an excellent wooden mold, balloon-shaped, over which he stretched any material to perfection. When the work was finished, Elina would load the carriage with monumental ișlice and deliver them to customers, collecting the payment with infinite pleasure—mostly silver coins, but also thalers or second-hand para, all good money, sorted by value into cotton or leather pouches, or slipped directly into the pockets of her skirts or into her bosom.

Yet this perfect life bore a crack.

One day, Elina had to deliver an order to Saint Sava, for a schoolmaster. To shorten the way, she stopped the carriage near the church and, dragging after her the basket in which a single ișlic reigned, cut through the weeds. And somehow—under the sun of a day thick with temptation, perhaps guided by a fairy’s finger—Elina suddenly found herself face to face with a man.

He was dressed in silk, a figure fallen from the sky, and to reinforce the impression he began to speak in a mysterious language. Elina stood frozen, staring at the stranger’s lips as they shaped bizarre words. Then the man took out a ledger and began to draw. His hair, tied in a tail, had slipped behind his ear, and his eyes shone lupine beneath the shadow of a rather floppy fez.

Elina stood there for a while, but when the man gestured, she approached without a trace of modesty. On the white page he had drawn her portrait exactly as she stood, one hand resting on the basket. There was something inhuman in the entire encounter. The tall hollyhocks, the hemlock, and the surrounding bushes made everything seem detached from real life. What followed was spontaneous and almost mystical: a swift union beneath the blueberry branches. Several hollyhocks snapped, the man’s fez rolled toward the fence, and Elina lost a tassel from her shoe.

When she emerged from the churchyard, she was no longer the same being, and the event ascended into the sky among those deeds that never die.

A few days later, she stopped to buy some thread from a street vendor. He told her he had more goods at Chiriță’s Inn, where he also lived, and Elina offered to accompany him. The corn-seller was shocked, but felt it was not his place to judge her.

The inn room was like an eye over which a fragile eyelid trembled. Through the barred windows one could see the crowns of linden trees, while on the bed the shadows of subtle beings drifted lazily. What had begun as a small transaction became a passionate struggle. The floor was carpeted with Elina’s many skirts, while the man’s șalvariended up on the windowsill. Nothing she had lived before compared to that afternoon, presided over by a faun. The needle-and-thread seller melted within an hour and, in his new state of milk and honey, slipped slowly beneath the skin, dissolving into the vast territories of heated flesh.

The next day Elina panicked, tormented by questions of duty and guilt. In this state she entered Barbers’ Street to deliver some ișlice. When she finished her business and was returning to the carriage drawn up at the edge, she noticed someone watching her. A man leaned against a wall—wide-eyed, somewhat scrawny. She meant to ignore him, but from his lips slipped a melody, softly whistled, as if by the wind. She glanced again, and the man—now clearly seen—held a cane with a silver handle and gestured for her to come closer.

He had not spoken; he was surely a rogue. And yet Elina’s legs seemed bound to him. With small steps that at first glance suggested hesitation, but were in truth besieged by emotion, she reached a gate. From the balcony cascaded a curtain of honeysuckle, and from the garden came the cry of an angry cuckoo.

Elina lingered many hours in the stranger’s house. The curtains were drawn, and in the dim light the man seemed made of tobacco smoke. Later, in the many nights that followed, she no longer remembered his facial features, but she remembered everything else. She had no doubt that the man from the honeysuckle house vanished together with her desires.

From that day on, the city’s geography changed for Elina. From the swarm of people, the heap of houses, and the countless streets, only three places remained that mattered. Though she met other men afterward, none were granted entry onto the secret map. In the sweet world of pleasure and excess, life continued to pulse at Saint Sava, at Chiriță’s Inn, and on the immortal Barbers’ Street.

(Doina Ruști - din Depravatul din Gorgani, ed. Litera 2023)