The verb to brand remained closely tied to the Stalinist era, when people would step onto balconies or public stages to denounce others. In every age, glory has meant trampling over someone else. This has always been possible — through audacity and political backing. Think of those who became writers because an emperor decreed it so. Or of that man who spent a month shouting obscenities in the street, until his name reached everyone’s ears. Only then did he say: You’ve heard my filth? Good. Now I can be anything.

During the Stalinist period, anyone eager to make a name for themselves would step forward and curse another, exposing their supposed misdeeds, revealing secrets only they claimed to know. The word for this filthy business was branding. Every honest citizen of communism had the duty to brand the hostile acts of an enemy of the people.

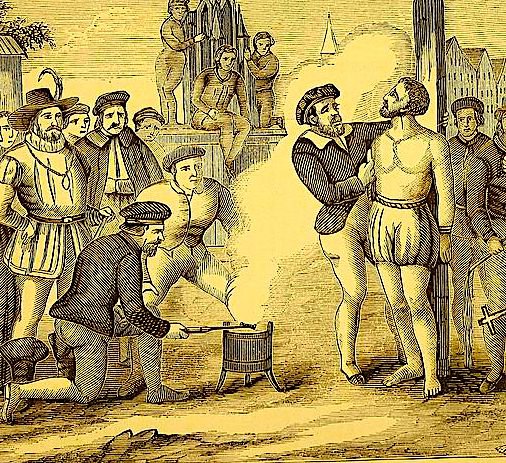

These modern meanings originate in much older times, when a guilty man — we won’t speak now of justice or law — someone caught red-handed, was dragged into the marketplace and publicly humiliated. Anyone could spit at him, throw eggs, beat him, shave his head. And to make sure it would never be forgotten, he was finally marked with a red-hot iron, a letter burned into his cheek, so everyone would know who he was and continue to despise him forever.

This is what happened to poor Iașca.

He appears in Wallachian chronicles — which makes him, technically, a historical figure. He lived in the 17th century and suffered gravely.

Iașca was Serbian, naturalized in Wallachia, a well-traveled man dressed in German fashion. Tall, well built, followed everywhere by women — you can see them, can’t you? Heavy-lipped brunettes, fiery redheads, pale blondes with thin mouths. They all dreamed of him, wanted to touch his sheets, taste his saliva. And he was worth it.

From his eyes flowed endless promises and flocks of singing thrushes. He wore his hair tied in a tail beneath an ișlic, German boots, and a small topaz earring.

Entangled in intrigues, always ready for conspiracy, Iașca had friends like himself — Western-minded adventurers, Bucharest boys, rebels and wanderers. One day they drank on Lipscani, the next they were on the road to Vienna, though they also loved Istanbul, where they were eventually caught.

Iașca dreamed of changing the world, of becoming an invisible architect of power. His friends dreamed of replacing Brâncoveanu and impaling the Turks — two utterly impossible ambitions, which they knew well, but pursued for the pleasure of conspiracy itself. Nothing is more intoxicating than plotting against another, even when success is impossible.

Iașca knew this too. He spoke recklessly in an Istanbul tavern, polishing a musket like a child with a toy. And so he was seized, accused of conspiring against Prince Brâncoveanu.

Arrested, beaten on the soles, imprisoned for months, Iașca was nevertheless among the fortunate. Brâncoveanu sympathized with him — impressed by his stature and his lucid mind. Iașca confessed: I was wrong, Your Highness.And Brâncoveanu spared his life.

The punishment was branding.

One fatal morning, Iașca was taken to the market at peak hour. His head was shaved, he was paraded through the city, mocked, and finally burned with a hot iron. The letter G — for greșit (wrong) — was burned into his cheek.

Then he was sent to the salt mines at Telega, where he spent a full year. His family intervened — Serbian nobles with money, jewels, influence — and eventually persuaded Brâncoveanu to end the punishment.

One April day, as apple trees bloomed, Iașca saw daylight again. He was still Iașca, but with lice-ridden hair and a scar carved into his face.

From then on, he was called the Branded Man.

He hid for years on an estate, trying to erase the letter from his cheek, carving other scars to confuse its meaning. When he finally accepted that he would never be anything else but the Branded, he boarded a ship to Marseille. Rocked by the sea, he prayed day and night for Brâncoveanu’s death — which eventually came.

But while generations mourned Brâncoveanu, Iașca remained forever the Branded, preserved in a page of the Anonymous Brâncovenesc and Greceanu’s chronicle. His story carried forward not glory, but a word.