Lizoanca at the age of eleven is a shocking story, a story which, throughout its first chapters, recalls the ferocity of a writer like Agota Kristoff, although in the case of Doina Ruști it is inserted against an ultimately grotesque and even burlesque background. Perhaps it is not – certainly not – a coincidence that both Kristoff and Ruști come from the dismembered Eastern Europe.

Miguel Baquero, La tormenta en un vaso, December 16th, 2014

"It’s with great joy that I recommend the novel Lizoanca at the age of eleven by author Doina Rusti, to be granted the Romanian Academy Award for literature.The history of a teenager from a Romanian village, in our lifetime, the clear, memorable, vivid sketching of the features typical to her age, but also of the character that constantly oscillates between characteristic and pathological – a pathology rather determined by her time and environment! –, the vigour and richness of the "small" events that surround this being, who’s aggressive because of humans’ lack of understanding and kindness, in fact a sacrifice of time and history – they all add to the value of this book.

The certainty, the mastery of the portrayal, the precise and original description of the environment, the pursuit of a subtle crescendo of the epic, with the false air of keeping still, make Doina Rusti, in my opinion, a first-rate prose writer of current literature."

Nicolae Breban, upon granting the Romanian Academy’s Award

"As for the literary value of the novel, I think it is one of the most remarkable in current literature. The narrative intelligence, the fluidity of action, the perpetually surprising expressiveness of the text, the brevity, the poignancy of the characters, the precision of the distinguishing gestures within an episode (short and directly approached, without introductions, sometimes with barely sketched authorial reflections) and the way each short chapter fits into the whole are marks of a novelist with availability of means that could make her future novels, after The Ghost in the Mill and Lizoanca, become important literary events."

Gelu Ionescu, Târziu de fare, Cartea Românească Publishing House, 2012

Doina Ruști has abandoned the positive/negative character type of writing, has no moralizing impetus, does not aggravate the situations, does not even have a contrarian vehemence that condemns the media and the journalists. Lizoanca is a believable character. (…) There is another plan of writing involved, which gives strength to the fictional construction: Doina Ruști does not simply tell a story in the present tense. Each character has its own anamnesis, a placement of adult characters in the context of their own 11-year-old age. Each character is a representative of that age of opposites, when you are no longer a child, but you have not reached maturity either.

Ovidiu Șimonca – Observator cultural, no. 465, 2009

Lizoanca deserves a separate study that reveals the strength of the prose writer Doina Ruști, the employed solutions, always different, the ability to go from one technique to another, the ways to set up frames of excessive verisimilitude, of a credibility that places the novelesque discourse before the tendentious one and, above all, the skill with which she always assembles and dismantles the pieces of a sui-generis game that is the art of the novel.

Constantin Dram, Convorbiri literare, April, 2008

Doina Ruști is an excellent prose writer, of great talent and intuition, with a frugal style, humour and candour, sarcasm and affection towards her characters who are always lively, interesting, ambiguous, original, precisely as the author wants them to be.

Norman Manea, cover IV, ed. 2013

Since her debut in prose in 2004 with The Little Red Man, the word most often used in connection to her novels is vigour. With every new book (Zogru in 2007, The Ghost in the Mill in 2008, and now Lizoanca at the age of eleven), one could also notice a special combination of leitmotifs and fictional versatility, invariably leaving behind a remainder in the form of a distinctive (female) character, always in a defensive position, with all her thorns removed, adapted to withstand the wear and tear of a guerrilla battle with life, not necessarily from the victor’s stance. (...) One of Doina Ruști's critics noticed that all her characters are equally well defined, with an unusual poignancy.

Tania Radu – Revista 22, April 7th, 2009

Lizoanca drags after her a horrifying, agitated world, drained by alcoholism, depravity and social frustrations, of a vitality with deeply negative roots, even more frightening through its verisimilitude, through the appeal to something familiar of which we usually don't want to take note.

Tania Radu – Chenzine literare, Humanitas Publishing House, 2014

With Petrache Notaru we find ourselves in the first founding myth, even in a kind of cosmogony of sin: if the basis of any human society is the taboo of incest, this world that birthed Lizoanca was founded precisely on the overthrow of this taboo, under the confused protection of some diffuse divinities.

Vintila Mihăilescu – Dilema Veche, April 16th, 2009

I find admirable the way in which the author builds this novel around the age of 11, as a leitmotif. Each character, who in one way or another comes into contact with Lizoanca, from the inhabitants of Satu Nou to the journalist who is brought up on this subject, goes back in time, at the age of 11, as if touched by a magical wand. This way, Doina Ruști manages to weave her complicated web of connections, motivations, histories, which in the end make up a complex overall picture, comprised of several distinct stories. Of course, in the end, you also recognize Doina Ruști from her other books, by the ease of the narration and the obsession with the roots and ancestors.

