At the time when I was writing The Little Red Man, my debut novel, I walked into Suțu Palace — an accident that would later become part of the book.

Back then, I was trying to build a website, an infernal task. It was 2003, the era of the mighty Composer, a program I used, among other things, to write HTML. From that entire year I remember very little, except for one day, sunny, in a season I can no longer identify. I don’t remember whether the filming for Modigliani had already begun, but I do remember that I often went to Buftea, to the film sets. I was still a lecturer at the time. That was also when I bought my first TV tuner, so I could watch the news on my computer, and when I used to buy mega-games on CD from street vendors — one of them was Kyrandia.

That same day, I had gone to a photographer. You couldn’t take photos with your phone yet. But Kodak studios had sprung up on every street, places where you could get respectable photographs developed on request, turned into JPG files, and burned onto a CD. I had just picked up one such photo of myself, and it depressed me terribly. I was working on my website and wanted to plant a photograph of myself there. But the image looked ridiculous — one of those portraits that show not who you are, but how hard you’re trying. Instead of being me, I looked like someone terrified.

In that state of mind, I entered Suțu Palace.

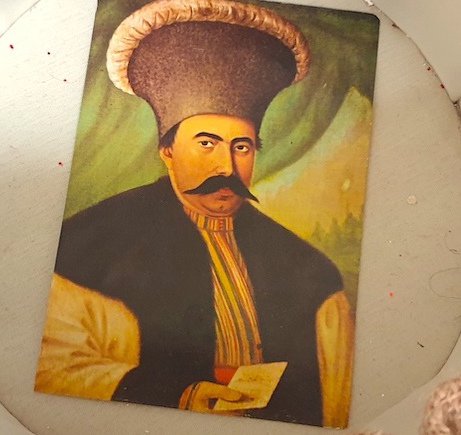

In the lobby, at the reception desk, postcards were being sold with images of the museum’s exhibits. One of them immediately caught my eye. It depicted the man shown above — a fellow who, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, was in the prime of life, a well-established merchant in his guild. His name was Aredio Sochim.

Judging by his name, he was Romanian from Istria or Dalmatia, though he probably passed himself off as Venetian or Florentine.

He wore a simple ișlic, made of wool, flat-topped and trimmed with velvet. As you can see, he was dressed in his very best clothes. The striped anteriu was made of a fine fabric called alagea, silky and reinforced with linen threads. And as for the coat — the giubea — what can I say? You can see it with the naked eye: white broadcloth, lined with fur. Clearly not everyday clothing, but garments reserved for special occasions, since white fabric was a luxury and extremely difficult to maintain.

To give you an idea: such a coat was washed rarely, only in summer, on scorching days. Most often, the lining was removed so it wouldn’t shrink. The coat was soaked in a river — always cold water — soaped thoroughly, then left to sit in the sun, lathered, for at least fifteen minutes. It was rinsed and the process repeated several times. Only at the end was it dried on a hanger, ironed, the lining sewn back in, and then placed in a chest with lavender, wormwood, and other herbs, where it slept until the next occasion — perhaps to pose for a painter.

And yet, many dowry lists include at least one white outfit, especially winter garments trimmed with fur, equally difficult to maintain and light in color. Speaking of this, I recall that Teodor Vârnav recounts his fabulous coat made of white bear fur, reaching down to his ankles, in The Story of My Life. White clothing was highly prized, despite the fact that it soiled quickly.

Judging by its appearance, I would bet that Aredio’s biniș — his coat — was new. Perhaps he had it made especially for this portrait, for which it is clear he prepared carefully. In his hand he holds his merchant’s license. He posed — imagine it — standing motionless, bundled up, composing his most important expression, one of gravity that could not be ignored. It is an oil portrait that shows us a brave man, almost a martyr.

Looking at him, you wonder what he wanted. Perhaps he only wished to immortalize the best moment of a life made of fabrics and buttons, or whatever it was he sold. And to be fair, he had achieved something: these clothes were not cheap. A coat like that cost around three hundred talers, and the ișlic could reach one hundred and twenty. It’s a pity we can’t see his fingers, which surely wore rings.

So yes, he was doing well. Perhaps this was the peak of his life and career.

In any case, what radiates from this portrait is an acute desire — one that surely contributed to the painting’s survival. I can easily imagine how his descendants revered it, how they kept the painting hanging in the salon.

The artist’s name has been lost. He took his money and that was that. Perhaps he laughed at his model’s stiffness. Surely he laughed. For him, it was a routine portrait. He didn’t even sign it. It wasn’t worth it. And yet today, Aredio Sochim’s face is preserved in a museum, while the painter’s name has sunk into the black waters of oblivion.

That day in 2003, when I laid eyes on him, I was overcome by an immense embarrassment. That was exactly how I looked in the photograph I had just picked up from Kodak — a face full of pretensions and hopes. In my eyes, too, you could see the effort I had made to look good.

I no longer felt like making my website. And for a long time after that, I couldn’t bring myself to be photographed at all. Because of Aredio, I don’t have a decent photo of myself. Even today, when I take a selfie, he appears over my shoulder — grave and ridiculous — by now a character in my debut novel.

Suțu Palace – a nineteenth-century aristocratic residence in Bucharest, today the Museum of the City of Bucharest.

İșlic – a traditional fur or wool hat worn by elite men in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Giubea / biniș – a long outer coat, often lined with fur, worn on formal occasions.

Anteriu – a long garment worn over the shirt, common in Ottoman-influenced dress.

Talers – silver coins widely used in Central and Eastern Europe.

Composer – early web-authoring software popular in the late 1990s and early 2000s.