I. Eleven years of age

He wandered the streets and the empty fields, strong and sure of himself. He wasn’t expecting anyone’s pity and no one cared about him. His mother was mostly gone, and he kept the house. He remembers her leaving in the morning, on her bike, aflush and wearing light-coloured dresses. He closed the door behind her, fixing it with a wire, and then bolted through Croitorului street, which led right behind the school.

In 4th grade... His friend was Raducu, poor Raducu! Dead in the Neajlov river, during a hot summer, when they were moving on to 7th grade. That was his luck, to live fast and short.

Ionel Greblă used to trail after them – a year younger, he can almost see him now, wearing a blue shirt, summer or winter, like an onion skin, waterproof, a type of top which his father had brought from Arad, or wherever he used to go thieving, as his dad is a bit of a gypsy on his side of the family. Even now old Greblă, when he comes out of the back room, old and dirty, he goes inside the shop, which is pretty much his son’s shop, and always palms whatever he can find, a cigarette, a coin forgotten on the counter, anything he lays eyes on, and snatches it with his black fingers, like a pack of dogs.

So, at 11 years old. Right on his birthday, on October 6th. He had started school and he remembers getting off around lunchtime. It was still sunny and warm, but an October warmth, distant and careful. Usually that is how he remembers all October days, though he does know for sure that there were years when October was waterlogged, or was so windy that it would curl his underwear. But in his memories, October is mostly sunny and clean like a soap bubble. He remembers the ploughed earth, the rusty river meadow and his shoes like drawn fish. It’s an old and embarrassing memory, stuck to the most hidden part of his skull. Maybe it wasn’t exactly October 6th, but it was definitely October.

He knew his mother was seeing all kinds of men, he could see her sometimes making anatomical joles with different individuals, who called from the pickup trucks – men going to work somewhere or coming from a football match – Tooori! Come and get it, Tori! – and she would pout her swollen, red mouth. He imagined she saw this type of men in the long days when she was gone from home. Sometimes she told him ‘be good, don’t do anything stupid and I am going to bring you something nice’ and he understood she was going to meet some guy and she was going to ask for something nice for him.

Often he hung around at Raducu’s, hoping to get to watch some TV. They were crazy about the wolf who cried ‘Nu zaietz, nu pagadi!’. They anxiously waited to see his grey body, swinging between the rows of apartment blocks, searching with his eyes for the poor rabbit.

Or they talked and weighed in on his mother’s comings and goings. ‘She’s a bit of a floozy, your mum’, Raducu would say, ’I saw her in whatever place, a guy was lifting her skirt, she’s got a set of legs on her, not bad’, and he laughed, they both laughed, because it seemed such a funny thing for her to be wanted by all men. Even now, on the downside of fifty, she still goes to the meadow or in the forest for a hookup – who cares what she does now? The only episode that hit him over his eyes was on that sunny October day, when he had seen her behind the thorny bushes blackened by the summer heat.

He had gone down to the riverbank. He walked slowly, lost in thoughts. First he saw her shoes. She had a pair of red shoes, with beige heels, from imitation wood, which seemed drawn on her small, white soles. He would have recognized them even in a mound of shoes, particularly because they were on her feet, who were also unmistakable. He dropped down, to the root of the blackberry bush. Through the gnarled thorny branches the red shoes could be seen, under a man’s legs. He had his overalls’ trousers down at his ankles, fallen in wavy rings, so you could see his tense hips, going up and down in an alert effort, as if he was in race for life or death.

Cristel also dropped on his belly, curious and at the same time in shock. The man was Țuțu the truck driver. And underneath was his mother, with her skirt pulled up to her waist. It was the first time he saw two people getting it on and, until he had time to think about his discovery, he saw that there were actually three people. When the truck driver lifted his head once, he saw her too. Tori had her eyes closed, and near her forehead kneeled Greblă, Ionel Greblă’s old man, he too with his trousers down, stroking it, with a face full of suffering. He had seen old dicks before, especially held in hands, but never one so red, as if it had spent three days in a barrel of crushed grapes. His mother’s face, partially covered by the truck driver’s iron arm, the black hands squeezing a piece of raw flesh and the twisted branches of the blackberry bush, plunged into the coppery chest of October, had entered violently deep in his marrow. Like a postcard stuck inside a mirror frame.

But this wasn’t all. He was lying there on his belly, slowly munching on a piece of walnut, found in his pocket, and he was staring, afraid that it will all come to an end, when suddenly Tutu turned onto his side. He rolled like a log, looked at the sky and then slowly got up. He forgot about the others, Tori and Greblă, as the trucker was sitting on his bottom and looking directly into his eyes. For a moment, Cristel believed he had not been spotted. Then Tutu broke into a long grin and winked at him. It was something done on impulse, maybe he was surprised to see him too, but even like this, without premeditation, it was a sign of complicity and at the same time of authority, that made him get up immediately and start running. He was happy to have seen such a hot scene. He was glad to have been alone. But at the same time he felt sad and humiliated like a piece of trash. He did not know what upset him more, which part of the episode, but certainly the trucker’s grin had dealt him a mortal blow. The squinted eye, the corner of his mouth sliding to the middle of the cheek and the black eyebrow, rising twice. He probably had recognized him. He knew he was Tori’s boy, it would have been impossible not to know it. And that is why he felt so humiliated, as if all the collective’s trucks had driven over him. And then there was Greblă, a man so ugly you would not be able to eat at the same table with him. Or at least that is how he saw him then. Recently back from jail, with his white spotted skull and weathered muzzle, as if somebody had used it to clean the floor, Greblă was the lowest of the low, who wouldn’t even fetch 5 bani.