Mihaela Spineanu – Dilemateca, June, 2009

Tortured physically and mentally by her father, Lizoanca revolts, she knows that she can earn her freedom by other means. In this novel, violence is not a simple representation, but an exceptionally rendered one, through a multitude of forms, placed at the bottom of existence. Lizoanca is involved in a series of actions that concern not a singular case, but the whole society.

Adina Mocanu – La Vulnerabilidad de las niñas en la transición postcomunista, vol. La infancia en femenino las niñas, Icaria Editorial, Barcelona, 2016

This book hurts because it's so real. It reminded me as a narrative and as a psychological game of Rebreanu's novels (even of Ion). The writer knows her characters well, describes them through memories and facts, and does not name their character traits until you see them for yourself by getting engrossed in the book. Doina Ruști writes very well, and this absolutely disturbing novel must remain well inscribed in Romanian literature. It's all fun and games until you come across a book that grabs you by the throat and throws on the ground. Reading is always a gratifying experience, but this is an authentic piece of literature that speaks precisely about the state of affairs of our country, even if it accomplishes it with an almost forbidden mastery. This book left me in pieces undeniably because of the truth it carries with it. It seems to me that it is one of the must-read books of contemporary Romanian literature. Don’t miss it! Both a challenging and easy read. Challenging because of the topic that tears you apart at any moment. Easy because it's so expertly written (which also pierces your heart). It seems to me that you need to have a lot of courage to be able to turn this subject into a novel (not a shocking biography, nor a graphically horrifying novel, perhaps seductive, but sensational, essentially a thriller). No. To take this heartbreaking topic and turn it into literature. This is what it means to make real literature.

Ramona Boldiszar, De vorbă cu sine, 2020

Extremely painful, uncomfortable writing, the essence of human hatred. We are witnessing the corruption of the entire society, burdened by a terrifying past, which has brought it down morally. It is definitely a pressing prose, which asks the reader for a truce. Ruști converts her novel into an angry movement, directed against depravity and moral decay. Beyond the documentary value, it is a novel of extraordinary literary qualities.

Antonio J. Ubero, La Opinion, 3.01.2015

Lizoanca’s dramatic plot is built on 13 symbolically linked stories, making up a second story within the novel, that of Petrache Notaru, the actual main character in my opinion. This type of story, meant to reshape the character’s essence, is frequent in Doina Ruști's work, and I would say that it also embodies a sort of imprint of her style. The stories share a narrative, fictional and highly compelling dimension.

Pompilia Chifu – Texte și discipline în dialog, Perspective comparatiste și comunicaționale, Universitaria Craiova Publishing House, 2019

Doina Rusti writes a novel with higher stakes than one would think after a hasty reading: it’s a novel about Evil. The banality of events and characters in Lizoanca at the age of eleven is related to a so-called "banality of evil". The book depicts a strong, solid realism, built with that self-confident pen of the "objective prose writer".

Bianca Burța Cernat – Revista 22, Bucureștiul cultural, Oct. 6th, 2009

The novel distinguishes itself by a singular narrative style, which details the present and past of the characters, bringing together the reminiscences of communism and a quality fiction.

Dulce Carpio, Letra S, 261, April, 2018, cultural supplement of the daily La Jornada, Mexico

Her predilection for investigating a raw rurality, the frankness and hardness of a speech not without empathy, grafted on a rich compositional imagination, are elements that make postmodern artifice enthusiasts wary. The author has all the credentials of a vocation novelist, with roots deeply embedded in the humus of the lower world, whose traditional landmarks were torn away by communism.

Doina Ruști's characters are strong and humanly believable, and the rural community, with its prominent and its run of the mill members, is just as acutely portrayed as the people from a rating-hungry media.

[Lizoanca at the age of eleven] is an intense, shocking and unusual narrative experience, which only a prose writer endowed with epic passion and inner strength could offer.

Paul Cernat – Revista 22, Bucureștiul cultural, no. 3 Nov., 2009

Doina Ruști's novel, Lizoanca at the age of eleven, which I translated last year for Orpheusz Kiado, was included in a list of the 10 best novels published in 2015 in Budapest, along with the books of well-known writers, such as Attila Bartis, Zoltán Danyi, György Dragomán or Noémi Kiss. The top was published in the daily newspaper Magyar Nemzet.

