A man used to sing alongside other lăutari, at weddings and various celebrations. Then, one day, his master died, and he found himself a free man, since that master had left no heirs. And freedom changes roads—and lives. This newly freed musician took to the road, all the more so as he was deeply confident in his talent.

I haven’t yet told you—he was at the age of unbridled hopes, and he played the bagpipes. But not just anyhow. From the sheep’s skin bag poured out burning waves, which the musician’s fingers shaped into calls, into sighs, into the murmur of waters.

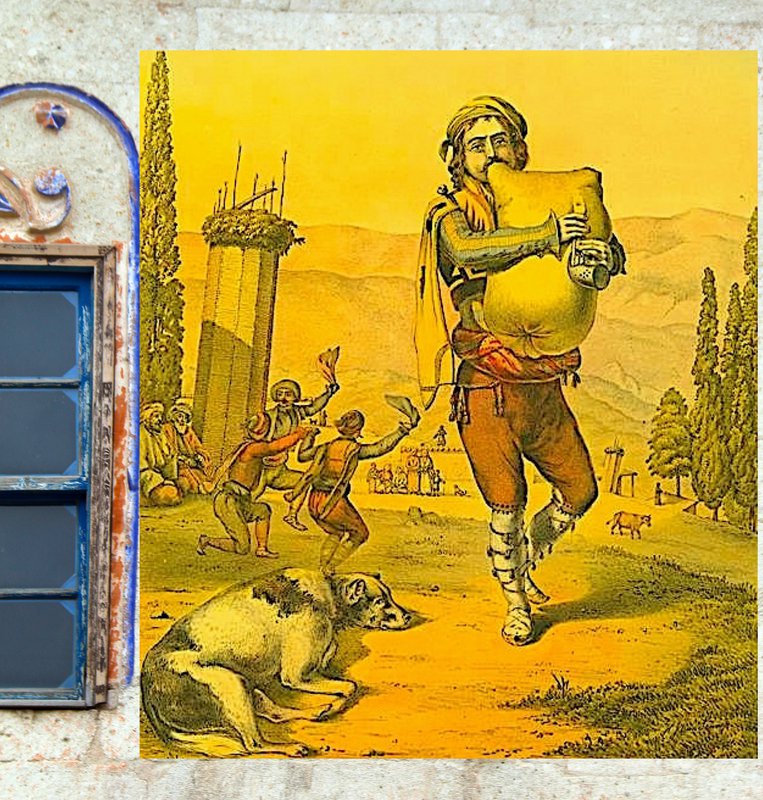

He wandered the roads playing with passion, leaving behind him dancers and rapture. There was something painful in his music, like any desire that feels unattainable, and the melodies flowed as if accompanied by an invisible rain, for the piper wore brass bells tied to his calves.

He passed through villages, and people abandoned their work and came out to their gates to dance, so that behind him, as he moved away clutching his bagpipes, one could see long lines of dancers and diaphanous scarves fluttering in the wind.

But how long can one play? How long can one embrace a sheep’s skin? Passions wither, like all things, and in time the musician lost interest. Where once he had drawn out tender trills and angelic calls, he now took it easier, and from the bagpipes—which had come to resemble a lung damp with effort and illness—each sound struggled out, crippled and labored.

When the piper stepped through the gates of Bucharest, he had grown so accustomed to routine that despair scattered in his wake. Like a sick vuvuzela, his song shrieked among the houses. Like an ambulance siren, like a drill boring through iron. Shopkeepers hid in their homes; the city police were already on his trail. Yet no one could come near this aberrant musician. The whistle of the bagpipes wormed its way into your ears like a trickle of water, unleashing disasters along its path—to say nothing of outright ruin. Some were left with ruptured eardrums; others suffered strokes. The piper had become a genuine danger, and the people of Bucharest hid in trunks and cellars, terrified by the terror that had flooded the city.

And yet the bellow could not be avoided—it was like tongues of flame in a heap of hay.

Once inside the brain, this shriek—like an owl attacked by dogs—shattered into dust, giving birth to thousands of other sounds of varying intensity: stomping feet, blows of a cane, pebbles falling on stairs.

Those who survived their encounter with the bagpipe’s scream began to utter words they had never thought before: phrases, elaborate or abrupt, sometimes poems, descriptions, declamations. Some spoke to themselves; others desperately sought a gentle listener, often dragging one by force from houses or from beneath beds.

There were also those who took pleasure in writing, in laying soft words onto the page—words born from the scream of a bagpipe. They wrote what they had disliked in life, but most often they wrote complaints, sent directly to the Palace.

Some have survived to this day, such as the petition of a tailor who writes to the ruler that he can no longer bear to cut vests for louts. His dream is another, populated by foaming garments that he believes the whole city ought to see. The ruler, he insists, would do well to raise a stage before the Colțea Tower and let his clothes fly there, to a place reached only by saints and by himself.

Others demanded impossible things: elixirs that changed the color of hair and face, flying slippers, or dancers made of honey.

Caught up in these pursuits, while the city filled with words, the piper was forgotten. He had become a ruin, still blowing into his bagpipes—a man with a vacant gaze, collapsed beside a fence. Someone bold, emboldened by rhetoric, dared approach him and found that, though dying, he continued to produce the same sound, like a threaded screw, like a lifeguard’s whistle, like the siren of Roaită.

In the end they brought a saw and cut the bag’s spout, to separate the musician from the instrument he loved.

He did not live long after that—within hours he was dead, and over the city fell once more the prosaic buzzing of ordinary life.

Still, the memory of the musician endured. There was something in his sound that had bound everyone to words. Some even included him in their prayer lists, and a merchant from Caimata paid a painter to draw, beside his window, the unforgettable silhouette of the former piper. The house perished in a fire, but not before other hands had copied the portrait, so that copy after copy reached our own days—and that is what I show here. But what can a copy tell of a man so passionately alive?