He ran as far as he could, on the Neajlov bank, until he reached a small bay, with fine white sand, held in place only by the dried barberry plants. It was deserted, and on the other riverbank you could see some thorny bushes. He looked at them and realized that he would never forget this view, sucked dry of all life. Even the water flowed muddily, through the crumbling banks. Cristel sat down on the sand, gathered together his knees with his arms and started to cry. His tears fell and he felt extremely guilty for having let go, guiltier than if he would have committed a crime. But he was lucky no one was around to see him.

He wanted these two men to disappear from the face of the earth. To never meet them again. Especially Tutu.

But it wasn’t to be. They lived in a small village and every few days he saw the truck driving on the road, carrying corn, sunflower or beetroot, and from the cabin the driver’s head promptly would appear, with the eyebrow raised as if on command, whistling or looking straight at him, with the same taunting look. And thus, week after week, it became harder and harder to go out on the line of the village and face Tutu or Greblă. Even if he wasn’t certain that one had seen him, he assumed the driver had told him. They probably laughed at his expense. Greblă was a darkish man with a big nose, who always looked at him from one side, as if he were a package. Even now, when they meet in Ionel’s store, he looks at him with the same impish superiority, so you could see from far away he did not take him seriously at all.

For a few years he lingered on asphyxiated in the water of this event, a foul smelling mire. His mother had not been affected by it, she acted as if she did not know, but at one point, when he could not keep all that suffering inside, it turned out that Tori actually did not care, it did not seem important to her if he knew or not about her varied, daily adventures. ‘I’ve given you life, what else do you want? I could’ve shit by a fence and said you weren’t there!’

There wasn’t much you could talk about with her, so he left her be. But with the two men things got worse and worse. It got to the point that he would lower his head every time he spotted a truck gliding on the road, from far away, where the village began, when it looked like as small as matchbox. Sometimes the trucker would poke his head out through the window and asked him loudly ‘How’s your mother, is she home?’

Of course he did not answer, but said under his breath ‘Eat my ass’, but not too loud, so he could not be understood.

It was hard. Especially when Raducu was present too. Then all the pain and suffering rose up to roof of his mouth. He looked him in the eye and the tears would start. He could tell Raducu had noticed the trucker’s cruelty, but as Cristel kept quiet about it, he stopped pushing. Until the day before his death.

‘Why the hell don’t you tell me? What does this cocksucker got on you? Did he catch you stealing? Is he fucking your mother? Or maybe he wants us to break the windows on his truck?’

Three years had already passed since it happened, but he had not been able to talk about it even to his friend, who was a helpless witness to his inner turmoil.

The day before he drowned, they met Tutu again, and Cristel was gloomy. They were sitting on the bridge in front of the gate and Raducu kept begging him ‘tell me what this guy wants from you? You said you’d tell me!’

But he hadn’t, he had run home, and hid under the cherry plum tree thinking about it until nightfall. He had to tell him. Even more: he had to take revenge on the trucker and that tramp Greblă. He had made up his mind, steeled himself and felt confident he had to talk about it and he would have probably kept his word, if Raducu hadn’t died the next day.

It wasn’t until then that Cristel’s hate overflowed.

He was looking at his friend, lying in the coffin, ashen and lifeless, just the container in which his soul had been packaged, and he had a dark feeling that he had died to show him how insulted he had been by his pointless silence.

And then he had that horrific dream. One night he dreamt about Raducu. He was standing in the middle of the street and he was looking somehow from down low to up high towards his room. He had an enormous head and was saying in a thickened voice ‘Nu zaiet, nu pagadi!’. Cristel had pulled back, frightened. But Raducu smiled at him as if trying to say ‘what are you doing? Don’t you trust me? I’ve barely left and you’ve already thrown me on the rubbish heap?’

Feeling ashamed, he opened the door, waiting to see what he had to say. And Raducu had asked him calmly:

‘What wish do you want me to grant you?’

He could not believe it. It was exactly what he wanted to be asked, but at the same time he could not hope that his friend’s ghost could grant his wish.

‘Come on’, Raducu went on. And he did say, in the end:

‘I wish you could rid me of the trucker!’

‘I knew it!’ said the ghost, swaying his abnormally big head. ‘So, do you want me to take

him out?’

Yes, that was exactly what he wanted. To be wiped off the map.

‘Done! ‘ his dream friend answered him, and, because he wanted to leave as if he was in a hurry to fulfill the wish, he almost screamed:

‘And Greblă too!’

‘Greblă? Do you want me to kill him too?’

‘Not him... his dad, you know, I don’t want to see him for a while.’

‘How long for?’

‘Two years.’

A couple of days later after the terrible dream, Tutu the trucker died in a car accident, and

Greblă got caught stealing and was sentenced to two years in jail.

These events made him very confident. And when he met Florenta, he thought he could see Tutu in her. But a harmless, gentle and humble Tutu, exactly as he wanted him to be.

(trans Daniela & Mat Riain)

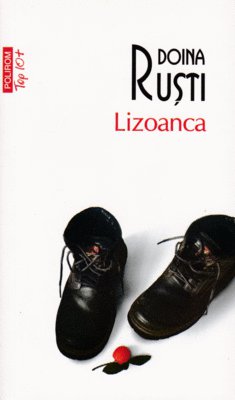

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/2919952.DoinaRuti