Szenkovics Enikő, Székelyföld 4/2016

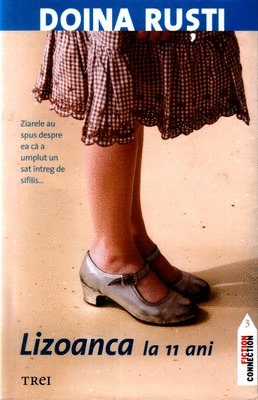

Doina Ruști's manifesto, translated into the novel Lizoanca, definitely left a mark. The book promised to be a shocking one just by looking at the cover, where the review succinctly described the subject, but I did not expect it to haunt me so much after reading it. To say I was shocked is an understatement, as this novel turned out to be so striking and equally grim that I was on the verge of giving up on it a couple of times. But my inner strength kept me going, and I went through the novel with a heavy heart.

Corina Moisei, Matricea Românească, 2017

Lizoanca at the age of eleven impresses through the kaleidoscope of destinies, through the colourful and picturesque, tragic or grotesque characters and charms through authenticity, because it does not shy from searching for the seed of fiction in the mundane, nourishing it until it bears fruit. The age of 11 is the binder that gives consistency and depth to the book, a high threshold between childhood and adolescence."

Elisabeta Lăsconi, Viața Românească, No. 7-8 / 2011

Even the smallest details are truthful in the novel Lizoanca at the age of eleven.

Magyar Nemzet, December 31st, 2015

Doina Ruști, with a gradual unfolding of the story, prolongs the pain and horror to unsuspected limits, bringing the causes to the surface. She managed to write about that dark and even invisible part of society, questioning many of its essential elements.

The mini-scenes which, at least in the first part, have an explanatory title, reiterating that of the novel (Greba, Petrache, Păduchioasa or Cristel – at the age of eleven) initially act in counterpoint, but along the way you realize that they fully reflect the community, the village, gradually expanding the story to the entire Romanian society, without a doubt, true for any part of the world. Doina Rusti's ability to interweave Eliza's story with the story of those who abuse her is entirely surprising. Surprising is also the ability to echo personal and social hypocrisy or the theme of violence, shocking from the first sentence, always visible in the novel and in a permanently erosive role. To this add the characters, built not so much through portraiture, as you would expect in a realistic novel, but rather through action and dialogue.

A pictorial story (through the perfect use of simile ("face wrinkled like dirty panties", "pretty like a cat barely asleep") and cinematic through action. And a story that speaks of the individual (the lives of the characters) and the community (rural society, state reality), about the past (communism) and the present (post-communism), about space (the development of Dudu – New Town) and its characteristics (relationships with neighbours) or, among other elements, the performance of the mass media.

In short, a novel that tackles almost every theme that surrounds and concerns the human being in its relationships and coexistence.

Ramón Acín, Turia, 115, 2015

Doina Ruști cultivates a prose strongly rooted in the cruelties of the real world, with an engaging plot, with a strong narrative, dialogic, discursive availability, aimed at reconstructing the image of a world in turmoil. Domestic violence, alcoholism, the challenges of the marginalized, the suburban way of life draw in like in a mixer adults and children alike.

Maria Șleahtițchi, Meridian Critic, no. 2/2015

Lizoanca – an innocent product of this brutalized and hardened world – is introduced as an aggressive and unruly wild animal that instinctively discovers, at the rougher school of life, what we pompously call "moral conscience".

Paul Cernat – Revista 22, Bucureștiul cultural, no. 3 Nov., 2009

It can be said that Doina Rusti was not interested in the scandal, but in the moral side of the story, asking herself why everyone is silent: how can an entire community become a participant to the prostitution of a child?

The development of the novel consists of fiction, myth and sociographic exigency. However, it is not only the event that shocks the reader, but also the perspective of the character.

Nagy-Horváth Bernadett, Ambrozia 2/2016

Lizoanca at the age of eleven is a novel akin to Camus' The Plague.

Gianluca Veneziani, Libero Quotidiano, Turin, 18.05.2013

The novel Lizoanca at the age of eleven describes the childhood of an eleven-year-old girl, Eliza Nițǎ, known as Lizoanca. The story focuses on the girl's life. Thus, Lizoanca abandons her parents because they treat her violently and she tries to find a father figure in one of her friends. The girl then assumes family behaviours without a role model to follow. Sexually, Lizoanca is latent. The novel illustrates Lizoanca's relationships with the people around her, as well as a series of predominantly affective transfers and projections.

Simona Reghintovschi & Mihai Botezatu – Psychoanalytic interpretation of the novel Lizoanca at the age of eleven), Osterreichish-Rumanischer Akademischer Verein, 2011

Lizoanca at the age of eleven is "one of the most inflammatory Romanian prose that has seen the light of day in the last decades. [...] Lizoanca does not consist of an accurate reflection of today's Romanian realities, nor is it based on a precise conception of the biblical ancestry of communal evil. Indeed, the text contains enough socio-political, mentality-related and religious references, thanks to which the landscape of the Romanian society of the last two decades takes shape – a society fundamentally corrupt, stained, flawed to the limit of the abominable, but mimicking, totally unconvincingly, either a purity of normative extraction, or an ignorance of socio-economically instrumented conduct.

