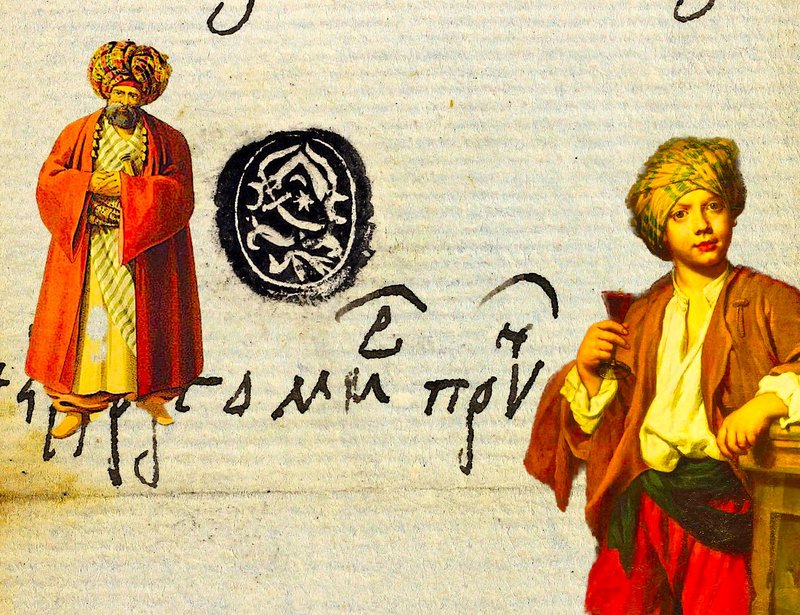

Sumptuous garments, sable collars, fur-lined vests, and above all hats of every kind—globular ișlics made of astrakhan lamb, comănac caps of marten, fox-fur hats with domed tops of broadcloth, fur-trimmed fezzes lined with silk, Siberian cat pelts used to adorn collars, hems, and cuffs—all these were made by Negoiță, a young man who owned a shop at Hanul cu Tei, where each day a collar or a modest fur garment fluttered in front of the door.

The shop also served as his home, with several storage sheds at the back of the courtyard and a workshop where Negoiță cut and sewed furs, assisted by three journeymen and five apprentices. Above the workshop was a quiet attic where the furrier would regularly retreat to design new models, smoke a pipe, sip a good wine—and indulge in another pleasure: reading.

His favorite book was The Alexander Romance, recounting the marvelous victories of the Macedonian conqueror that had rendered his name immortal. Negoiță was so attached to this book that at times he would stroke the letters themselves, delighting in the vivid illustrations—motifs that reappeared on his garments, especially on white lambskin vests embroidered with the incomparable hero’s silhouette.

One day the book disappeared. He found it only with great difficulty, buried under a pile of furs in the workshop—a deeply suspicious place. Terrified at the thought of losing this joy, which meant more to him than fur-making itself, he decided to protect it. Summoning all his employees, he wrote a curse inside the book—a curse that would survive into our own days, a few lines as immortal as the hero himself:

Should anyone steal this book, may they be cursed by three hundred saints; and should anyone borrow it and lose it, or refuse to return it, may they be cursed so that their body never decays after death.

He signed it, of course.

The journeymen looked on gravely. The apprentices stared in thoughtful silence. You might say that not rotting after death is no great tragedy—after all, one is already dead. But this was the eighteenth century, and the curse targeted a Christian soul: to remain trapped in the matter of death, unable to enter Heaven; to exist in a wretched state, crawling with worms, glued to mud. And then there were the three hundred sacred beings—enough to hang one forever at the gates of Hell.

Among the apprentices, however, was a pure Cartesian, a child of the revolutionary age of Enlightenment. He had not read Voltaire and knew nothing of encyclopedist deism, but he was attuned to the spirit of the age by instinct alone. And so he snatched the book.

The apprentice was not a reader. He wanted to mock the furrier, to challenge the three hundred saints, to prove that even such a carefully guarded book could be stolen.

He hid it under his bed, in the cramped corner of a stable annex where he slept, wearing a grin meant for the furrier, who had already roused the entire neighborhood.

“The book is protected by a curse,” the furrier declared. “Within a week—at most—it will be found, and the thief will be dead.”

To demonstrate his faith in the curse, he even threw a party, attended—naturally—by the thief himself, now growing ever more confident.

Fifteen years old, brimming with self-assurance, and a stolen book under his bed—this is the story of the non-reading apprentice.

But two nights later, a worm settled into his confidence. The book began to groan, to sigh, to rustle. The apprentice panicked. It was night; the entire house lay in darkness. Trembling, he opened the book, and from between its pages emerged tiny beings—spirits of smoke.

He fled the house, but the guardians of the book pursued him. He ran into the street, toward the Dâmbovița River, hoping to purify himself in its waters.

That night was hell. The next day he could not even thread a needle through goatskin.

A few calmer days followed, and he regained courage. But one evening, just as the workday ended, the furrier’s workshop filled with blue locusts. Terrified, he climbed onto the windowsill, shrieking wildly, frightening everyone. It became clear that something was rotten in the life of the thieving apprentice.

The nights grew worse. I will not tell you what he dreamed. His life became an endless nightmare, and at last he decided to return the stolen book.

But it was too late. The curse had reached its end.

One morning the apprentice was found dead in the middle of the courtyard, the book clasped in his arms.

The city was stunned. The book was placed at the gate for all to see, while the apprentice was thrown to the edge of the cemetery, to spread the stench of a cursed thief.

From then on, books were avoided by thieves, and written curses became ever more refined. There was no book whose owner did not inscribe a threat inside it.

Few knew, however, that the furrier was truly a man of a single book. He wished only to ensure that no one would ever take it from him. He had his eye on the apprentice, whom he considered a scoundrel. He left the book within easy reach—baited him, one might say—and when it vanished, he began slipping small doses of amanita and hemp seeds into the boy’s food.

But what does one apprentice matter, sacrificed on the altar of culture?

What matters here is only love for books—or rather, for a single book, whose incredible hero truly lived.