Emanuela Ilie, Lizoanca and the imaginary of trauma in Doina Ruști. Worlds, histories, "symbolic combinations"), co-ord. Emanuela Ilie, ed. Vasiliana 98, 2022

Lizoanca is a shattering book, written in a refined and nuanced style.

Martina Freier, when the book was added to the collection of the National Library, Berlin, 2013

Lizoanca offers the reader a perspective on the current Romanian rural landscape, raising issues related to human rights and immigration policies in the European Union.

Claudiu Zeppel, Deutsch-Rumänische Hefte, Jahrgang XVII · Heft 1, 2014

Doina Ruști's book can be considered to be postmodern naturalism: it contains determinism, the impossibility of happiness. Man is the prisoner of his instincts and because of this he becomes vile, bestial, primitive. The plot of Lizoanca does not take place in an urban environment, as in most novels of Zola, the father of naturalism, but it depicts the same core premise. The members of the community are characterized by dreadful soul desolation, by hopelessness, decadence, depravity. (...) The general image of the novel is positive and convinces us that a good novel can indeed be written about such a theme.

Zsidó Ferenc, Székelyföld 4/2016

There's a kind of collective guilt there that minimizes individual guilt and makes you even understand or empathize with the most abhorrent characters. In this book no one is innocent and that is why nobody is punished. A generalized impunity, because everything, from the law to the crime, is mocked. Locally, but also centrally, as we see on the news every day.

Dollores Benezic – Dolo zice bine, 2022

The novel Lizoanca at the age of eleven depicts a story that is gradually connected to other events, bigger or smaller secrets of the community. An ancient ring, discovered in 1940, the love encounters of a summer in the 70s, some Russian cartoons, the gratuitous malice of a teenager, as well as other facts that happened at the end of the 80s – they all lead to one man: old man Petrache. There is almost no character who hasn't had at least one interaction with this man. And all these past events are very closely related to the exceptional story of Lizoanca."

Il Giornale Letterario, 18 12 2013

"A fascinating read that grips you from the very first pages and takes you straight to the heart of the story through fast and dense chapters and a diligent focus on the main characters. To this, we may add a compelling view of the protagonists’ psychology. Everything is described in an imaginative, lively language, inexhaustible in inventiveness and exciting, but at the same time concise, direct, very harsh on occasion, with that vigorous roughness, necessary and useful."

Mauro Barindi, at a workshop with the translators, Mogoșoaia, June, 2009; coordinated by Florin Bican

It was enough for me to start it and then I couldn't put it down. Lizoanca is a sad, harsh book. Initially, I read it out of curiosity. Then, because I became attached to Lizoanca, I felt terribly sorry for her. It's a must-read book from my point of view, every chapter makes you feel that you live in a country where there is no sex education, where parents think they solve everything by beating up their children and where things are never moving forward, regardless of generation. I was a bit shocked by the detachment of the narrative style, but I think that's what makes it such a necessary read – it doesn't tell you what's wrong, it simply shows you. This is certainly not my last encounter with Doina Rusti.

Andreea Chiuaru, Goodreads

"A novel as bad as it is good."

Dan C. Mihăilescu, Omul care aduce cartea, PROTV, 2009

fragment from the doctoral thesis

Although historically affiliated with the 2000 generation, Doina Ruști was trained under the canons of the eighties, which she renounced, hence the difficulty of fitting her in a literary direction, in a biological or creative generation, as she possesses a unique aesthetic formula and style, as several critics, including Dan C. Mihăilescu[2] and Cătălin Sturza[3], have noted.

Doina Ruști has created an epic architecture of great complexity, with thoughtful diegetic discontinuities, as the action builds gradually, with an obvious interest in new techniques, with postmodernist links of great finesse. In fact, she created a reputation as an atypical author from many points of view, and upon brief research of the texts that have been written about her work, we notice that the originality of style and epic resolutions take precedence.

A lot has been written about her novels, around 150 studies and chronicles, most of them overwhelmingly positive, which we must admit represents not only a performance, but also proof of a good reception of her work. Italy, Germany, Spain, England – these are but a few of the 15 countries in which she had her work translated, where her novels had a good distribution and a critical reception to match. A prestigious magazine, such as Turia, edited by the Instituto de Estudio Turolenses, dedicates a thorough analysis to her in the same issue in which another Romanian writer is praised: Mircea Cărtărescu. The exegesis refers exclusively to the novel Lizoanca at the age of eleven, translated into Spanish, and is signed by a well-known writer: Ramón Acín. Right from the start, he notes the literary value of the novel Lizoanca, the epic strength of the prose writer and the talent to create artistic tension: "with a gradual unfolding of the story, Doina Rusti prolongs the pain and horror to unsuspected limits, bringing their causes to the surface."[4] The exegete dwells further on the characters, emphasizing their value within the writing. And it's not simply about construction, it's about characterological subtleties. In the same vein, Antonio J. Ubero writes an extensive chronicle in a daily newspaper with a large circulation, such as La Opinion[5], focusing, in particular, on the "exceptional qualities" that make this novel good literature: "Doina Ruști turns the novel in a general call to action, furious against the decay of ethical values that must govern any evolved society. Beyond its enormous documentary value, this novel reveals extraordinary literary qualities."[6] Antonio J. Ubero's arguments are epic and stylistic. He comments on various scenes, and makes references to the strong message of the book. In Mexico as well, Lizoanca was favoured with an empathetic reception. "The novel distinguishes itself by a singular narrative style, bringing together the reminiscences of communism and quality fiction," writes La Jornada,[7] Mexico City's top daily.

The originality of her writing is also highlighted in reviews of other novels. Along the same lines, Leonardo Sanhueza writes in a magazine from Santiago de Chile[8] about the parabolic layer of the novel Zogru, seeing in it particular meanings, which the Romanian exegesis do not highlight: "it is about a singular book [Zogru]" which examines the history and meaning of "belonging to a territory."

In Italy, Zogru is perceived by its organic side and rather as an escape from myth. Marco Dotti writes in the daily Il Manifesto that Zogru "accesses that temporality of fantasy which, in essence, is nothing but a return of a demon to humanity, an unfortunate connection with the earth[9]", and Roberto Merlo[10] believes that the originality of the text comes from the way it combines various aesthetic categories that support the fantasy register, without falling into the trap of repetition. The novel raised many debates. In Bulgaria, Bojidar Kuncev[11] sees in it a Cioranian writing, through the type of tragedy approached in the novel, an idea that none of the Romanian exegetes noticed, but which is also found in a chronicle from the daily newspaper Il Mercurio,[12] from Santiago de Chile. In it, Pedro Gandolfo, an exacting critic from Santiago, emphasizes, in a consistent review, the tragic vein of the book, seeing in this story a parable of existentialist alienation: "what predominates in this wonderful story [Zogru] is the trace of the terrible solitudes of a human spirit without love."

In this chapter on originality, we must also include the construction of the denouement, not infrequently noting the "unexpected ending", like in this chronicle of The Little Red Man, published in Stato Quotidiano.[13]

Another aspect related to Doina Ruști's work is its visually expressive capacity. "A pictorial story (through the perfect use of simile: ("face crumpled like dirty panties", "hands like carpet beaters", "beautiful like a sleeping cat", "a summer like a jar of jelly", etc.) and a cinematic one", says Ramón Acín[14] about Lizoanca, and La Stampa reinforces this idea, talking about the expressive plasticity in The Little Red Man.[15] In the same sense, Pedro Gandolfo compares Zogru to Chagall's paintings, considering them well-defined and of valuable visual metaphoricity[16]: "Full of humour in some scenes, in others tragic and ferocious, sometimes fantastical and bright, like a Chagall painting..."

The cinematic unfolding of the plot creates the impression of an undoubted reality in Doina Ruști's novels, as the daily Magyar Nemzet[17] notes: "Even the smallest details are lifelike in the novel Lizoanca".

Literary criticism often focuses on a reliable message, with certain social implications. Zürcher Zeitung, commenting on The Ghost in the Mill, sees in this novel a kind of artistic synthesis of communist experiences[18]. But most often invoked are the social reverberations in Lizoanca. Ramon Acin states that "Doina Rusti managed to write about that dark and even invisible part of society, questioning many of its essential elements.[19]", and Zeppel believes that Lizoanca poses problems related to human rights and immigration policies in the European Union[20]. Likewise, Zsidó Ferenc[21] and Nagy-Horváth Bernadett[22] talk about the pronounced moral side of the same novel. And Gianluca Veneziani makes an interesting comparison between Camus' The Plague and Lizoanca in the daily newspaper Il Libero[23].

Perhaps somewhat more unusual are the references to the type of fantasy cultivated in some of her works, which Romanian criticism hardly ever mentions. "The Little Red Man, in its Italian version, is seen as a dystopia and compared to works by Dave Eggers, Tommaso Pincio or Gary Shteyngart.", according to Noemi Cuffia[24]. And placing the novel The Ghost in the Mill in the neo-Gothic style is a new direction. Listed in The Ashgate Encyclopaedia of Literary Cinematic Monsters[25] by Jeffry Andrew Weinstock, Doina Ruști's novel is presented in a new light, which also entails a different kind of reception. The same idea is extensively analysed and argued in a study published in English by Raluca Andreescu[26]. It includes aesthetic arguments, dealing methodically with the "faces" of the ghost, as hypostases of fear and individual complexes that dominate a village. The unusual type of fantasy is also noted by Alyse Mgdrichian, in a chronicle to The Book of Perilous Dishes.[27]

Synthesizing these exegeses, which are not few, we find that, in the view of foreign critics, Doina Ruști's writings are characterized by an obvious originality, by a type of specific truthfulness, often supported by striking and unusual expressiveness, by lexical inventiveness.

Much more numerous, the Romanian critical texts dedicated to Doina Ruști are difficult to manage. Overwhelmingly, these are positive reviews or chronicles. Many important critical voices try either to place her in the landscape of post-Twentieth-century prose, or to identify the structural or semantic marks that display the undoubted particularity of her writing. Dan C. Mihăilescu classifies her as a member of the post-Ceaușescu era[28], because her debut was a non-fictional[29] work in 1997, and her first novel appeared in 2004 (The Little Red Man), during the 2000’s generation’s rise. Although her age can be placed at the end of the 80s, by the date of her editorial debut she remains linked to the 2000s.

There is a system of reference, perhaps more emphasized in Romanian criticism than in foreign criticism, an acute need for analysis that often evokes Lovinescian synchronism. The large number of writers and works invoked in support of this analytical genre gives both the measure of the exegete's culture and that of the prose writer's receptivity towards universality. Some of Doina Ruști's exegetes venture that her fantasy prose is closer to that of Marquez[30], an association that appears in several chronicles and which is rejected by Mihaela Ursa, in favour of a reference to Rushdie: "Rather than the Marquez model, the present novel [The Ghost in the Mill] activates the model of Salman Rushdie in Shame, where an infernal, apocalyptic beast is born and feeds on the fundamental imbalance of a community[31]." Sometimes the referrals are even more distant. Commenting on Zogru, Luminița Corneanu conjectures that "One of the most persistent impressions after reading the book is something of the vitality and freshness in A Midsummer Night's Dream". Others think of Bulgakov: "The procedure of the descent of the miraculous into everyday life reminds, through its humorous effects, primarily of Bulgakov, Ovidiu Verdeș[32] believes. Constantin Dram[33] follows the same idea.

Critical notes lean towards reference fiction. Dana Sala compares Baricco's Silk and Doina Ruști's Phanariot Manuscript[34], Dan C Mihăilescu says that The Book of Perilous Dishes is "a stylistic jubilation, a vital literature, like Suskind's Perfume up to a certain point and Eugene Vodolazkin’s Laurus to another, furthermore[35]"...

In other chronicles, it is said that the prose writer "also sketches a sui-generis mythology of the city of Bucharest, thus joining the series of those fascinated by Bucharest, from Mircea Eliade to Mircea Cărtărescu[36]."

The Ghost in the Mill (2008, 2017) remains the novel which established her. Paul Cernat[37] states about this novel that it is written "by a strong and original prose writer", and it is "one of the most convincing and expressive fictions about domestic communism published in the last decade". It is a laudatory statement, which many other critics make. Paul Cernat wrote about many of Doina Ruști's works, considering that she "writes well, expressively and 'virile', with an accuracy, fluency and casualness, able to simultaneously control multiple registers – imposing herself through the force of the narrative, well tightened in the straps of a substantial composition. Recovering the "need for the Story", the prose writer associates it, justifiably, with the need to recover our historical memory. Paul Cernat is also the most careful exegete of Doina Ruști, not missing any detail. One of his observations refers to the epic mechanism through which the real event goes through the stages of its fictional becoming, or, as he explains it, in Doina Ruști's work the naked fact goes through spectacular metamorphoses, without, however, altering the informative core. The originality of the prose writer lies in the way in which she possesses the rare art of placing the message in a memorable and unusual context[38]. Few of her exegetes have noticed this inclination, and among them, Dan C. Mihăilescu says it most bluntly: "The Ghost in the Mill is a fictional novel, along the lines of an autobiography, in which magical realism and everyday realism intertwine[39]."

The originality of the epic approach, a trait meticulously praised in international exegeses, is also emphasized in numerous local chronicles, signed by Bianca Burța-Cernat, Daniel Cristea Enache, Alex Ștefănescu, Tania Radu, Cristina Balinte, Alina Purcaru and many others. Mircea Muthu, commenting on The Phanariot Manuscript, finds that the novel, among other things, brings as a novelty a kind of "historical grammar[40]". The remark refers to the lexically supported layer of national history. A more general remark, related to the same quality, is made by Tudorel Urian: "The historical novel The Phanariot Manuscript details the extent of the talent of one of the very important authors of recent years[41]. Modest, talented, always original, discreet, removed from the spotlight of worldly life, Doina Ruști naturally became a first-rate author in the library of Romanian prose writers today." In the same vein, Nicolae Breban (upon offering the Academy’s Award[42]) praises, among other things, the "exact and original description of the environment" in Lizoanca. And Adriana Bittel writes about an "original formula[43]", and from Doris Mironescu's perspective, originality comes from the profound way in which Doina Rusti not only freed herself from postmodernist clichés, but gained a unique vision[44].

The key word in relation to Doina Ruști's writings is originality, most of the time with exact reference to the subject or the character. Moreover, it is not difficult to notice that from one novel to another, she approaches themes that are as unusual as they are afterwards eagerly pursued, because what no one has noticed yet is that Doina Ruști creates trends, has the ability to leave behind epigones. As Luminița Marcu, Liviu Antonesei or Mircea Mihăieș noted at the beginning, she mixes fiction and realistic epic, in a formula that is neither magical realism, nor Bulgakovian satire. "Intelligence, including artistry, was of great use to the author in choosing the formula and, above all, in covering it in the text! A novel [The Little Red Man] that you read with the pleasure of reading a detective novel, but with actual aesthetic stakes." states Liviu Antonesei[45], and Mihăieș remarks "the pleasure of creating imaginary worlds, that is, realities that you can touch with your hand[46]."

Each novel brings compositional novelties. None of the characters in Romanian literature resemble Zogru, The Ghost in the Mill has an unusual structure, and Lizoanca starts from a real, metaphorized case.

Next, we need to emphasize her ability to construct, almost unanimously noted. Doina Ruști's novels have a solid epic foundation, a realistic subject and observations. In this sense, Bianca Burța-Cernat also lauds the author in a reference article with the suggestive title: Rehabilitation of realistic illusion[47]. The analysis is careful and well-argued: "Doina Ruști has a gift when it comes to building, the ability to create fiction with stakes and an overflowing imagination. (…) If I were asked to recommend certain characters, pages or scenes from this second part of the novel The Ghost in the Mill, I wouldn't know where to start, because almost every aspect here is remarkable. "

In the same sense, Daniel Cristea Enache[48] places Doina Ruști "in the elite of prose[49]." Cristina Balinte[50] also talks about the well-built epic." Doris Mironescu agrees with this opinion: "Her talent is about construction, characters and situations that not only convince, but give you the feeling of presence. The imagined scenes are compelling, and their cascading sequence overwhelms[51]". In contribution to this vision, Mihai Iovănel notes: "The core of the novel is, among the three parts, the second part, The Windmill: it is slightly longer than 200 pages and it’s exceptional. In this compressed space-time sequence, the great qualities of the author are best revealed: the construction and ability to suggest the texture of humanity[52]."

Some critics have attributed the clarity of construction to the many techniques of portrayal. For example, the novelist Ioan Groșan states that Doina Rusti uses "a science of portraiture[53]," and Tania Radu observes the impeccable construction of the characters: "One of Doina Rusti's critics noticed that all her characters are defined equally well, with an unusual poignancy. The hall of fame in Lizoanca at the age of eleven is no exception[54]." Moreover, this remark is found in many chronicles, and it must be said, here, that the characters gain consistency in the context, most of the time a deeply human one built on traditional foundations. Vintilă Mihăilescu best formulates the idea: "With Petrache Notaru we find ourselves in the first founding myth, even in a kind of cosmogony of sin: if the basis of any human society is the taboo of incest, this world that birthed Lizoanca was founded precisely on the overthrow of this taboo, under the confused protection of some diffuse divinities.[55]."

Profound, with reference to both sociological and mythical facts, the anthropological approach of Vintilă Mihăilescu somewhat widens the space of reception into the area of the epic construction and justifies the impression of strong realism, which Bianca Burța Cernat tackles: Lizoanca "is of a strong realism, solid, built with that self-confident pen of the "objective prose writer[56]". Technically, the construction arouses the interest of criticism. A famous philologist like Gelu Ionescu (the exegete of Eugen Ionesco's work and the unmistakable voice of Europa Liberă) delivers an applied analysis of the novel Lizoanca, insisting on the epic intelligence and composition, which in Doina Ruști's novels is impeccable[57].

After reading the enormous critical material, what is left behind is a talented writer with an indisputable body of work. I noticed that both foreign and Romanian exegeses insist on style, literary qualities, but above all, the originality of her novels. Many of the annotators of her work appreciated the complexity of her fictional worlds, with their historical settings or epic developments, in a never-ending story, but also the veracity supported by a solid construction.

[1] Study partially taken from the doctoral thesis

[2] Dan C. Mihailescu, Omul care aduce cartea, Pro TV, April 15th, 2010

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M4S8DVDEQxQ

[3] * Cătălin Sturza, Observator cultural, April 16th, 2010*

[4] TURIA. Revista Cultural no. 115, 2015, p. 234

[5] La Opinion, 03.01.2015

[6] Antonio J. Ubero, La Opinión, 03.01.2015

[7] April 5th, 2018

[8] Leonardo Sanhueza, Las Últimas Noticias, Santiago de Chile, May 7th, 2018

[9] accesses that temporality of fantasy which, in essence, is nothing but a return of a demon to humanity, an unfortunate connection with the earth" (t.n.), in Il Manifesto, May 15th, 2011. The text can also be found here: https://www.micciacorta.it/2011/05/i-demoni-della-romania/

[10] Quaderni di studi.., no. 5, 2010, Edizioni dell’Orso, Torino, p. 134

[11] About fate in Zogru, Literaturni Balkani, Sofia, 1/2009

[12] August 19th, 2018

[13] “A substantial novel with a dash of mystery that, by the end, perfectly achieves its goal of leaving the reader enthralled.” Roberta Paraggio, in Stato Quotidiano July 3-5th, 2012. It can also be found here:

https://www.statoquotidiano.it/29/09/2012/macondo-la-citta-dei-libri-89/101608/

[14] ibidem, p. 325

[15] “The explosion of original, poignant expressions is entirely overwhelming.” (t.n), Alessandra Iadicicco, La Stampa, nr. 1815, May 12th, 2012

[16] ibidem

[17] December 31st, 2015

[18] “Doina Ruști's book showcases a wide range of literary skills, which give the measure of posterity in the Romanian history of the 20th century” (t.n.), Markus Bauer, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zürch, 4.01.2018

[19] ibidem, “Doina Ruști managed to write about that dark and even invisible part of society, questioning many of its essential elements.” (t.n)

[20] Deutsch-Rumänische Hefte*, Jahrgang XVII · Heft 1 · Sommer 2014

[21] in Székelyföld 4/2016

[22] Ambroozia 2/2016

[23] May 18th, 2013

[24] Tazzina di caffè, May, 2016: “On the border between health and illness, between real and fantastic, between mysticism and the everyday, this book explores, in a fresh style, a dystopian vision, reminding me of The Circle by Dave Eggers, Panorama by Tommaso Pincio and Super Sad True Love Story by Shteyngart.”

[25] Routedge, New York, 2016

[26] vol . Studies in Gothic Fiction, Zittaw Press, 2011

[27] Shelf Media Group, April, 2022, Los Angeles

[28] vol I-III, Polirom Publishing House, 2005-2007

[29] Dictionary of symbols from Eliade's work

[30] Horia Gârbea, Ziua literară, January 22nd, 2005

[31] Apostrof, no. 11, 2008

[32] Cuvântul, June 2006

[33] Convorbiri literare, February (110), 2005

[34] Weaving a Narrative from Metamorphoses in Alessandro Baricco`s Seta and Doina Ruști's Phanariot Manuscript – ALLRO, Volume 22, 2015

[35] https://www.facebook.com/LibrariaHumanitasDeLaCismigiu/videos/1452430624777965/?pnref=story

[36] Gabriela Gheorghișor, Dilemateca, May, 2010

[37] Paul Cernat, Comunismul românesc în moara realismului magic, in „Revista 22”, Bucureștiul cultural, no. 2, of December 2008, https://revista22.ro/bucurestiul-cultural/bucurestiul-cultural-nr-152008-i

[38] ibidem

[39] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tKyeX9uWL6o&feature=youtu.be

[40] Apostrof no. 4 (311), April, 2016

[41] Viața Românească no. November 11th, 2015

[42] See the holograph text in the Annex

[43] Formula AS, no. 854, 21.02/2009

[44] Suplimentul de cultură, May 9-15th, 2009

[45] Liviu Antonesei – Timpul, March, 2005

[46] Cotidianul, August 13-14th, 2005, p. 17

[47] Observator cultural, no. 459, of 29. 01.2009

[48] Daniel Cristea Enache in Timpuri noi, Cartea Românească Publishing House, 2009

[49] Timpuri noi, Cartea Românească Publishing House, 2009, p. 177

[50] Cultura, April 6th, 2006

[51] Suplimentul de cultură, May 9-15th, 2009

[52] Cultura, 29.01.2009, no. 4

[53] Observator cultural no. 792, October 2nd, 2015

[54] Revista 22, April 7th, 2009

[55] Dilema Veche, April 16th, 2009

[56] Revista 22, Bucureștiul cultural, Oct 6th, 2009

[57] Apostrof, no. 10/2009

See also Critical Reception

and [BIBLIOGRAPHY]

Pompilia Costineanu Chifu: What was written about Doina Ruști